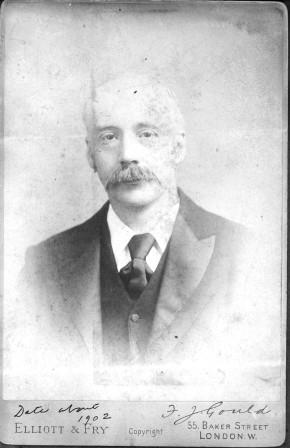

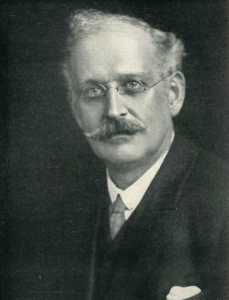

F.J. Gould was an influential educationist, writer, and humanist, whose tireless work towards secularising education helped to lay the groundwork for the ongoing efforts of Humanists UK today. As an organiser in the Ethical movement and a lifelong advocate of moral instruction in schools, Gould’s ideas became well known among teachers throughout the UK, and internationally. He was a leading light in many of key initiatives surrounding secular education, as well as a founding member of the East London Ethical Society, and the Rationalist Press Association.

Frederick James Gould was born in Brighton, on 19 December 1855. His father was a jeweller and his mother a dressmaker. First attending school in London, he was elected a chorister of St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, in 1865. Here, Gould met Canon Wriothesley Russell, who supported his further education at the village school in Chenies, Buckinghamshire. From 1871 he taught at the school, until in 1877 he became the head teacher of the church school in Great Missenden: ‘But the two stupidities – one of the secular code, the other of the crude Bible-teaching code – were destined to make me a two-fold rebel.’

Gould resigned his post in 1879, his religious faith lost and his belief in the suitability of national education shaken. He took up a post for the London School Board in Turin Street, Bethnal Green. He later wrote:

In Missenden Churchyard I had, as it were, left the shattered fragments of my Evangelical beliefs. With a thin and feeble Deism, which diminished daily and soon died, I was facing a class of three-score London boys, many of them ill-clad and ill-fed, and I was treading a very novel road in a great city.

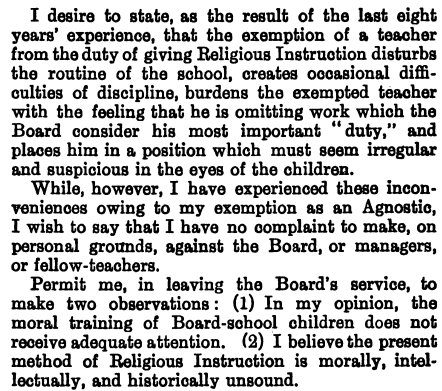

Described in this period by others as ‘half a Christian’, and by himself as ‘half a Rationalist, if not more.’ Gould still attended a Bible class at St. Thomas’ Square Chapel, Hackney, but visited Old Street’s Hall of Science, and debated with the Christian Evidence Society. He appreciated the Bible now as a ‘human poem’, and had begun to contribute to Bradlaugh’s National Reformer, and the Secular Review (later the Agnostic Journal). In 1888, the School Board noted Gould’s writing and lecturing on rationalist subjects and, following discussions with him, arranged a transfer to Northey Street, Limehouse, where he would maintain his salary but be excused from delivering religious instruction.

For the following eight years, Gould remained there, ‘increasingly hating the hard and mechanical system then in vogue,’ though gaining confidence ‘in effective modes of story-telling in biography and history’. Leaving the classroom for the head teacher to deliver Bible lessons, and returning 45 minutes later, Gould felt ‘alien… in the school, not of it.’ These formative experiences in the worlds of rationalism and state education set Gould on the path to becoming a leading figure in the early organised humanist movement. He noted that from 1888 ‘social progress and the humanizing of thought and education’ became his singular focus.

