The Conscience has eclipsed the Scriptures; Science has destroyed the belief in Divine Interposition; Democracy and Civism have shown men how to help themselves… a radical reconstruction of belief has become inevitable.

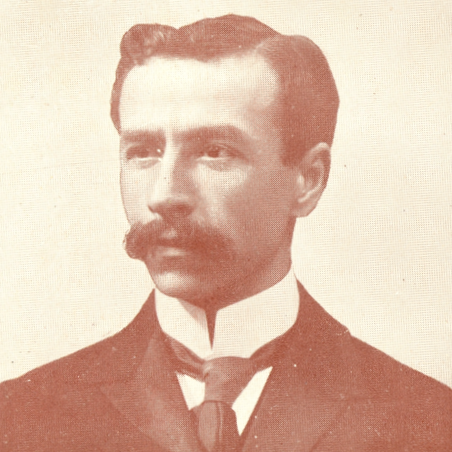

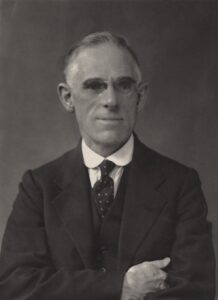

Gustav Spiller

Gustav Spiller was a lifelong humanist: an active member and historian of the Ethical movement, as well as a writer on ethics and sociology. Entirely self-taught, Spiller was nonetheless devoted to the education of others, as well as to the possibilities of international cooperation. He helped to organise the inaugural International Moral Education Congress in 1908, as well as the First Universal Races Congress in 1911, and authored or contributed to a number of books designed for ‘ethical worship’.

Born in Budapest in March 1864, Gustav Spiller left school before he turned 12, thereafter working 65 hour weeks as a compositor. On moving to London in 1885, he continued in this trade, as well as keeping up the continuous programme of self-study maintained throughout his life. From 1893, he worked as a printer for the Bank of England, until 1901, when he became a lecturer for the Ethical movement. Inspired by the discourses of Stanton Coit at South Place Ethical Society, Spiller was one of the founders of the East London Ethical Society in 1890, along with Frederick James Gould, centring ‘the development of good character and the promotion of right conduct on a purely human basis’. In 1904, he took on the position of secretary for the International Union of Ethical Societies, which had been founded eight years earlier.

