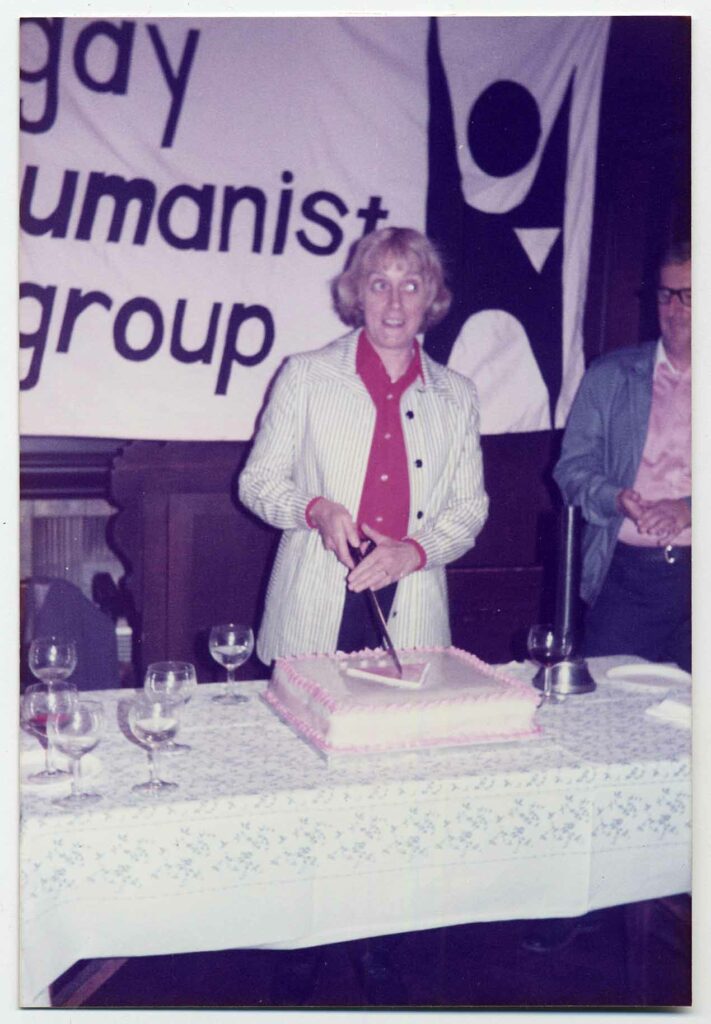

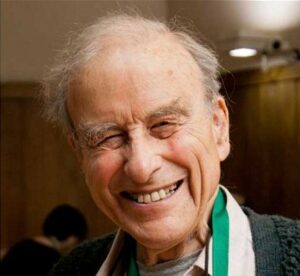

‘Separate Development? Out of the closet, into the ghetto’ was a talk given by writer and activist Maureen Duffy on 17 March 1980 for the Gay Humanist Group (now LGBT Humanists), of which she was the inaugural President. The talk was subsequently published by the Gay Humanist Group (which had been founded in the previous year) and is reproduced below in its entirety. In it, Duffy refers to the blasphemy charge levelled at Gay News by Mary Whitehouse — the first of its kind for half a century — which was partly responsible for the group’s formation, and about which she had published, in 1977, The Ballad of the Blasphemy Trial.

One of the first British women to come out publicly as a lesbian, Duffy became a prominent activist for LGBT rights, and a champion of the visibility and advocacy she argues for in this talk. She was also, with Brigid Brophy, a leading figure in the successful campaign for the Public Lending Right, which entitled authors to payment from the public lending of their works.

As this is my first honorary president’s address, will you please forgive me if I make one or two of the sort of remarks honorary president’s are supposed to make on these occasions, rather than going immediately to the subject of my talk this evening. I think these remarks are linked with the main topic for this evening.

The aims of the Gay Humanist Group are printed on their leaflet and read:

These seem to me a Catch 22 set of aims: you’re caught one way, or you’re caught the other.

I want to say something about why I think there should be a Gay Humanist Group. I see our function, I hope, not as simple church bashing. I think that would be a very negative way for us to go about being an association of any kind. I think our aims, should be twofold, bearing in mind that we will all see them slightly differently, and I think that’s right, too.

