Oh what a tissue of inconsistencies are the dogmas in which we have been reared!

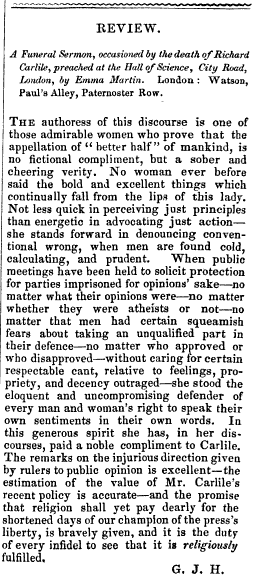

Emma Martin, God’s Gifts and Man’s duties (1843)

Emma Martin was a devoted and outspoken proponent of atheism and Owenism, turning a rhetorical talent and Biblical knowledge gained from earlier Christian evangelism to the causes of socialism, women’s rights, and freedom of belief. Martin advanced these principles first as a lecturer, and later as a midwife, consistently demonstrating a devotion to humankind underpinned by a deeply felt feminism and an undeniably humanist philosophy.

Religion, with an upward glancing eye, asks what there is above. Philosophy looks around her and seeks to make a happy home of earth.

Emma Martin, A Few Reasons for Renouncing Christianity and Professing Infidel Opinions (1844)

Born in Bristol to religious parents, Emma Martin (née Bullock) was in her early years fervently devout. At 17, she joined the strict Particular Baptists, distributing evangelical tracts and marrying, in 1831, fellow Baptist Isaac Luther Martin. Despite producing three daughters, it was an unhappy union; her husband being one ‘whose company it was a humiliation to endure’.

The daughter of tradespeople, her upbringing had allowed her relative freedom when it came to study. With this came increasing doubts about her faith, and the role of religion in society. Historian Barbara Taylor has described

a growing sense of the insupportable contradiction between what she demanded of her faith, both emotionally and intellectually, and the bleak offerings of orthodox religion.

Despondent in her marriage, and by now delivering lectures on the social status of women, Martin attended her first Owenite socialist meeting in 1839. She was moved on hearing beliefs so closely allied to her own, but disturbed by their rejection of Christianity and the Bible. Inviting adherents to publicly debate this, Martin became acknowledged as a formidable opponent. As time wore on, however, her religious beliefs began to weaken. Martin increasingly recognised the impossibility of improving the status of women without better education and employment prospects, as well as the barriers to both erected on grounds of religion. By the winter of 1839, Martin had left behind her husband and church, living instead as ‘a declared freethinker’. She would later write:

This change in my sentiments was the result of calm investigation. It was only by a long and laborious process that my mind was emancipated from the thraldom of religion. I speak of its thraldom not because it placed limits on the passions, for it possessed charms for me on that account, which it has lost only because I see a nobler way by which a purer morality can be secured; but I apply this term to religion because it fetters reason, because it would subjugate instead of improve the understanding.

Emma Martin, Letter to the Rev. J.W. Massie, Oct. 6, 1844

With this transformative confidence in the social and moral possibilities of Owenism, Martin rapidly became one of the movement’s most famous woman speakers, drawing crowds of up to 3000. For Martin, and others like her, the rationalist, socialist, and humanist philosophies of Owenism offered a sense of radical possibility, including for the absolute equality of women. They also proposed a system of good works and cooperation loosed from concepts of divine reward or punishment, and so from the repressive elements of organised religion. As Taylor has written, rather than combining ‘charitable professions with conservative politics’ as the Baptists had, Owenism offered a community of people ‘for whom charitable fellow-feeling was part of a wider system of radical belief.’

The Owenites proposed a revision of morality entirely separate from any god or creed, shaped instead by a love of humanity and a desire for social improvement. The movement’s periodical, The New Moral World, proclaimed ‘the sciences of human nature and of society, and, as a corollary, the science by which a superior character may be imparted to every child brought into existence’ as the intellectual foundations of a new vision. This would allow the masses to disregard ‘all sectarian creeds and superstitious mummeries’, encouraging instead ‘the constant practice of promoting the happiness of every man, woman and child, and regarding with a merciful disposition everything that has life.’