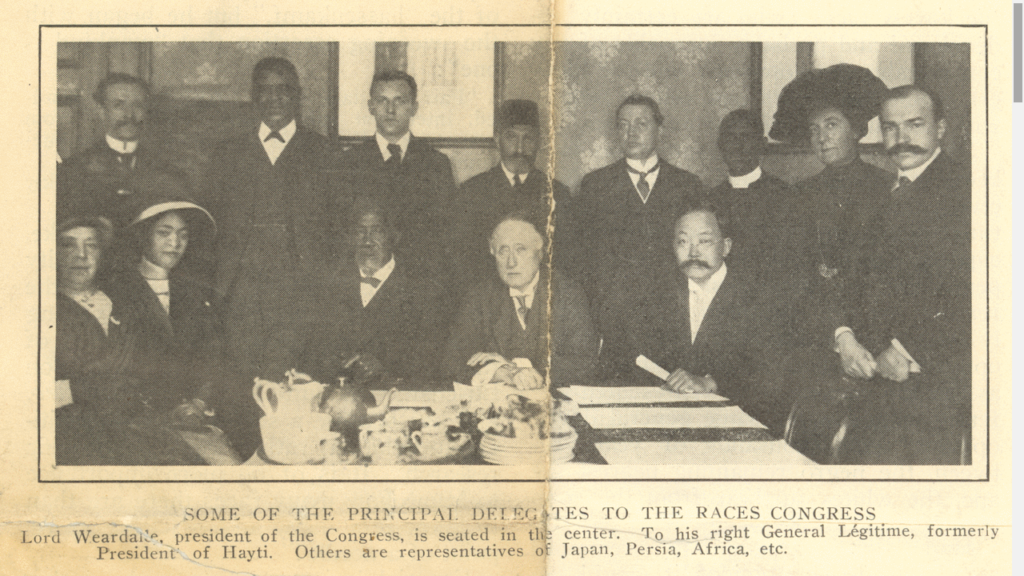

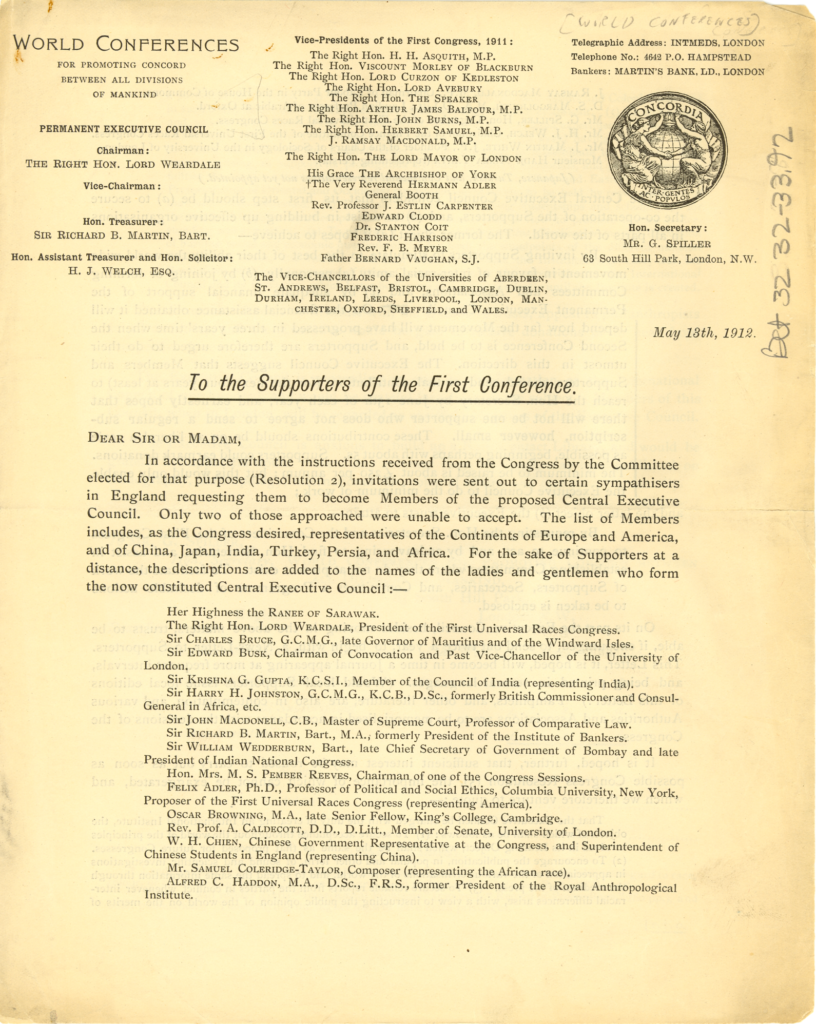

In this role, Spiller organised the first International Moral Education Congress, which took place at the University of London in 1908. In 1911, he was instrumental in creating the First Universal Races Congress, an effort towards greater unity between countries, creeds, and races. Its intention was

to discuss, in the light of science and the modern conscience, the general relations subsisting between the peoples of the West and those of the East, between so-called white and so-called coloured peoples, with a view to encouraging between them a fuller understanding, the most friendly feelings, and a heartier co-operation.

The First Universal Races Congress included representatives from 50 countries, among them politicians, academics, and reformers of international notability. Attendees over the conference’s three days in late July heard papers from W. E. B. Du Bois, J. M. Robertson, and Franz Boas, and attendees included suffragist Jane Addams and writer Alain Locke, who would go on to be one of the founders of the Harlem Renaissance. In records of both the International Moral Education Congress, and the First Universal Races Congress, Spiller’s commitment and organisational devotion was noted. A. C. Haddon wrote afterwards of Spiller’s ‘indefatigable energy and enthusiasm’, ‘ably assisted’ by his wife, suffragist Nina Spiller.

From 1920-1924, Spiller worked for the International Labour Office: the secretariat of the The International Labour Organisation, an agency of the League of Nations in Geneva. The ILO sought to advance social justice and equality by establishing international standards for labour. From 1925 he was the Honourable Secretary of Stanton Coit’s Ethical Church. In 1926, he joined the council of the British Sociological Society (of which he was a founding member), on which he stayed until his death.

Gustav Spiller died on 16 February 1940, at the age of 75. The Ethical Union’s annual report remembered his ‘scholarship and selfless devotion’ to the movement. His wife, Nina, active in both the Ethical Union and International Alliance of Women, died almost 30 years later, in 1968.

Though relatively unremembered today, Spiller was one of the primary drivers of the early Ethical movement, eclipsed somewhat by the better known Stanton Coit. Archives worldwide hold items of Spiller’s correspondence with giants of reform, including W. E. B. Du Bois and Jane Addams, as well as records of the groundbreaking events he played a key role in creating. His work both within and outside of the Ethical movement testifies to his devoted efforts towards peace, social equality, international cooperation, and progressive reform.

Harry Snell was a socialist politician and campaigner, a devoted advocate of the Ethical Movement and a key figure in […]

What an emancipation it is, — to have escaped from the little enclosure of dogma, and to stand, — far […]

Not to be confused with Kelmscott Manor, Kelmscott House was the London home of designer and socialist William Morris from […]

Emilie Holyoake-Marsh, daughter of George Jacob Holyoake, was an activist for worker’s rights and women’s suffrage; an advocate of co-operation, […]