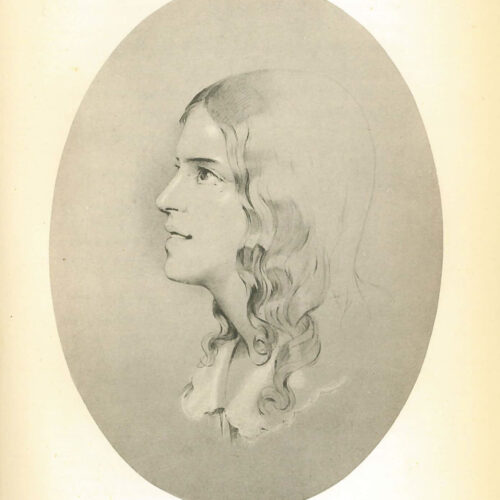

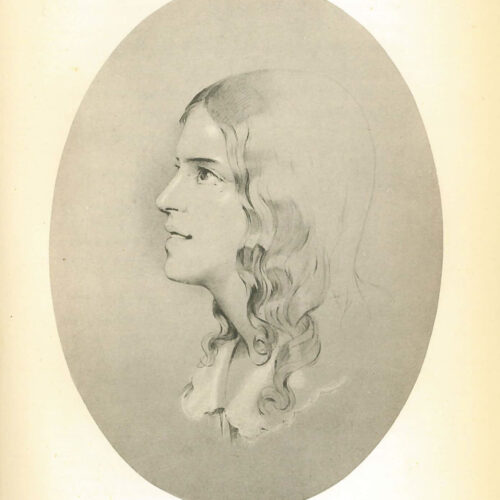

Eliza Flower was a composer, a radical, and a significant influence on William Johnson Fox and the progressive values of South Place Religious Society (now Conway Hall). A gifted musician, she did much to raise the priority of music at South Place, composing numerous songs and staging popular performances. Along with her sister, Sarah Flower Adams, Eliza was part of an era of developing humanism at South Place, arising from the questioning of traditional religious ideas and a wider interest in social justice and reform.

For me, I never had another feeling than entire admiration for your music — entire admiration — I put it apart from all other English music I know, and fully believe in it as the music we all waited for.

Robert Browning, Letter to Eliza Flower, 1845

Eliza Flower was born on 19 April 1803, the eldest daughter of radical, Unitarian printer Benjamin Flower, and his wife Eliza (née Gould), who was of similarly radical leanings to her husband. Benjamin Flower had been imprisoned in Newgate in 1799 on accusations of libelling Bishop Richard Watson, and had met Eliza Gould while there. The couple married on his release, in 1800, and had two daughters: Eliza and Sarah. The girls’ mother died in 1810, and they were raised by their father.

When the family moved to London in 1820, the girls were quickly adopted into a radical, cultured circle, which included Harriet Martineau, Robert Browning, and John Stuart Mill. At the centre of this was William Johnson Fox, the minister of the South Place Chapel (today Conway Hall Ethical Society), which was described by leading Unitarian James Martineau as a ‘free-thinking and free-living clique’. Fox became the sisters’ guardian on the death of Benjamin Flower in 1829 and Eliza in particular became very close to him, assisting him in literary work and – following Fox’s separation from his wife – helping to establish a ‘radical salon’ in the semi-rural Craven Hill Gardens, in Bayswater, London.

Throughout the 1830s, Eliza was active in the musical life of South Place, composing, performing, and working closely with Collet Dobson Collet, its musical director. She set words written by her sister to music (most famously Nearer, my God, to thee), and wrote Hymns and Anthems, a musical service for South Place. Eliza also composed music for the funeral service of Indian social reformer Rammohun Roy, who was a noted influence on William Johnson Fox and at South Place. South Place itself continued to act as a melting pot of progressive, liberal ideas, on religion, politics, art, and education. The Monthly Repository, edited by Fox with the assistance of Eliza, acted as a mouthpiece for many of these ideas, transforming steadily from a Unitarian periodical to a radical, secular journal.

Eliza Flower died near Brighton on 12 December 1846, suffering from consumption. She was buried in the family grave at Foster Street Burial Ground in Harlow, Essex, a nonconformist cemetery. Eliza and the circle she moved in were distinctly unorthodox, and a key generation in shepherding South Place’s increasingly humanist outlook. Her memorial service there took place on 20 December, led by William Johnson Fox.

Eliza Flower was central to the ‘free-thinking and free-living’ South Place, which cultivated religious freedom, creative expression, and progressive social and political values. Through music, and in her contributions to William Johnson Fox’s literary work, Flower helped to voice – and shape – these South Place values, taking inspiration from secular art and literature in a way that remained typical as the congregation grew ever more humanist. The Flower sisters are also a reminder of the significant role played by women in the social, cultural, and intellectual life of the ethical societies and their precursors, engaged just as much in religious questioning and unorthodoxy of all kinds as their male counterparts.

Conservation… draws us towards not only a scientific but a philosophical and historical approach to the problems of the earth […]

‘Separate Development? Out of the closet, into the ghetto’ was a talk given by writer and activist Maureen Duffy on […]

Humanism is… a tradition of thought and feeling combined with social action which stems from classical times and which has […]

The old teaching was that we must worship not truth, beauty and goodness, but their source, and that their source […]