Only victory will put an end to it all. But meantime let no one say: ‘We are not responsible.’ We are responsible if a single man, woman or child perishes whom we could and should have saved.

Eleanor Rathbone, speech to House of Commons, 19 May 1943

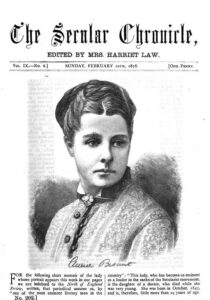

Eleanor Rathbone was a feminist and a humanitarian whose humanist values led her to devote her life to supporting the poor, the disadvantaged, and the voiceless. As a leading feminist she promoted a ‘new feminism’ concerned not just with achieving equality between the sexes, but also with addressing women’s needs as women. And as a politician her profound compassion led her to become known as ‘the MP for refugees’.

Family Endowment involves something much greater than a scheme of child welfare, or a device of wage distribution… it offers a hope, not dependent for achievement on a revolution or a scientific miracle but realizable here and now, of making attainable by every family, even the lowest on the industrial ladder, the material means for healthy living.

Eleanor Rathbone, The Disinherited Family: A Plea for Direct Provision for the Costs of Child Maintenance through Family Allowances (1927)

Eleanor Florence Rathbone was born into a long line of social reformers whose family motto was ‘What ought to be done, can be done’. Her father was the eminent Liverpool merchant, philanthropist, and Liberal MP William Rathbone VI and her mother was Emily Acheson Lyle. Rathbone was educated largely at home, but was tutored in Latin and Greek by the feminist Janet Case before going up to Somerville College to read classics and philosophy. These studies led her to reject both metaphysics and religious dogma in favour of a ‘rational scepticism’, while her involvement in social work convinced her that concern for others was the foundation of ethics and that religion was thus not needed as a guide to life.

While still at university Rathbone helped her father investigate the circumstances of casual labour in the Liverpool docks, an enquiry which revealed the devastating impact that docker’s erratic wages had on their wives and children. In 1903 Rathbone began work with the Liverpool Victoria Women’s Settlement and, together with Elizabeth Macadam, greatly increased the extent of its benevolent activities. Rathbone also launched the Liverpool Women’s Citizens’ Association to educate women in citizenship, an initiative which was widely copied across the country.

Rathbone joined the Liverpool Women’s Suffrage Society shortly after leaving university and soon became a member of the executive committee of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. As such, identifying and seizing the opportunity, she ensured that in 1918 women over 30 received a local government vote as well as a parliamentary vote. The following year she succeeded Millicent Garrett Fawcett as NUWSS President and led a renamed and repurposed organisation in successful campaigns for universal women’s suffrage, equal guardianship of children, divorce law reform, and widow’s pensions.

At last we can stop looking at all our problems through men’s eyes and discussing them in men’s phraseology. We can demand what we want for women, not because it is what men have got, but because it is what women need to fulfil the potentialities of their own natures and to adjust themselves to the circumstances of their own lives.

Eleanor Rathbone, speech at a conference of the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship, 1925

Having seen the beneficial results for soldiers’ wives and children of wartime separation allowances, Rathbone argued in The Disinherited Family (1924) for family allowances paid directly to mothers in proportion to the number of their children. A major advance in the field of distributive economics, her book convinced William Beveridge to make universal children’s allowances a key component of his welfare state proposals. Rathbone, who was elected to parliament in 1929 as an Independent MP, took every opportunity to promote her policy and lived to see it implemented by the Family Allowances Act 1945.

Meanwhile, Rathbone campaigned alongside the Duchess of Atholl against female genital mutilation in Kenya, and against child marriage in India, East Africa, and Palestine. She also worked for the representation of women as both electors and legislators in the proposed post-independence Indian constitution, helping to secure a special wife’s franchise and reserved women’s seats.

In April 1933 Rathbone warned parliament of the threat to peace posed by Hitler’s seizure of power in Germany. She denounced the government’s policy of appeasement, and called for re-armament and a national government led by Winston Churchill. As the international situation worsened, Rathbone combined once more with the Duchess of Atholl to rescue 4,000 Basque children from the fighting in Spain. She then pressed the government to take in Jewish and other refugees from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. And following the outbreak of war, Rathbone worked to secure the release of interned ‘enemy aliens’, many of whom were Jewish or anti-Nazi refugees from Germany and Austria.

In 1942, when news of the Holocaust reached Britain, Rathbone urged the government to save Jewish children in Vichy France who were at risk of removal to Germany, and to promise a British entry visa to any Jew who managed to reach a neutral country. Tragically, the government failed to act, but Rathbone’s humanist values held firm and, rejecting all thoughts of revenge, she helped the publisher Victor Gollancz organise shipments of food to Germany during the dreadful post-war winter.

Eleanor Rathbone was one of the most influential feminist leaders of the interwar period. As a parliamentarian, Rathbone’s success derived both from her independence of mind and her determination, but also from her pragmatism and willingness to compromise. Remarkably for a backbencher, she was responsible not only for the Family Allowances Act but also for other significant legislation in the field of family law. As her obituarist observed ‘No parliamentary career has been more useful and fruitful’. Perhaps more significantly, a close colleague described her as ‘the most selfless humanitarian I have ever known’: a profoundly humanist legacy.

Mary D. Stocks, Eleanor Rathbone: A Biography (1949)

Bob Holman, Champions for Children: The Lives of Modern Child Care Pioneers (2001)

Susan Pedersen, Eleanor Rathbone and the Politics of Conscience (2004)

Susan Cohen, Rescue the Perishing: Eleanor Rathbone and the Refugees (2010)

By Paul Ewans

The object of Secularism is the promotion of human happiness in this world… [The Secularist] believes the surest way of […]

Humanists International was formed in 1952 as the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU): a federation of the American Ethical […]

Humanism is an attitude to life that has solidly practical implications… it implies a commitment to helping run the community […]

You must abolish your oppression yourselves. Do not depend for its abolition upon God or superman. Your salvation lies in […]