The woman artist appears quickly to have grasped the fact that she cannot maintain an isolated and merely selfish point of view, since the interests of all are indissolubly bound together.

Edith Hinchley, ‘Why we want the Vote: the woman artist’ in The Vote, 12 August 1911

Edith Hinchley, humanist and member of the West London Ethical Society, was an artist, suffragist, and broadcaster. Her formative experiences as an art student in the celebrated institutions of 1890s Kensington may have influenced her involvement in the suffrage movement. She wrote about challenging the teaching environment for women students and the challenges for women artists in a field traditionally dominated by men. Through her writing and activities, her belief in a society with shared values of mutual respect and participation is evident. She was also a member of the Fabian Society.

The artist, and especially the woman artist, is often supposed to live entirely in a world of beautiful dreams, whereas the actual facts of existence press as hardly upon her, or even more so, than upon most men.

Edith Hinchley, ‘Why we want the Vote: the woman artist’ in The Vote, 12 August 1911

Edith Mary Mason was born on 21 January 1870 to John and Frances Mason in Park Walk, Chelsea. Edith was one of four sisters. John Mason was a master gardener and later had a floristry business. After her father’s death, Edith and her sisters lived at Park Walk with their mother who continued the business. In the 1891 census Edith is an ‘Art Student’. She attended the South Kensington School of Art and graduated as the school was reinventing itself as the Royal College of Art.

In 1890 Edith, interested in genealogy and heraldry, worked on an illustrated family tree for a friend in the aristocratic Lucy family. Comprised of 500 heraldic shields painted on deerskin, it is known as the ‘Lucy Deerskin’. It is held a Charlecote Park (National Trust) in Warwickshire. In 1896 Edith was elected a member of the Royal Society of Miniature Painters.

By 1901 Edith, an ‘Artist Painter’, lived with her family at 15 Fawcett Street, Chelsea along with two boarders, one of whom was chemical engineer John William Hinchley. Two years later, Edith and John were married. In 1904 John went to work in Siam (now Thailand) as an assayist (ensuring the quality of a metal) and as head of that country’s Royal Mint. Edith accompanied him and continued her painting there, returning to London in 1907.

Edith became active in the suffrage movement. In August 1911 she wrote an article for The Vote, the newspaper of the Women’s Freedom League, on the challenges for working women artists, and the injustices and inequalities in art schools. At South Kensington, female students had to sit at the back of a classroom, separated by chaperones from the male students at the front. Edith was partially deaf so this would have affected her considerably. She wrote:

At South Kensington the scholarships originally allotted to women for the same qualifications as for men were only granted for half the period. The big prizes, travelling scholarships and the diploma of the College were therefore denied to women who could not do the same work as the men in half the time!

In 1922, Edith became a member of the Society of Women Artists. In 1924, at her own suggestion, she produced a series of historical portraits of ‘worthy’ historical figures, along with a brief biography of each, for a calendar published by the London Electric Railways Company. Among them were Sir Christopher Wren, William Hogarth, Elizabeth Fry, Charles Dickens, and Florence Nightingale. According to the Western Daily Press:

Mrs Hinchley’s aim was to foster the spirit of citizenship through the medium or art, and it is one that should be widely adopted, for every town and city in the kingdom has its own history of honourable men and women whose names should ever be remembered by, and whose portraits should be familiar to, their townsfolk of the present and future generations, in schools and in their own homes as well as in public buildings.

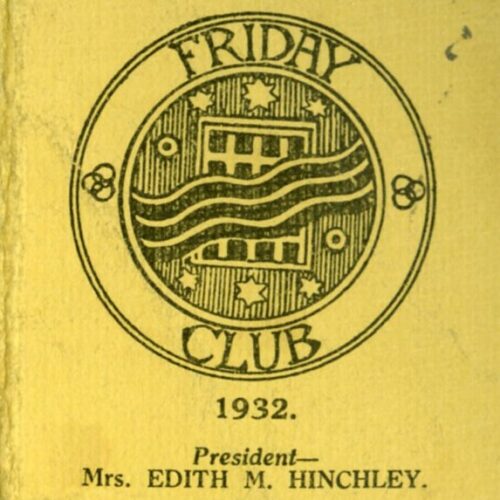

A humanist with an eye on social reform, Edith Hinchley was a contributor many times over to the funds of the Rationalist Press Association, and a member of the Fabian Society. She was also an active part of the Ethical movement, especially through her involvement with the West London Ethical Society and its secular Ethical Church. With her husband, she took an active role in the social life of the Society, acting as President of its Friday Club, which organised lectures and rambles, and contributing artistically—for example through a richly illustrated copy of the Ethical Church’s marriage ceremony.

John Hinchley died in 1931 and as the founder of the Institute of Chemical Engineers and a Professor at Imperial College, London, the tributes to him are considerable. Edith wrote a personal memoir about her life with her husband for private circulation. She continued working, also broadcasting on BBC radio short slots on the care of miniatures and frames. She died tragically on the night of 16 October 1940 when her marital home in 55 Redcliffe Road was completely destroyed during a night time bombing raid. Her body remained undiscovered for five days. She is remembered on a wall plaque at Golders Green Crematorium, erected by Imperial College and Edith following her husband’s death.

Edith Hinchley was one of a number of creative, campaigning women drawn to the reformist spirit of the early humanist movement. Like them, we can glimpse her presence through archival records of the societies she engaged with, and form an idea of the ideals which motivated her—like equality, artistry, community, and education.

Society of Heraldic Arts Newsletter 2015

‘Why We Want the Vote – The Woman Artist’ by Edith M Mason-Hinchley in The Vote, 12 August 1911

Western Daily Press, 12 January 1924

Edith M. Hinchley, John William Hinchley Chemical Engineer – A Memoir (1934)

Edith Mary Hinchley | ArtUK

By Liz Goodacre

In my experience he was the kindest of men, far too modest about his own contributions and always prepared to […]

I think that one of the most hopeful signs at the present day, and one for which this Movement can […]

Can there be a more important human condition than dignity? Without it, we are bitter, downtrodden, unheard, humiliated, embarrassed and […]

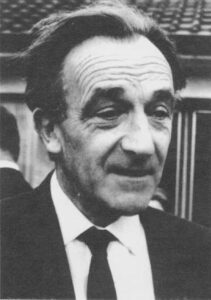

Good writing excites me, and makes life worth living. Harold Pinter Harold Pinter was one of the 20th century’s most […]