I think I was born a humanist.

John D. Stewart, The Honest Ulsterman, May 1968

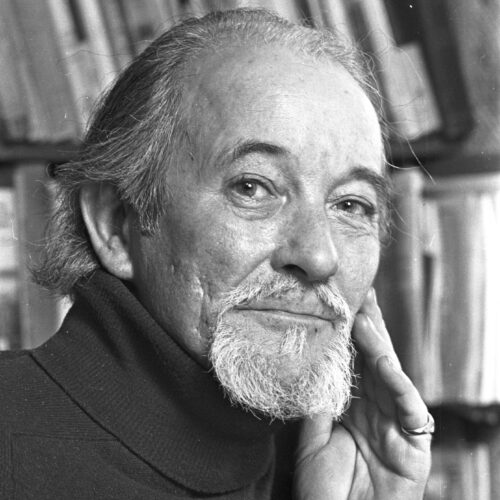

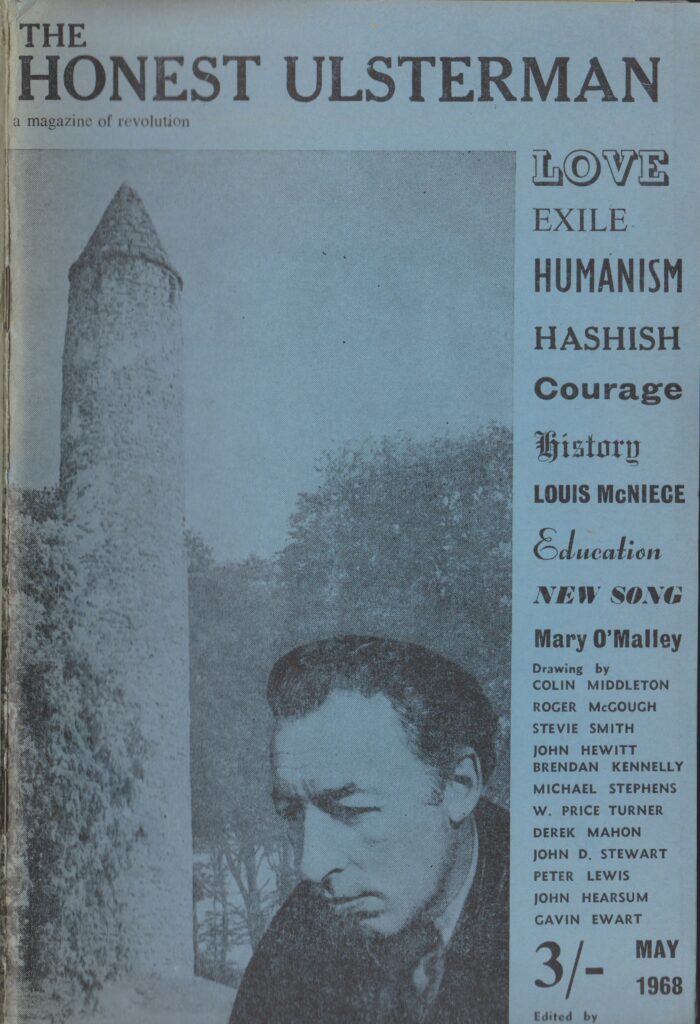

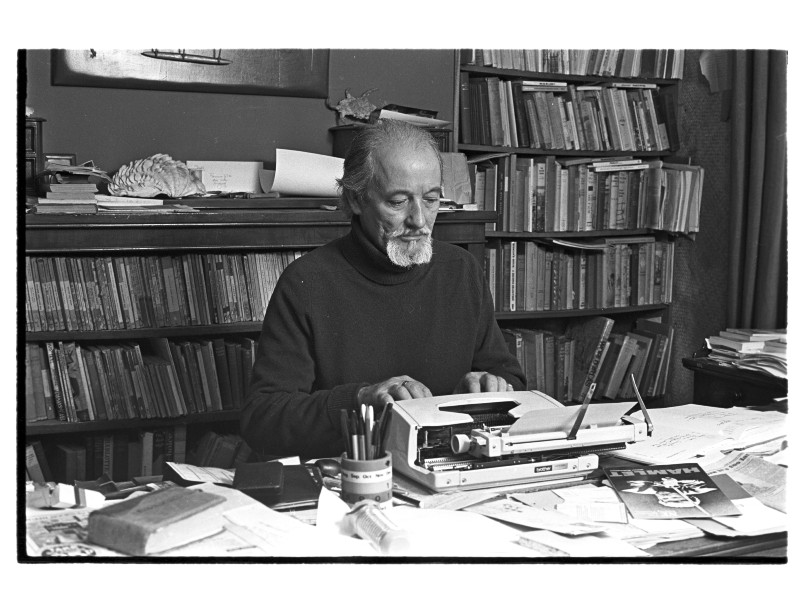

John D. Stewart was a Belfast-born playwright, engineer, journalist, and humanist. He was a prominent voice of the Belfast Humanist Group, established in 1966. Although unusually ill-remembered, his activism echoed some of the core ideals of Northern Irish humanists during a period of profound division and civil unrest. Stewart was also involved with the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, a non-partisan and non-religious organisation who famously campaigned for the equal rights of all Northern Irish citizens. At a time when Northern Irish society was dominated by identity politics and a complex conflict, Stewart offered an alternative way to look at the world.

