Ernestine Mills, an enamelist, and her husband Dr. Herbert Henry Mills were both active members of the Ethical movement, and champions of progressive social causes. Ernestine was an accomplished artist and an advocate of female suffrage, creating many works in support of the cause. Herbert Henry Mills served on the advisory board for the 1911 National Insurance Act, helping to ensure medical care for the poor, and often treating those in need for free. Both were motivated by humanist values and progressive ideals, and offer a window into the diverse and inspiring figures who propelled the early organised humanist movement.

Ernestine Mills was born in Hastings on 6 January 1871 to Major Thomas Evans Bell, a retired army general, and his wife Emily (née Magnus), an actress and graduate of the Royal Academy of Music. Both were freethinkers, radicals, and suffragists, as well as being supporters of George Jacob Holyoake and the socialist Owenite movement. Throughout Ernestine’s first decade, her parents served alongside Richard Marsden Pankhurst on the Central Committee of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage.

Ernestine’s first schooling was at home with a governess, and later attendance at Notting Hill High School for Girls was marred by ‘ill health’ – possibly that of her father, who died in 1887. Her mother, Emily Evans Bell died six years later in 1893, her obituary printed in Holyoake’s The Reasoner. Ernestine, aged 21, was left to the guardianship of Professor William Ayrton, a physicist and family friend. Ayrton’s wife Hertha – a former pupil of his – was an engineer, physicist, inventor, and suffragette, as well as a close friend of Marie Curie.

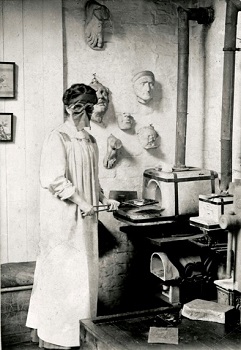

Instructed in drawing from childhood by the artist Frederic Shields, a friend of the Evans Bell family, Ernestine attended South Kensington School of Art, before being awarded a place at the Slade School. At the same time, she undertook night classes in silversmithing and enamelling at Finsbury Technical College. Ernestine Evans Bell married Dr. Herbert Henry Mills in Kensington, in 1898. Both were members of the Fabian Society, and the West London Ethical Society. Their daughter Hermia was born in 1902, and went on to be a doctor.

After his death, Ernestine edited The Life and Letters of Frederic Shields, published in 1912, in which she recalled her first impressions of him as ‘a fascinating but rather alarming giant.’ In her personal recollections, it is clear that despite her enduring fondness for him, they differed in matters of belief, Shields holding ‘terribly narrow religious views’. Through Mills’ portrait of Shields and his circle, we glimpse the freethinking Pre-Raphaelites such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown, with whom she shared much in common. Her own work, of the Arts and Crafts tradition, was displayed alongside examples of theirs in a 1960 exhibition entitled ‘The Pre-Raphaelite Influence’ at Leighton House, London.

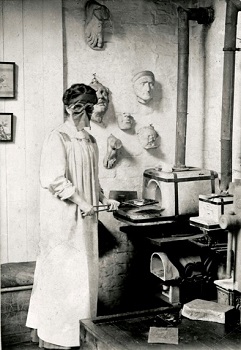

Mills was an accomplished artist, exhibiting at the Royal Academy and the Paris Salon, the latter earning her silver and bronze medals from the Société des Artistes Français. A reviewer in The Times commented that ‘she cannot fail to give pleasure with her glowing colours and the sheer beauty of her materials’. Ernestine created a commemorative plaque, now in the Museum of London, for the Brackenbury women, Hilda, Georgina, and Marie, to honour their contribution to the suffragette campaign. This was one of a number of pieces produced by Mills for the cause of female suffrage, and used the purple, green, and white colours of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). A brooch by Mills, also in the collection at the Museum of London, uses green, white, and gold: the colours of the Women’s Freedom League (WFL), within which other members of the Ethical Union, such as Lillie Boileau, were active. She also produced pieces for soroptimist clubs (part of an international group of societies devoted to improving the lives of women and girls), including a plaque of the medieval physician S. Hildegarde for the Soroptimist headquarters in London. Notably, a plaque commemorating socialist feminist Zona Vallance, inaugural secretary of the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK), was created by Mills for the Ethical Church.

Herbert and Ernestine Mills were members of the West London Ethical Society for over a decade from 1899, with Ernestine serving as part of its art group and Herbert on its committee. Both turned their skills and personalities to strengthening the early humanist movement, as well as to advancing progressive social reform, Ernestine in women’s rights, and Herbert in medicine.

Ernestine Mills died on 6 February 1959 at the age of 88 and was cremated at Mortlake Crematorium. Among those present were her daughter, Dr Hermia Mills, and representatives of the Society for Women Artists, and the Soroptimist Club of Greater London. Her obituary in The Times described her as:

a vivid personality, well known in Kensington, where she lived all her life. A very unconventional upbringing of late Victorian days made her an Edwardian of the modern school, a friend of Mrs Pankhurst, and a champion of women’s rights. She had a courtesy and sympathy for all and was beloved of a large circle of friends.

As an artist and enamelist, Ernestine Mills supported women’s suffrage through art and action. As a humanist and freethinker, she took an active role in the ethical societies, and applied her values to her efforts for progressive politics and social change. The examples of Ernestine and Herbert Henry Mills illustrate threads of action and activism present from the earliest stages of the Ethical movement, and carried on by Humanists UK today: a rational, compassionate worldview underpinning advocacy for social reform and a fairer, kinder world.

I cling to my tiny philosophy: to hug the present moment. Virginia Woolf, diary entry, 31 January 1940 Virginia Woolf […]

As for Mother Clap, she was present all the Time, except when she went out to fetch Liquors… The Company […]

I have never believed in any formal religion, but I have experienced an emotion that seemed to me religious. In […]

The Humanist Housing Association began in January 1955, founded as the Ethical Union Housing Association to provide affordable homes for […]