This conference is resolved to strive for the achievement of peace, justice and tolerance in Ireland, and holds that outmoded attitudes and traditions which interfere with this achievement should be superseded by more valuable ideas and actions.

First resolution of the conference, 25 October 1969

The first joint conference of humanists in Ireland took place 25-26 October 1969, bringing together the Dublin-based Irish Humanist Association and the Belfast Humanist Group. Michael Lines, representing the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) and the International Humanist and Ethical Union (now Humanists International), attended the conference and produced the report reproduced below.

Key participants in the conference, which took place at the Nuremore Hotel in Carrickmacross, Co. Monaghan, included: lecturer and senator Owen Sheehy-Skeffington, physicist and founder of the British Conservation Society Douglas MacEwan, political philosopher Alan Milne, playwright and personality John D. Stewart, politician, human rights professor, and co-founder of the British and Irish anti-apartheid movements Kader Asmal, and Secretary of the Irish Humanist Association Antonia Healy.

REPORT OF FIRST CONFERENCE OF HUMANISTS IN IRELAND

Michael Lines 6.11.69.

1. Summary

A successful weekend conference was organised jointly by the Irish Humanist Association (based in Dublin, Irish Republic) and the Belfast Humanist Group (Northern Ireland). Some 60 people attended and discussed the political and social situations in both parts of Ireland, and the possibilities of humanist action and co-operation. A resolution was passed in support of work for civil rights and a democratic society by the groups North and South of the border.

2. Organisation

The Conference was held on 25th and 26th October, 1969 at the country Hotel Nuremore, midway between Belfast and Dublin. About 60 people (out of a total of some 200 members of the groups, North and South) provided a good attendance. Credit is due to the Organising Committee, and especially Mr. Stan Potter, for the choice of the venue, the production of Conference brochures and papers, and for the running of the meetings. Michael Lines attended as a representative of the British Humanist Association and of the IHEU; others present included Dr. Douglas MacEwan (who spoke at the Hanover Congress) and Senator Sheehy Skeffington, who represents Trinity College in the Dubin Senate.

3. Conference Sessions

The Saturday sessions were devoted to reviews of the situation in North and South, given by John D. Stewart and Kader Asmal respectively, and to consideration of the practical objectives of the humanist movements by Antonia Healy (Dublin) and Alan Milne (Belfast).

John D. Stewart, a TV personality, described himself as a political humanist, since religion and politics could not be separated in Northern Ireland. Unionism discriminated not only against Catholics, but against many able liberals as well, starving the community of resources of ability. The blame for segregation of education could not all be laid at the door of the Catholic Church while officials talk about the state schools being ‘Protestant’ ones. In the slums and in the open country, people are violently and murderously partisan. “We humanists in Ulster would therefore seem to have a duty to fight the Churches, to oppose them for the terrible damage which they have done and continue to do”.

4. Kader Asmal is a lecturer in law at Trinity College, Dublin, and is active in the Anti-Apartheid Movement in the Republic. He related the present situation there to that which existed when he arrived in the early 1960’s finding that, although the Catholic Church remained a pervasive influence, there had been movement in the direction of an open society. Political authoritarianism was more important to humanists than religious authoritarianism, and there had been articulate opposition to the Criminal Justice Bill, which posed a threat to civil liberties. The fight for a decent, humane society was important, whether the Border stayed or went. Dr. D. MacEwan commented that we had to beware of developing a new sort of intolerance towards religion; the claim that “all problems would disappear if all were humanists” contained a threat of authoritarianism. Kader Asmal agreed that we must not get a reputation for arid anti-clericalism: what was needed was to gain a general acceptance of the right to differ, of the right of minority groups not to be dismissed out of hand.

5. Practical Objectives

Antonia Healy, Secretary of the Dublin Association, said that the quality of our humanism was important if we were to be successful. We had to avoid the danger of becoming irrelevant – a small elect who had “found mankind out”. Rather we should work with the new groups of Christians who were heading for the open society; Mrs Healy instanced a visit by humanists to speak to some Augustinians, which resulted in each side learning to respect the other. Equally, it was important for the education of the humanist group to listen to speakers who disagreed with us. Working for an open society meant action for secular laws, integrated education, equality of men and women and reform of the adoption laws. The Council for Civil Liberties, which had recently held its annual general meeting, appealed to young and radical people, and its concerns were those of humanists.

6. Dr. Alan Milne, lecturer in philosophy at Queen’s University, Belfast, spoke on the practical objectives for the North. Humanists, he said, should not have a blueprint for a future society, but rather a continuously added-to list of the things a decent society should provide. He suggested as immediate priorities in the North support for the Civil Rights movement, support for the findings of impartial enquiries (such as that of the Cameron Commission, and the Hunt Report), and the need to speak out on community relations; humanists should drop their vestigial loyalties and ceremonies. The North had to break the traditional link of the Unionist Party with the Orange Order (the main instrument for the exploitation of Protestant bigotry). The reduction of economic equality would weaken the power of discrimination; Humanists should state practical objectives in this sphere, too.