Martin spoke, debated, agitated and wrote in favour of social reform and gender equality, becoming ‘notorious for her knockabout style of free-thought polemic and… hostility to conventional Christian views on women and marriage’ (Taylor). Armed with an exacting knowledge of the Bible, she became a fierce critic of religion. Her challenge was not merely to its spokesmen and interpreters, but to the truth of the Bible itself. She revelled in pointing out its inconsistencies, and refuted its messages on feminist grounds. Similarly to others, like freethinking lecturer Eliza Sharples (1803–1852), Martin challenged the doctrine of original sin, and argued equity for women. Her brand of atheism, viewed as especially provocative, landed Martin in court more than once, and drew criticism from within her own party as well as from without.

In addition to these conflicts, Martin had to cope with raising her daughters alone, on only the salary afforded to her from the Owenite central board. Eventually, she withdrew from lecturing, though remained committed to the service of others. Retraining as a midwife, she lived with her partner Joshua Hopkins, who adopted her name. Though rejected from hospital positions on account of her atheism, she practised privately from 1847 until her death at the age of just 39 in 1851. In the course of these years, she also advocated for women’s right to be trained in obstetrics and gynaecology, and to have access to factual information about their own bodies and health. For this cause, she continued to lecture and to write, setting these rights, once more, in direct opposition to any religious indoctrination that might challenge them:

I would rather give my daughters a set of physiological and obstetric books for their perusal than allow them to read the Levitical Law.

Emma Martin, ‘A Review and a Prospect’, The Reasoner, Vol. 4, No. 91 (1848)

Emma Martin died in 1851 at her home in Finchley Common, succumbing to tuberculosis. At the time of her death, she was reading George Eliot’s translation of Strauss’ Life of Jesus. George Jacob Holyoake requested subscriptions for the purchase of a headstone for her grave in Highgate, to which many (including Harriet Martineau) contributed.

To step out of the current of opinion at the call of truth… and accept the accidental and tardy appreciation of the few, in lieu of the ready regard of millions, is a sacrifice that few are equal to; but it is one which converts life into a poem.

George Jacob Holyoake, eulogising Emma Martin in 1851

Recalling Emma Martin after her death, George Jacob Holyoake, her longtime friend and supporter, wrote that ‘if there be in the end a Judge who looks with an equal eye on all, he will not fail to discern the motive and pardon the means.’ Martin, though, did not die fearing such a judge, her godless creed of love for humanity animating her belief in equality and female advancement to the end.

Martin’s humanist philosophy, and her arguments for secularism and social equality, anticipated those of the ethical societies by half a century. Like them, she argued for the inadequacy of religion to explain the world or to define morality, placing the responsibility for humankind’s improvement squarely in the hands of human beings, and in this world, not any other. Later humanist writers, like Zona Vallance, echoed Martin in arguing that science and reason proved Biblical notions of male supremacy entirely false, and necessitated an entirely new way of understanding and organising the world. For both women, humanism encompassed a feminist approach to society, offering an enlightened morality and a path to rational reform.

In February 2023, following a successful campaign by Bristol Humanists, a plaque was unveiled for Emma Martin at 9 Bridewell Street, Bristol, close to her former home in the city.

Barbara Taylor, Eve and the New Jerusalem: Socialism and Feminism in the Nineteenth Century (1983)

Laura Schwartz, Infidel Feminism: secularism, religion and women’s emancipation, England 1830-1914 (2013)

Emma Martin | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Elhanan Winchester was the first minister of the dissenting congregation that eventually became the humanist South Place Ethical Society in […]

It is necessary to the happiness of man that he be mentally faithful to himself. Infidelity does not consist in […]

The British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS) began as the Birmingham Pregnancy Advisory Service, created to provide access to safe, legal, […]

… purely human and natural ethics, and not theology, was the source of this pioneer woman’s enthusiasm for justice, even […]