One very important aim for this association is to speak up wherever necessary from the rationalist stance, in particular where homosexuals are involved or affected.

One very important aim for this association is to speak up wherever necessary from the rationalist stance, in particular where homosexuals are involved or affected. I think particularly of two recent reports, one emanating from the Anglican Church and one from the Roman Catholic Church, on homosexuality. It could be argued that these reports were intended for internal consumption by members of those respective groups, but when such announcements are made the press always gets very, very excited. Any mention of sex always sets the press off, and homo sex will set if off twice as quickly and fierily. If it can also be involved with morality the papers, and indeed all the media, are going to have a field day. This they did in the case of these reports. It could, as I say, be argued that we should have said nothing at all, because in a sense they were for the internal consumption of those groups, perhaps suggesting how they should regulate their lives. But such pronouncements are not kept simply for the people for whom they are intended. As soon as they appear in the press or are mentioned on television, they become common property; they become liable to influence the whole community. Therefore we cannot be quiet in such a position, particularly if we feel that what is being said may be hurtful or damaging, certainly unhelpful, in some way. And we have to make as bold an attempt to put our view across on the various media as other groups and organisations, because if we don’t our views will simply go by default and anything that we have to offer which could be valuable or helpful to some people will not be heard. So it is one of our functions to speak out whenever necessary, and particularly to present the alternative voice.

The second of our functions, as I see it, is to make our contribution to what I should call the ethics of compassion – and I realise that this perhaps takes a little definition on my part. I would define it as a fluid morality, based on a perception of fellowness, fellow feeling, fellow suffering. It is immensely appealing to a writer because it requires a continuing act of the imagination in order to identify with others and it also needs the continuing exercise of the reason if there is to be some bony structure to it, for it not to become mere sloppiness. As war is far too important to be left to the generals, so morality is far too important to be left to the theologians. Too often they take an idealistic view in the field of human relationships – and by idealistic here I mean idealistic in the very narrowest sense. I myself mean it perhaps in the sense in which Kierkegaard meant it. What we have to consider is, if I can be allowed a very old fashioned term, an existential view. Theologians hanker after what should be theologically, rather than a compassionate participation in what is. I put it to you that the true humanist is always an existentialist, in the sense that he believes nothing is given except oneself and that every decision has to be lived and relived. The ethics of human compassion apply to the whole human field and the whole human field gives the positive sense in which I am prepared to use the term “humanist” as distinct from the more precise “secularist”.

The second of our functions, as I see it, is to make our contribution to what I should call the ethics of compassion… a fluid morality, based on a perception of fellowness, fellow feeling, fellow suffering.

Now in that section of the human field which is the gay, or as I would prefer to call it the homosexual, part, the ethics of compassion need to be constantly practised as they do in any distinctive minority group and in the whole field of our relationships, with other animals in particular. Homosexuals are born into or fashioned in, depending on whether you view our original sin as genetic or psychological, a world whose social systems are based on the sexual, emotional and social needs of the majority who are heterosexual or bisexual. It may well be true that mankind’s simple state is bisexual. However, in order for the species to continue a lot of hetero sex has to go on and therefore there is a strong biological pressure towards a predominantly heterosexual society which will produce and nurture children to continue the species. This biological drive is reinforced in human beings by our passion for constructs, by which we embody and reinforce our biological drives. In order to do what other species do by instinct, we have to make social, moral and aesthetic images and organisations. The homosexual is therefore not only largely out of the biological race, but may feel excluded from the whole arena where races are taking part. This leads to guilt and collapse when the full weight of heterosexual society is turned against us. Some homosexuals in this state may turn to religion for support and comfort and we should attempt to understand this if they do. Others may become the cynical followers of the round of cottages and clubs and so on. The other temptation is to retreat to the closet and bolt the door, to pretend to the majority that you are one of them while following a hidden life of your own. The results of this have been blackmail, neuroses, secretiveness, unloving and unlovely clandestine sexual encounters and bitter marriages. This is the world in which any of us over the age of 40 grew up. When I first came out, as the expression now is, (though nobody knew the expression in those days) I remember it was even thought very risque for a woman to wear trousers with fly fronts. You could be spotted in the street immediately and spat at or called after if you wore buttons down the front instead of down the side. So the world has progressed!

