No one who came in contact with her failed to recognize in her fearlessness, honesty for the sake of honesty not merely as the best policy, and a capacity to take an exceptionally detached view of all things.

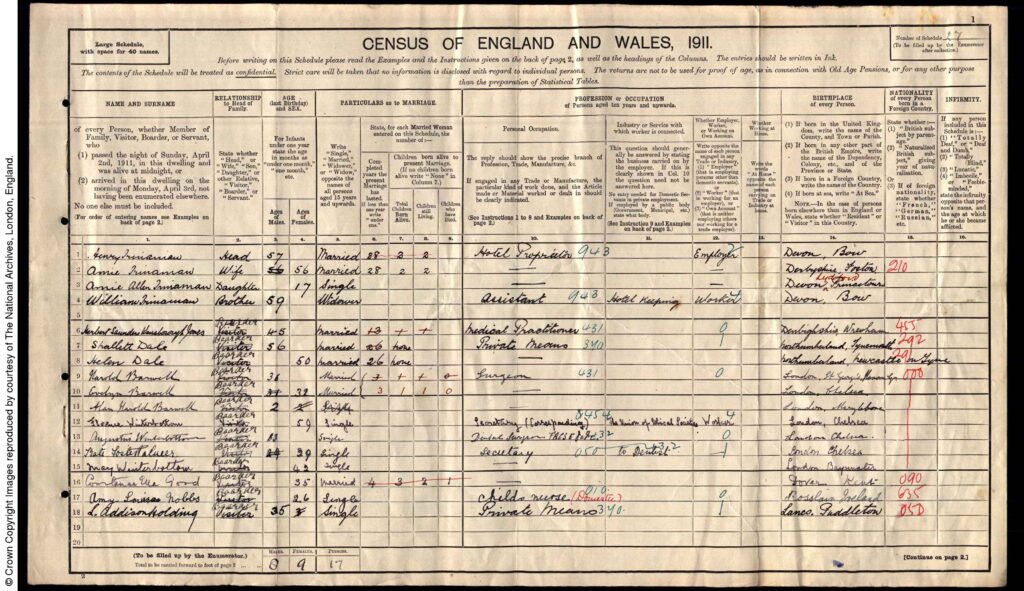

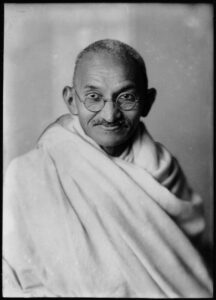

Mohandas K. Gandhi

An active part of the Ethical movement for over thirty years, Florence Winterbottom was secretary of the Ethical Church, Emerson Club, and of the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK), as well as twice chair of the Union’s annual congress. She was also a close friend and correspondent of Gandhi, who described Winterbottom as ‘a leading light’ of the early organised humanist movement, and ‘among the rare men and women who find service its own reward’.

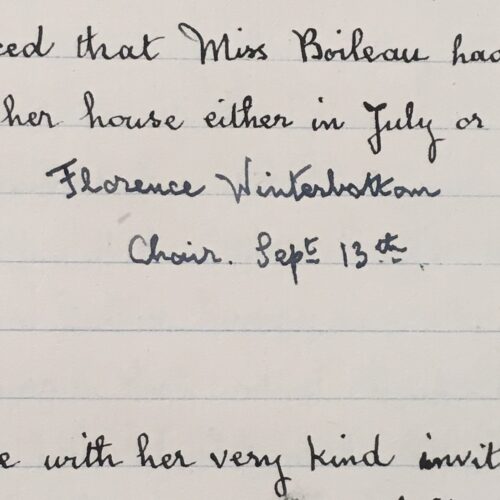

Born in Chelsea in 1851, Florence Winterbottom was the tenth child of Edwin John, a dentist, and Mary Winterbottom (née Mence). In 1892, she was a founding member of the West London Ethical Society, remaining one throughout subsequent decades, and becoming one of the Union of Ethical Societies’ most loyal workers.

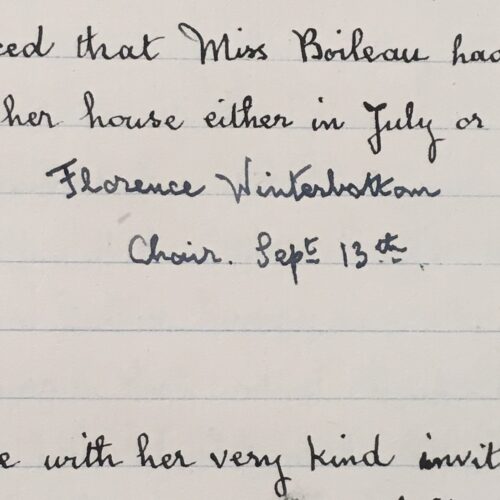

In the words of Gustav Spiller, ‘Miss Winterbottom concentrated on secretarial and organising work and never spared herself in this respect.’ She was a decades-long fixture on the Council, including as its chair, and that of the annual congress of the Union of Ethical Societies. She was an active member of the Women’s Group of the Ethical Movement and, like many others within the ethical societies, a supporter of women’s suffrage. In 1911, Winterbottom was put forward by the Ethical Church (then the home of the West London Ethical Society) to become licensed to perform and register marriages. This was rejected by the Registrar General on the grounds that ‘a woman is ineligible for the appointment of Authorised Person just as she is for the appointment of Registrar of Marriages’.

Florence Winterbottom first met Gandhi in 1906, from which point she corresponded with him weekly until her death two decades later. Gandhi, an admirer of the Ethical movement, discovered William Mackintire Salter’s Ethical Religion in the same year, and translated its ‘substance’ into Gujurati for publication in his journal Indian Opinion for eight weeks of 1907. Gandhi described Winterbottom as ‘one of the most constant and painstaking supporters of the [Indian] cause in South Africa’. Also writing that:

Though intensely English, she was equally intensely international… When people tell me that non-violence is of no effect as far as English people are concerned, I renew my faith in non-violence and in English nature, or better still human nature, by thinking of instances like those of Miss Florence Winterbottom.

In his own recollections of her, Gandhi acknowledged that Winterbottom was little known in England, but nevertheless made an evident impression on him. She remained an unflinching (though not unquestioning) supporter of his, and a devoted correspondent.

Florence Winterbottom died on 18 December 1926. The Ethical Union’s annual report described her as ‘ever a most devoted and loyal adherent of the Ethical Movement, and for many years an enthusiastic worker as the Union’s Secretary.’ Symbolically, she left her typewriter to the Union.

…she belonged to that class amongst the English who seek out and befriend forlorn causes in the teeth of odium, ridicule and opposition… she sought us out, she offered me a platform, she studied the question and in a variety of ways helped the cause that at that time had only a few chosen friends in England.

Mohandas K. Gandhi

Like Zona Vallance, Lillie Boileau, Nellie Freeman, and many other women of the ethical societies, Florence Winterbottom’s contribution to organised humanism has been comparatively overlooked. However, through key organisational roles, her part in promoting, growing, and strengthening the Ethical movement was significant. Gandhi’s recollections are among the very few mentions of her that survive, but give a clear indication of Winterbottom as bold, thoughtful, and compassionate; typical of the men and women who drove the early humanist movement.

There is no hope but us. There is no mercy but us. There is no justice. There is just us… […]

…the only efficient, the only decent prayer, is Action. John Galsworthy, ‘Philosophy of Life’ in Glimpses and Reflections (1937) Best […]

…for the Promotion and Advancement of Science, Literature and Art Trust deed of the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institute […]

The international significance and reputation of Mohandas Gandhi is well-known, but his involvement with the burgeoning humanist movement during the […]