7. Because of the recent disturbances, the lively discussion centred largely upon the movement for civil rights in the North; finally Dr. Milne and Kader Asmal were asked to draft a statement on the issues for the meeting the next day.

8. The Sunday meeting opened with the passing of the resolution previously circulated:

This Conference is resolved to strive for the achievement of peace, justice and tolerance in Ireland, and holds that outmoded attitudes and traditions which interfere with this achievement must be superseded by more valuable ideas and actions. The first steps to this end are integrated education and secular laws based on evolving values and needs and not on any authoritarian belief or system.

9. Alan Milne and Kader Asmal then proposed their resolution:

This first Annual Conference of humanists in Ireland

It was passed unanimously. The words ‘political affiliation’ in Section ii mean more than might be thought; they were introduced to make explicit the belief that people had the right to work democratically for a change in the system of government – in the North, it has been the assumption that unless you were a Unionist (i.e. supported retention of the partition of Ireland) you were disloyal, and deserved no consideration.

10. Conference then decided to meet again in 1970 and to make the meeting an annual event. Discussion of the form to be taken by next year’s Conference was rounded off by a brief address by Michael Lines, who suggested that the meeting could be kept an informal one as long as practical co-operation between humanists North and South was continued. He said how grateful the humanist movement would be for the way in which those present had upheld humanism in Ireland, and how welcome was their determination to tackle the real issues.

11. Dr. Kevin Healy, from the Chair, closed the meeting, telling members to ‘get up and get on with it.’

The writer, TV and radio personality and social campaigner, Claire Rayner, best known for her agony aunt columns, spent most […]

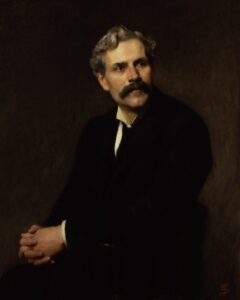

My chosen ground Inscription on the John Hewitt Cairn John Harold Hewitt (1907-1987) was the most significant Ulster poet to […]

The moral value of a belief in eternal life is a doubtful matter. But this is certain, that where rest […]

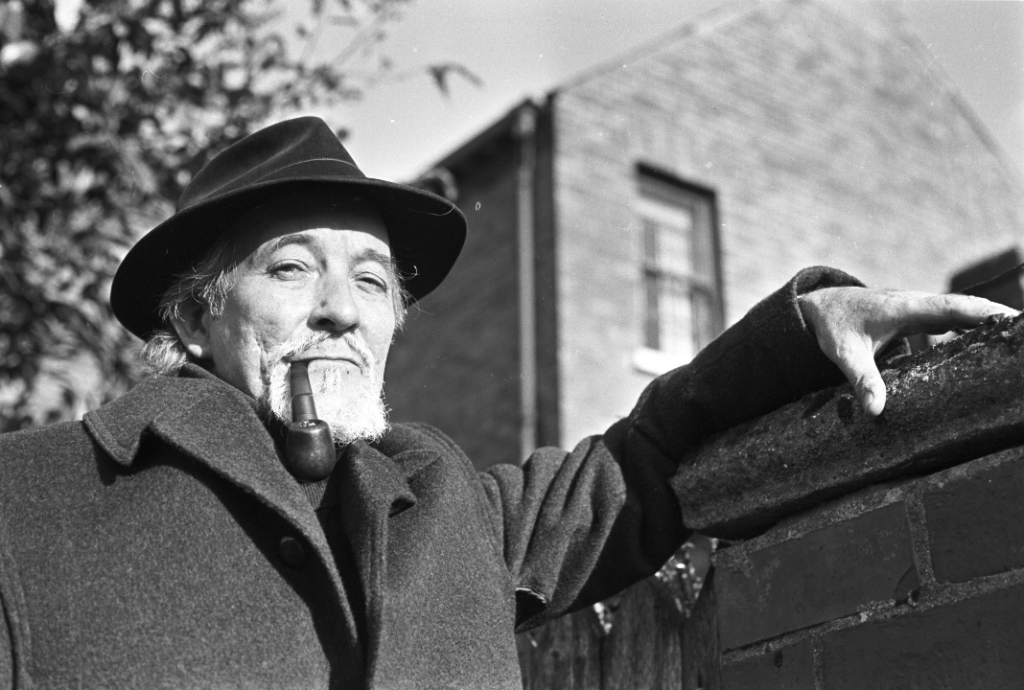

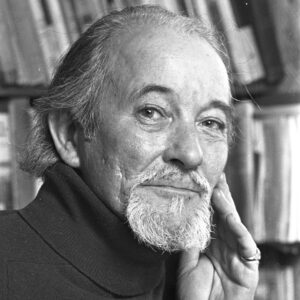

I think I was born a humanist. John D. Stewart, The Honest Ulsterman, May 1968 John D. Stewart was a […]