When I first came out, as the expression now is, (though nobody knew the expression in those days) I remember it was even thought very risque for a woman to wear trousers with fly fronts… So the world has progressed!

Then came the much maligned permissive sixties and in common with other previously locked out groups, homosexuals began to demand the basic human rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Some progress was made, some legal and social restraints were removed. The general public certainly began to show more compassion for homosexuals (I mean compassion in the very best and most precise sense) and more people were prepared to recognise their own bisexuality. More famous figures were prepared to come out and say: “Yes, I always have been, but I never liked to say”. Those for whom it was easy to come out came out. It got us out of the closet and into the ghetto. It gave us solidarity, gay discos, unisex jeans and hairdressers. It also brought us by way of a backlash eventually Mrs Whitehouse. (I’ve always thought that the term backlash must refer to one of the nastiest pieces of sado-masochism invented.)

And the ghetto is where we collectively rest at the moment. Progress in the development of a true ethic of compassion has stopped. Many homosexuals still carry an intolerable Pilgrim-like burden of guilt for being different. Many still cannot tell family or friends.

The swinging sixties became the swingeing seventies. (Personally, I’m looking forward to the return of the gay nineties – if I live that long.) And the ghetto is where we collectively rest at the moment. Progress in the development of a true ethic of compassion has stopped. Many homosexuals still carry an intolerable Pilgrim-like burden of guilt for being different. Many still cannot tell family or friends. Coming out is as far as the door of Adams, where we can all dance together and cling together without being spat on by the straights, we can be outrageous camp or leather butch and cover our damaged personalities with mask role and disguise. Only perhaps when we fall in love may we hanker to lead a life more like that of the majority and look for their acceptance.

It’s fashionable in some quarters, particularly transatlantically, to argue for our separate development in the ghetto and that we shouldn’t allow our more tolerant view and life-styles to be contaminated by rigidly straight ones and pseudo-conformity. I would endorse a great deal of this, particularly the part about tolerance and tolerance of each other, whether we are raving queens or tweed-suited, respectable school teachers. At the same time, it seems to me that the dangers and restrictions of the ghetto outweigh its benefits although I do see that there may long be a need for it as a rehabilitation centre, a comfort station on the way from the closet to the main square. Although the ghetto is often cosy, and from the writer’s point of view breeds fascinating language and style and an identity of its own which can be exploited in neo-realistic artistic terms, the dangers of it as seen in recent history, whether that history is written in Warsaw or Soweto, are far too great. We have to leaven the lump of society with our visible and acknowledged presence in it to prevent social or actual pogroms. I believe that we must grasp our own existence and participate in the whole of human life. It’s true that we have to develop the ethics of compassion for each other, but we also have to exercise it towards all other human beings straight or gay, to use ghetto terms.

We have to leaven the lump of society with our visible and acknowledged presence in it… I believe that we must grasp our own existence and participate in the whole of human life.

I first set this view out fifteen years ago (at least I’m being consistent) in a book called The Microcosm. I’d like to finish by quoting what I said at the end there, as I think it is still very much to the point. At the end of the book the main character, Matt, decides to come out of the ghetto, which she describes as the rock pool, and she explains how she feels:

‘When I first found out about myself I wasn’t shocked or frightened as some people are. Instead I looked around for an idea that would cover the situation, make sense of it. You’d say it was a typical reaction of course, just what you’d expect of me. Anyway I conceived this idea of the rockpool, of the gay world as a universe in little where you could find all the human processes, life and death and love, rich and poor, successful and otherwise, moral and a-moral, just as in a pool on the shore you can find crustaceans and fish, dozens of different forms of plant and animal life in as many colours, a microcosm if you like. And you can sit beside the pool day after day studying them until you become an expert in your own little field. Then I found I wasn’t studying them from a distance, from a nice safe seat on the rocks but swimming about down there among them, subject to all the same laws and problems and I accepted this for a long time because at the back of my mind there was another idea too which I can’t explain without either being drunk and then it doesn’t matter, I wouldn’t care, or sounding so pretentious I couldn’t bring it out in cold blood. But it’s something to do with involvement and what Steve’s father, the vicar, would call suffering. Does any of this make sense to you?’

