There is nothing to fear from Gods, nothing awaiting us in death; good can be obtained, evil fortune can be endured.

The Fourfold Epicurean Prescription, Philodemus (c. 110 – 35 BCE)

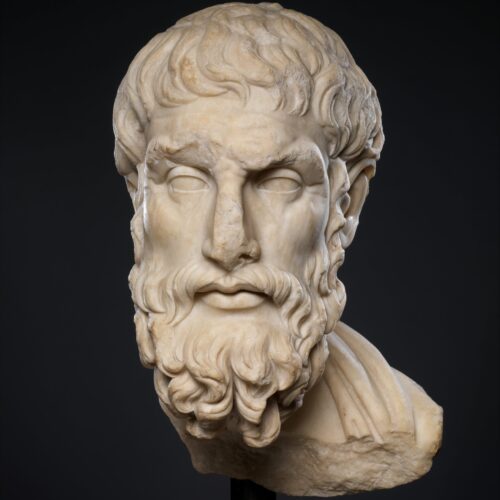

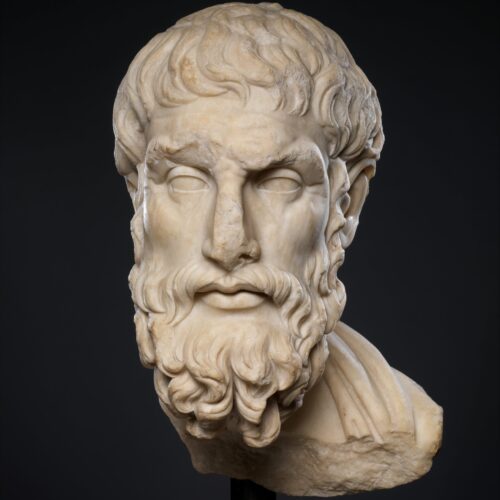

The Greek philosopher Epicurus founded a school of philosophy based on the pursuit of happiness through natural means: removing the fear of punishment from gods, and emphasising instead pleasure, friendship, and fulfilment in the one life we know – values embodied by humanists today. Sometimes associated with decadence and hedonism, in fact, Epicurus and his followers emphasised a simple life, living communally and sharing responsibilities and rewards. Subsequent writers and thinkers, like Cicero and Lucretius, chronicled and developed Epicurean thought, and in turn influenced those who rediscovered classical philosophy during the Renaissance.

Epicurus was born in 341 BCE on the island of Samos, and went to Athens at 18, probably to attend the Academy (founded by Plato). Leaving Athens in 321, Epicurus went to Colophon, where he studied philosophy under Nausiphanes (a follower of Democritus). Epicurus taught for several years elsewhere – including on the island of Lesbos – before returning to Athens in about 306 and founding, upon purchase of a garden, a school of philosophy. The Philosophy of the Garden became an alternative name for Epicureanism, and the Epicurean school of thought one of the Ancient World’s most enduring. He was the first philosopher to admit women to an organised school.

Epicurean philosophy centred on happiness as the ultimate goal of human life, a goal Epicurus viewed as being hampered by prevailing beliefs in an afterlife and the fear of punishment after death. Epicurus posited instead that nothing can be known of the gods; that they would have no interest in human affairs anyway; and that death was not to be feared. His philosophy was based in an empirical understanding of knowledge, arguing that only what can be experienced and observed is knowable. Science could help to dispel superstitions and allay fears arising from a lack of understanding, so a faith in this – rather than in myth or magical thinking – could work towards a genuinely fulfilling life. Aspirations towards immortality (or the fear of it) could only result in anxiety; by contrast, the surety of death was a levelling experience, and one that gave meaning to life. Epicurus himself died in Athens in 270 BCE, at the age of 70 or 71.

Epicurus’ philosophy was expounded by his followers and inheritors of Epicurean tradition, extending its reach far beyond his own lifetime. Although most of Epicurus’ own works are lost, Diogenes Laertius’ Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers gave biographical details and preserved some of Epicurus’ own writings, also noting that in spite of malicious (and false) rumours about Epicurus’ over-indulgence in physical pleasures, he lived a simple life and was ‘unsurpassed’ in his ‘goodwill to all men’, gathering innumerable friends and admirers. In the first century BCE, Lucretius and Philodemus further promulgated Epicurean thought. Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius’ De rerum natura (On the nature of things) was enormously influential in bringing Epicurean ideas to a Roman audience, and its rediscovery in the 13th century had a significant impact on Enlightenment thinkers.

Of all the things which wisdom acquires to produce the blessedness of the complete life, far the greatest is the possession of friendship.

Principal Doctrines, Epicurus

In its focus on living well with others, striving for happiness in this life, and dispensing with concerns about gods or the afterlife, Epicureanism is deeply humanist. Epicurus himself was known as a profoundly humane individual, and Diogenes Laertius records that in his will he appointed a successor, and made provisions for the children of his friends: an ‘afterlife’ distinctly Epicurean, and humanist.

There is no hope but us. There is no mercy but us. There is no justice. There is just us… […]

She was greatly gifted, and through her genial nature made friends everywhere. To the last she was an enthusiastic Rationalist, […]

Emilie Holyoake-Marsh, daughter of George Jacob Holyoake, was an activist for worker’s rights and women’s suffrage; an advocate of co-operation, […]

And how can woman be expected to co-operate unless she knows why she ought to be virtuous? Unless freedom strengthens […]