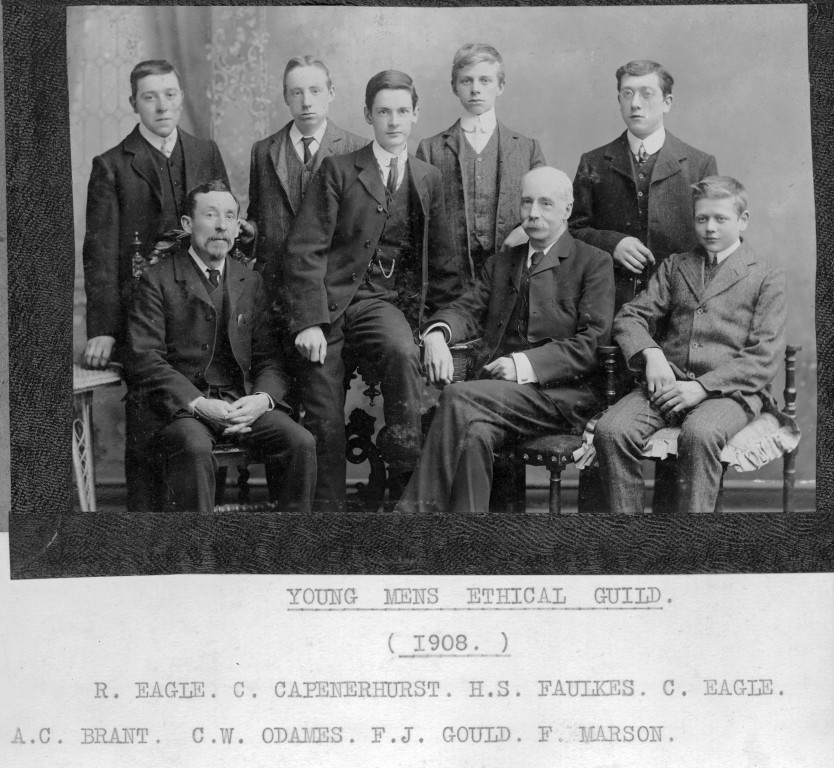

In 1889, Gould was a founding member of the East London Ethical Society, alongside two other leading figures of the Ethical movement: Gustav Spiller and Stanton Coit. The East London group was, from its origins, a diverse and largely working class society, and provided secular Sunday schools, youth groups, entertainment, and lectures: all on a ‘purely human basis’. Here especially, Gould developed the methods of non-theological moral education which would animate his life’s work and writings. He found ‘in story-telling on themes of personal and social conduct, a blessed relief from the harsh methods of the Board School and an experimental field for humanist ideas.’

From 1890, Gould was also actively involved in the evolution of the Rationalist Press Association, which began as the Propagandist Press Committee: ‘plotting to set the Thames on fire with tracts and cheap volumes.’ Charles A. Watts’ ‘business mind’, wrote Gould, ‘was already outlining the most successful humanist publishing enterprise in the annals of literature’ and ‘six years later the brilliant butterfly of the Rationalist Press Association emerged from the humble chrysalis of the R.P.C. [Rationalist Press Committee], and the flash of its wings has been seen in five continents.’

In 1896, Gould left the School Board and, at the invitation of Stanton Coit, became a full time worker for the Ethical movement:

For three years I laboured without ceasing, in lectures, in teaching a variety of Ethical Sunday-schools, in conferences… in the pages of the Ethical World… and in the establishment of the Ethical Union, the Moral Instruction League, and a Moral Instruction Circle.

Gould became secretary of the Leicester Secular Society in 1899, remaining there until 1910. During his time as secretary of the LSS, Gould also served on the Leicester school board (1900–02) and the town council (1904–10). He remained associated with the Moral Instruction League (which became the Moral Education League in 1909), and in 1910 took on the role of ‘demonstrator’. In this capacity, he travelled across the UK, as well as to the US, and India, lecturing on and promoting the cause of non-theological moral education.