‘Go on.’

We’re part of society, part of the world whether we or society like it or not, and we have to learn to live in the world and the world has to live with us… just as in the long run it’ll have to do with all the other bits and pieces of humanity that go to make up the whole human picture.

‘For a time this was right and necessary because I still had enough consciousness of what I was doing for it to be valid but gradually I began to lose that consciousness and become a tiny organism in the life of the rockpool, gasping for an existence like all the rest, adding to the problems instead of helping to solve them and just as frightened of the open sea as everyone else. We’re terrified of what’s out there, of the competition, of being laughed at, of having to stand up and hold our own and so we make this little world for ourselves where we can be safe and comfort each other with what a dreadful life it is and how handicapped we are until being queer becomes a full-time occupation and there’s none left over for anything else. But it’s a fallacy. There’s no such thing as a microcosm. You’re walking along the shore and you come across the rockpool. You think it contains all you want, all varieties of human experience and just as you’re becoming thoroughly absorbed in it a great wave washes over it and you realise it’s not complete in itself, it’s only part of the whole and all the little fishes who’ve been swimming frantically round and round, and the crabs who’ve been hiding under the stones half buried in the sand with only a pair of frightened eyes peering out, have to make a run for it out into the open sea because that’s the only place they’ll ever grow up, and the only ones who are left in the pool are those who’re too slow-moving, too firmly attached to their rocks and their way of life to get out. We’re part of society, part of the world whether we or society like it or not, and we have to learn to live in the world and the world has to live with us and make use of us, not as scapegoats, part of its collective unconscious it’d rather not come to terms with but as who we are, just as in the long run it’ll have to do with all the other bits and pieces of humanity that go to make up the whole human picture. Society isn’t a simple organism with one nucleus and a fringe of little feet, it’s an infinitely complex living structure and if you try to suppress any part of it by that much, and perhaps more, you diminish, you mutilate the whole.

Society isn’t a simple organism with one nucleus and a fringe of little feet, it’s an infinitely complex living structure and if you try to suppress any part of it by that much, and perhaps more, you diminish, you mutilate the whole.

And there’s one more thing, just one more. Not only can you say that the microcosm doesn’t exist but it shouldn’t exist because it’s an idea that springs from the fragmentation of experience and knowledge. We don’t learn do we? We develop all our sciences, archaeology, cosmology, psychology, we tabulate and classify and cling to our sacred definitions, our divisions, without any attempt to synthesise, without the humility to see that these are only parts of a total knowledge. I suppose it’s hard when you can’t even begin to touch most fields of human activity today. Coleridge was the last man who was supposed to have read almost every extant book wasn’t he and even he wouldn’t be able to keep up now. But somehow we ought to be able to keep the idea of the totality of experience and knowledge at the back of our minds even though the front’s busy from morning til night with the life cycle of the liver fluke.’ She paused for a moment and then went on, ‘Some people would say I’m running away, refusing to acknowledge the facts of our life as they are, not taking my share in the common suffering but that’s not true. I’m not running. I’m just taking up my whole personality and walking quietly out into the world with it. We’ll see what happens.‘

‘Some people would say I’m running away, refusing to acknowledge the facts of our life as they are, not taking my share in the common suffering but that’s not true. I’m not running. I’m just taking up my whole personality and walking quietly out into the world with it. We’ll see what happens.‘

Talk given on 17 March 1980. At the Conway Hall, London. Published by the Gay Humanist Group.

Every movement requires its handful of pioneers who are prepared to stand up and be counted — to be abused, […]

Harry Stopes-Roe was one of the most tireless and dedicated humanist campaigners of the 20th century. Son of the influential […]

At this nervous moment… when we have uncertainties about almost everything, it’s particularly necessary that we pool our determination, so […]

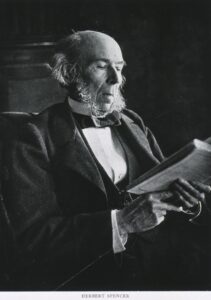

No one can be perfectly free till all are free; no one can be perfectly moral till all are moral; […]