Stewart described himself as a political humanist, as he recognised the unique relationship between politics and religion in Northern Ireland. In his writings in the late 1960s, a deep sense of frustration towards the divided society surrounding him was evident. This period would become the pre-cursor to 30 years of brutal civil conflict in Northern Ireland, known as the ‘Troubles’. Though not a religious war, the ‘Troubles’ was dominated by politico-religious identity blocs. Stewart viewed humanism as an offering of unity and peace, and a way to diminish unfair systems of religious and political power.

I decided to cry out “A plague on both your houses” and declare myself a Humanist.

John D. Stewart, The Honest Ulsterman, May 1968

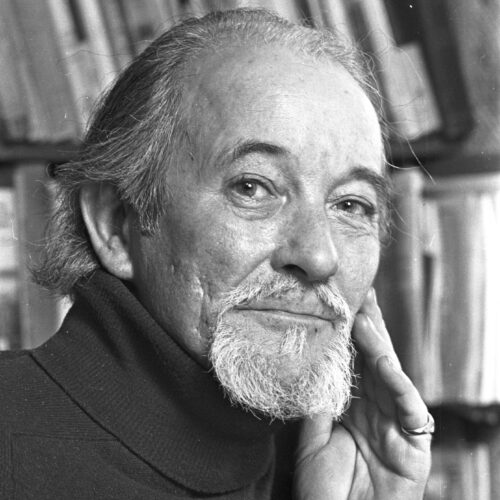

Stewart was a regular contributor to The Honest Ulsterman, a magazine which aimed to showcase writers of varied beliefs and backgrounds. It also featured contributors like Seamus Heaney and John Hewitt. In a piece titled ‘Let Us Be Human’, he situated his humanist ideals within the political realities of Belfast. He vehemently criticised those who used religion as a ‘badge of political power’ and a means to enact violence and terror. He described his decision to identify as a humanist as a liberating moment, enabling him to reject the divisive identity politics of the time.

It is worth noting that Stewart adopted a slightly harsher anti-religious stance than the majority of his peers in the Belfast Humanist Group. This organisation was founded in 1966, and created a community for humanists to express their beliefs and campaign for change. Their activist work included appealing to the City Council for the use of sports fields and playgrounds on Sundays for children, as these were often closed for religious reasons. Stewart regularly spoke at Belfast Humanist Group meetings. He discussed the prevalence of religious discrimination in Northern Ireland, and encouraged humanists to have courage in their convictions (Belfast Newsletter, 26 October 1967).

Stewart played a formative role in the emergence of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA). This organisation became well-known for its peaceful marches and protests in favour of civil rights for all in Northern Ireland, including Catholics. Stewart was selected to be chairman of their first meeting, in the Belfast War Memorial Building in November 1966. The group’s main objectives were defending the basic freedoms of all citizens, highlighting abuses of power, and demanding freedom of speech, assembly and association. Although NICRA did not actively label itself as humanist, its activism was non-partisan and non-religious, just like the Belfast Humanist Group’s. It is clear that Stewart’s own humanist values were closely intertwined with his political activism.

John D. Stewart wrote about his humanist identity in a warm and astute manner, and his literary and activist contributions encouraged a new outlook on societal values and morality in Northern Ireland. He recognised the distinctive position of religion in Northern Irish society, and framed humanism as an escape from the destructive cycles of religious division. Despite being poorly documented and remembered, his ideas about the entanglement of politics and religion still resonate in humanist work in Northern Ireland today.

By Jess Martínez Gorman

Her beautiful life, her truth, her unwearied charities, proceeded from her own heart. They were not inspired by any thought […]

And in these four things, opinion of ghosts, ignorance of second causes, devotion towards what men fear, and taking of […]

Rochdale Pioneers Museum occupies the building at 31 Toad Lane where, in 1844, 28 working class people came together to […]

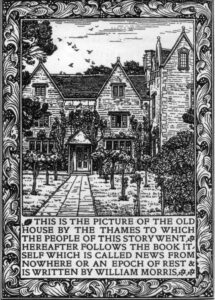

Kelmscott Manor was the country home of the writer, designer, and socialist William Morris from 1871 until his death in […]