… purely human and natural ethics, and not theology, was the source of this pioneer woman’s enthusiasm for justice, even before an Ethical Society had been conceived.

Zona Vallance, ‘The Women’s Suffrage Convention’ in Ethics, 1903

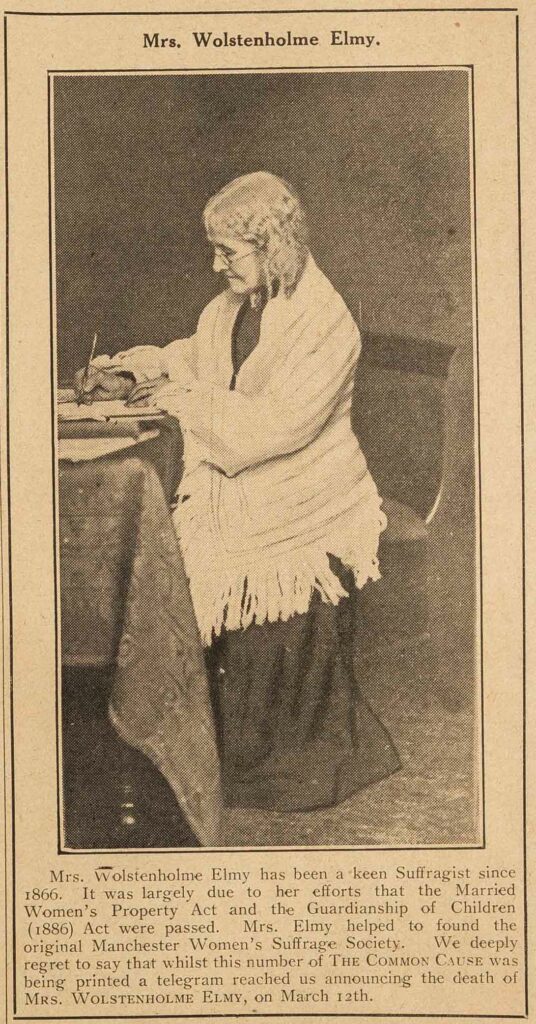

Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy was a remarkable and pioneering activist for women’s rights, whose legacy was unfairly overshadowed by her unconventional attitudes towards sex, and by her atheism. Wolstenholme Elmy’s tireless campaigning efforts helped to usher in significant pieces of legislation, including The Married Women’s Property Act of 1882, the Guardianship of Infants Act of 1886, and the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts in the same year. She was the first woman to speak publicly about marital rape, and spent over five decades championing humane, progressive reform. In 1903 fellow feminist and freethinker Zona Vallance took to the pages of Ethics to highlight Wolstenholme Elmy’s prodigious significance, as well as her entirely humanist motivations.

Elizabeth Wolstenholme was born on 30 November 1833, the daughter of a Methodist minister. Her mother, Elizabeth (née Clarke), died soon after her birth, and her father by the time Elizabeth was 14. Despite a limited formal education, Wolstenholme was a noted intellect and autodidact. She took over the running of a girls’ school near Worsley, becoming its headmistress, viewing education as a worthwhile, and vital, vocation. Later establishing her own school, Moody Hall, in Cheshire, she remained an educator until January 1873, by which time her increasing religious scepticism left Wolstenholme unable to teach the required Christian curriculum.

Wolstenholme has been involved in efforts for social reform from the 1860s. In the early part of the decade, she established the Manchester Board of Schoolmistresses in service of women’s education and employment, and actively supported the North of England Council for the Promotion of the Education of Women. In 1865, she joined the Kensington Society, devoted to expanding the rights of women. These acts signalled the beginning of a decades-long career of activism. Significantly, Wolstenholme Elmy did not attribute her ceaseless impulse to social improvement to any childhood religion, but to an innate empathy with other human beings: a deeply felt sympathy with the sufferings of others. As Maureen Wright has written, Wolstenholme is best ‘understood viewed through a lens of feminist humanitarianism – as the advocate of an ethic of active compassion for all human life.’

Over the following decades, Wolstenholme was a tireless worker for women’s rights, in matters of political, economic, educational, and bodily autonomy. Her formation of a women’s suffrage committee in Manchester (supported by, among others, Richard Pankhurst) helped to usher in what would become a nationwide network of suffrage societies. In 1867, she became the Honorary Secretary of the Married Women’s Property Committee, which fought to abolish ‘coverture’, a legal doctrine which made a married woman’s property that of her husband. In 1869, Wolstenholme became aware of the Contagious Diseases Acts, passed in the previous years to address an epidemic of sexually transmitted infections among the armed forces. The Acts disproportionately affected women, particularly the poor, by enabling the forced examination, detention, and punishment of those defined as prostitutes. With Josephine Butler, Wolstenholme embarked on a campaign for their repeal, forming the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts. In 1884, the acts were suspended, and in 1886, finally repealed. During the 1870s, she was an active figure in both the Committee for Amending the Law in Points Injurious to Women, and the Vigilance Association for the Defence of Personal Rights, both of which expanded their remit beyond women’s suffrage to address all aspects of sex inequality.

