And how can woman be expected to co-operate unless she knows why she ought to be virtuous? Unless freedom strengthens her reason till she comprehend her duty, and see in what manner it is connected with her real good?

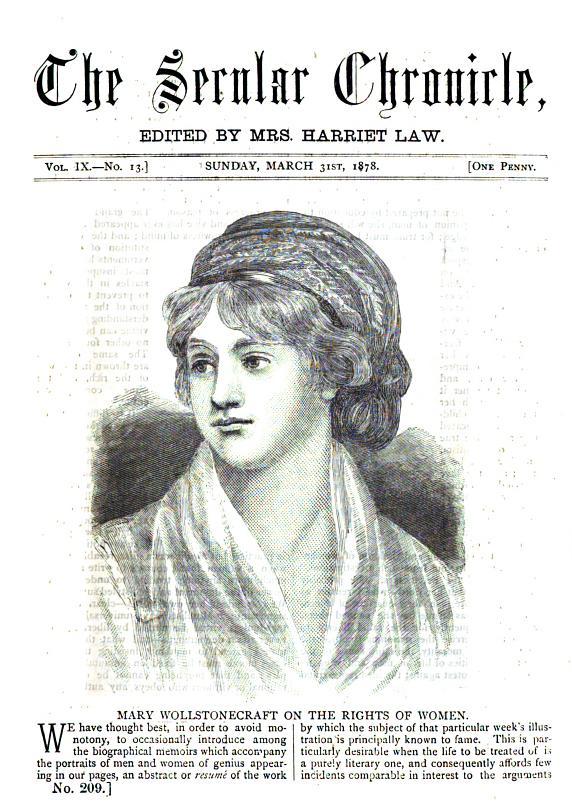

Mary Wollstonecraft

Writer, teacher, philosopher, and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft was a prominent freethinker and notable influence on generations who came after her. The wife of William Godwin, the pair lived a self-determined and – for its time – radical existence, both producing works of lasting significance to humanists today. Best known for her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), Wollstonecraft was a passionate advocate of women’s rights, a bold and original thinker, and an example of how outspoken and unorthodox women could be pilloried for their acts and ideas.

Mary Wollstonecraft was born in Spitalfields, London on 27 April 1759. Though previous generations of the family had enjoyed relatively prosperity, her father, Edward Wollstonecraft, proved inept at maintaining it, and the family’s fortunes suffered increasingly throughout Mary’s childhood. Her only formal education was some years at a day school in Yorkshire, at which she learned to read and write. All else, including an impressive array of languages, was self taught. The frustration with educational inequality between the sexes, to be excoriated in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, had its roots in this early hardship – her elder brother, and the favoured child, Ned, receiving the only ‘gentleman’s education’ among the Wollstonecraft children.

The family’s finances undermined Wollstonecraft’s marriageability, and the limited professional prospects for women (teaching, needlecraft, lady’s companion) were all tried and rejected. Writing, though, provided an avenue for self-support, as well as the opportunity to try out and establish her own ideas. Settling in London to pursue this new career, Wollstonecraft produced translations from French and German, read widely, and wrote reviews. She was also introduced to such radical freethinkers as Thomas Paine and William Godwin.

In 1790, enraged by Edmund Burke’s conservative critique of the French Revolution, Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Men, attacking the aristocracy and defending republicanism. The work made her instantly well-known, though her 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Woman secured her reputation today as a groundbreaking work in the tradition of women’s rights.

In it, Wollstonecraft applied ardent feminism to her calls for freedom, reason, and education, regardless of sex. It was, she argued, by ‘considering the moral and civil interest of mankind’ that a love of it could develop, ‘from which an orderly train of virtues spring’. Education was central to this, and vital for women: ‘but the education and situation of woman, at present, shuts her out from such investigations.’ Drawing, like many women writers before and since, on the responsibilities of motherhood in passing these values down through generations, A Vindication was a rallying cry for equality, rooted in civic duty and mutual responsibility in society.

Moralists have universally agreed that unless virtue be nursed by liberty, it can never attain due strength – and what they say of man I extend to mankind, insisting… that the being cannot be considered rational or virtuous who obeys any authority but that of reason.

In her emphasis on freedom and reason as the touchstones for virtue, Wollstonecraft’s ideas resonate strongly with the humanist approach today.

In May 1794, Wollstonecraft gave birth to a daughter, Fanny, conceived with American writer and adventurer Gilbert Imlay. In the same year, she published An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution, which attempted to present a carefully constructed history of the events in France and their impact on a range of people.

Wollstonecraft returned from France to London in 1795, rejoining a circle of writers and radicals. Among these was William Godwin, with whom she embarked on a passionate love affair and partnership of equals. Despite Godwin’s own misgivings about the institution of marriage, when Wollstonecraft became pregnant the pair decided to marry in order to avoid scandal. The couple moved to Somers Town, London, where they lived separately, retaining their independence but maintaining a close and happy relationship.

Wollstonecraft gave birth on 30 August 1797 to Mary, the child who would go on to achieve fame as the writer of Frankenstein. Tragically, Wollstonecraft contracted septicaemia, and died on 10 September. She was buried in Old St Pancras Churchyard.

To a friend, Godwin wrote:

I firmly believe there does not exist her equal in the world. I know from experience we were formed to make each other happy. I have not the least expectation that I can now ever know happiness again.

Writing in The Secular Chronicle nearly a century after Wollstonecraft’s Vindication was published, secularist Harriet Law noted her predecessor’s bravery in writing as she did, when she did:

then it was a disagreeable novelty when a woman found courage to write anything; much more anything tending to undermine the power of the dominant and self-styled superior sex.

Freethinkers George Eliot, Barbara Bodichon, and Virginia Woolf were among the later feminists who championed Wollstonecraft against accusations of social and sexual impropriety, which lingered even 100 years on. Wollstonecraft remains an inspiring figure in the history of freethought and feminism, representing a devotion to values of freedom, reason, and equality, which remain at the heart of humanism today.

No one who came in contact with her failed to recognize in her fearlessness, honesty for the sake of honesty […]

Alice Woods was an educationist and headteacher; a member of the Hampstead Ethical Institute, and a proponent of moral education. […]

The Open University was founded in 1969 with the ambition of providing access to higher education for people who had […]

Kensal Green, opened in 1833, was London’s first commercial cemetery, and the originator of the city’s ‘Magnificent Seven’. These suburban […]