Gould died at home on 6 April 1938 and was cremated on 11 April at Golders Green crematorium. Two of his three children predeceased him; his daughter Eva Minna at six, and son Francis in 1917. His wife of nearly 60 years, Mahalah Elizabeth, died in 1944.

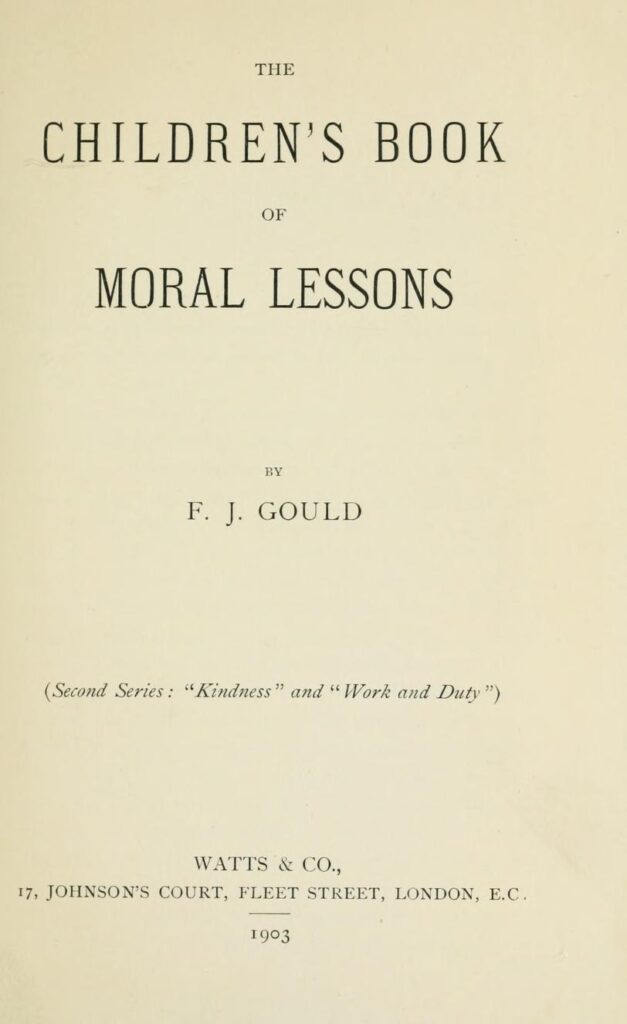

As a lifelong champion of moral education, Gould embodied the concern for inclusive ethical instruction, free from religious bias, which continues in the work of Humanists UK today. Gould produced nearly 50 books on subjects relating to moral education, as well as hundreds of articles, pamphlets, and teaching materials. The work of Gould and his colleagues in the early organised humanist movement was pioneering in pushing for secular, rational, and reasoned education for young people, freed from the strictures of religious doctrine. One area of which Gould himself wrote particularly proudly was sex education, declaring that:

Nothing more finely shows the superiority of humanist thought than our quite modern readiness to meet the problem of education in the field of sex.

This too formed part of an ongoing tradition of advocating sensible, scientific, and compassionate attitudes towards sex, sexuality, and sexual health among humanists, and in the efforts of Humanists UK today. Humanists and secularists have long been pioneers in challenging harmful attitudes concerning contraception, abortion, sexuality, and reproductive rights. Humanists UK continues to campaign for rational reform in these areas, and for the provision of ‘good quality, age and developmentally appropriate relationships and sex education in schools’.

Charles Albert Watts was a lifelong promoter of rationalism, and the founder in 1885 of Watts’s Literary Guide, still published […]

I have ever considered that the only religion useful to man consists exclusively of the practice of morality, and in […]

Conservation… draws us towards not only a scientific but a philosophical and historical approach to the problems of the earth […]

I have devoted my time and fortune to laying the foundation of a society where affection shall form the only […]