Also during the 1870s, Wolstenholme entered a free union with fellow freethinker, and Vice President of the National Secular Society, Ben Elmy. Both disapproved of conventional marriage, not least in its subjugation of the legal rights of women, and it was only outside pressure – concerned with the reputation of the women’s movement – which led them to formally marry on 12 October 1874. Their son was born a few months later. Wolstenholme Elmy was now only strengthened in her resolve to challenge legal injustice, continuing to champion the rights of married women. She played a leading role in securing the passage of the 1882 Married Women’s Property Act (as well as its precursor in 1870), and the Guardianship of Infants Act of 1886, which extended women’s custodial rights over their children.

In 1889, Wolstenholme Elmy became Secretary of the Women’s Franchise League, which advocated the inclusion of married women in demands for suffrage, as well divorce and marriage law reforms. In 1892, she established the Women’s Emancipation Union. A longtime advocate of the honest education of children, it was under the auspices of the Women’s Emancipation Union that Ben Elmy’s Baby Buds, and The Human Flower: A Simple Statement of the Physiology of Birth and the Relations of the Sexes were published: books on botany which served also as sex education handbooks.

During the early 1900s, Wolstenholme Elmy expressed her explicit support for the burgeoning Ethical movement. She wrote a fortnightly column for Stanton Coit’s Ethical World, and was acknowledged by Zona Vallance – the Union of Ethical Societies’ inaugural Secretary – as an active supporter of the movement’s campaigns. Lauding the National Convention for the Defence of the Civic Rights of Women, which took place in Holborn Town Hall in October 1903, Vallance wrote:

The original author of the enterprise was a lady whom the women of England ought to bless every morning when they rise. I allude to Mrs. Wolstenholme Elmy, whose self-sacrificing life and labours have been a more or less hidden mainspring of the women’s movement during more than thirty years. Through every kind of obstacle she has worked all those years for fourteen and fifteen hours a day; and, tiny woman as she is, has played the part of a giant and of one of the generals of the women’s movement in destroying the vile C. D. Acts, in carrying the Married Women’s Property Act through, and also the act which gave mothers the few rights they now enjoy in regard to the custody and control of their own children. Besides this, our readers will be interested to know that purely human and natural ethics, and not theology, was the source of this pioneer woman’s enthusiasm for justice, even before an Ethical Society had been conceived; and that she joined the Moral Instruction Movement before the League had ceased to be a mere Conference; and has given her services gratis in seeking financial support for this paper and in promoting its spread.

Zona Vallance, ‘The Women’s Suffrage Convention’ in Ethics, Vol. VI. No. 43, October 24 1903

Wolstenholme Elmy’s final decades were marred by the failure of Ben Elmy’s silk mill, which strained the couple’s finances. A ‘grateful fund’ was established by her friends and supporters, providing her with a modest annuity. She remained active in the causes which had animated her life, an early supporter of the Women’s Social and Political Union (established in 1903), and the author in 1907 of a pamphlet titled Women’s Franchise: the Need of the Hour. The following year, well into her 70s, she marched at the head of a WSPU procession to Hyde Park. Wolstenholme Elmy lived to see the enactment of limited women’s suffrage but died, on 12 March 1918, before she could cast her own parliamentary vote.

Emmeline Pankhurst described Wolstenholme Elmy as the ‘brains behind the suffragette movement’, and Maureen Wright has since helped to cement her legacy as ‘the most significant British feminist theorist of her generation’. Wolstenholme Elmy helped to shape arguments for the central role of women as citizens, deserving of full citizen status, which subsequent feminist writers – including Mary Gilliland Husband, Zona Vallance, and Laura Morgan-Browne – made full use of. As Wright has written:

Such an imagining of women’s contribution to the state’s future changed forever the grounds on which the definition of a citizen was constructed and brought all women, regardless of class, race, ethnicity or religion within its remit.

Wolstenholme Elmy rejected arbitrary distinctions between individuals, and eschewed party politics, seeking instead to unite all people on the grounds of their common humanity. Her convictions were fundamentally humanist in origin and scope, and she played a major role – as Vallance makes clear – in paving the way for those humanist activists who came after her. Wolstenholme Elmy’s philosophy is eloquently summed up by Maureen Wright, who notes:

She wrote that work to seek an egalitarian world should transcend any dogmatic belief system – either of religion or of party politics – and that society should seek only that path to the world’s salvation which put at its heart the honouring of human life.

… in broad terms, with our lecturers we attempt to define our intellectual standpoint; with our music we try to […]

The attempt to create communities where men and women alike share the full stature of humanity is an attempt to […]

The British Museum is a museum of human history and culture in London. Its collections include objects of humanist heritage […]

Ludovic Kennedy was a writer, journalist, and broadcaster, known for his investigations into miscarriages of justice. A human rights campaigner, he […]