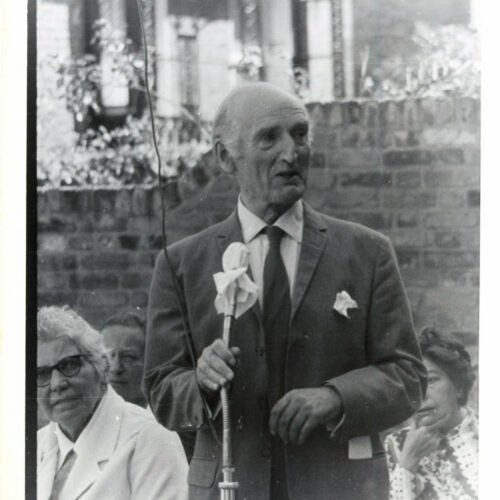

This article was written for Humanist News by Harold Blackham, who is viewed today as the architect of the modern humanist movement. Blackham had started his work for the movement at Stanton Coit‘s ‘Ethical Church‘, but went on to strip what was then known as the Ethical movement of its quasi-religious elements, reshaping it to reflect and promote human possibility on its own terms. Published in May 1988, the piece – reprinted in full below – marked 25 years since the formation of the British Humanist Association in 1963. Originally an umbrella organisation comprising the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK) and the Rationalist Press Association (now the Rationalist Association), the BHA marked a new departure for the self-identified humanist movement. In 1967, the Ethical Union would formally become the British Humanist Association and, fifty years later, Humanists UK.

Humanist News, May 1988

HAROLD BLACKHAM was the first Director of the BHA. When he retired in 1968, BHA records stated: “as founder and inspirer of post-war humanism, his contribution to the movement is unrivalled”. On the occasion of that movement’s 25th anniversary (and shortly after his own 85th!), he reminds us what he had in mind when he set out to change the old Ethical Union into the BHA…

The Ethical Movement was formed as a holding position in response to the widespread decline of religious belief since the 18th century in Europe and America. With the coming of democracy, there was a fear that people would be left to drift from their anchorage in social morality. Ethics was declared independent of religious or metaphysical beliefs. After a decade of work in this cause, I came to feel strongly that what was wanted and waited for, beyond this interim position, could not be a new religion, a revision of beliefs and doctrines; it had to be a life orientation that would focus a total human response to the world.

I came to feel strongly that what was wanted and waited for, beyond this interim position, could not be a new religion, a revision of beliefs and doctrines; it had to be a life orientation that would focus a total human response to the world.

That certainly required informed beliefs, in order to know what one had to respond to, and therefore how to take and tackle things. A sufficient decision on this might be highly general, and not issue in a set of doctrines or a creed. Indeed, the drift away from religion had been mainly a result of such relevant information. Moreover, human existence did not date from the 20th century. Opinions about the human condition were age-old, and had been divided in Western culture since the outset. Before Christ, there was a stark confrontation.

Primitive inscriptions in the Greek temple at Delphi had said: ‘Know yourself’ and ‘Nothing too much’; and the Greeks found this sufficient for the sum of wisdom. The original meaning was simply, ‘Know that you are a mortal man, not an immortal god, and therefore keep a low profile’. The other saying was a caution to the same effect. The main point, however, the permanent wisdom, implied a question: seek to discover what a human being is; and that was the general course followed by Greek philosophy, leading to different conclusions.

Inquiry or faith?

In stark contrast, it seems not to have occurred to the Hebrews that there was any question at issue. The Lord of Hosts gave them victory and dominion, on condition of exclusive loyalty and obedience. Eventually, through reflection on their experience as a people, the belief became established that the God of their covenant was the self-revealing Creator of all that is, and the Father of mankind. The response required to this manifestation of the divine order of the world to Israel, and through Israel to all humanity, was acknowledgement by all of absolute dependence, and the duty of exclusive loyalty and obedience. The will of God was the rule of life.

The openness of inquiry, with alternative possibilities; or the commitment of faith: here was a decision on the human condition early in European history. In the course of the inquiry initiated by the Greeks, there were different opinions that made advances and occasioned radical shifts, broaching problems that have made the history of philosophy.

The openness of inquiry, with alternative possibilities; or the commitment of faith: here was a decision on the human condition early in European history.

Two main mutually exclusive alternatives emerged as the unbridgeable cleavage: the first, that the human was identified within the organized material world of nature; the second, that the human was thought of as distinctively independent of the body, with which it could not be identified. In consequence, there was human sovereignty, the regnum hominis of Protagoras and the Sophists, or the divinely ordained world of Plato and the Stoics, in which the human role was prescribed and universal. There were thus three traditions, with continuity down to the present day: the humanism and empiricism of the regnum hominis; the Idealism of successive philosophies; and the Christianity which came out of Judaism and was given dominion by Rome.

A new beginning

I thought it was time to break clear of the ambivalence and confusions and opt boldly for the regnum hominis of Humanism; that we should identify ourselves with that particular tradition which had come down from the Greeks, kept underground during the long ascendancy of Christianity. It had come to the top with the awakening of Europe that was called the Enlightenment, at the end of the 18th century. We should possess those origins and that history as our own, and study it — without any sacred text.

I thought it was time to break clear of the ambivalence and confusions and opt boldly for the regnum hominis of Humanism; that we should identify ourselves with that particular tradition which had come down from the Greeks… We should possess those origins and that history as our own, and study it — without any sacred text.

In 1944 (I had become part-time secretary of the Ethical Union), I launched a quarterly journal, The Plain View, in place of The Ethical Societies’ Chronicle, and got WH Smith to distribute it, especially on mainline railway stations. The editorial of the first issue said:

“There is in immediate prospect a civilization that will be different in its assumptions and in its manifestations… from the Victorian age which fell into the last violent phases of its dissolution on the outbreak of the first world war. It is our deepest directive purpose in this review to help men and women of our time to come to a fully individualized consciousness of themselves in relation to this new age, and to form a true and detailed conception of the distinctiveness and scope of the civilization to be achieved.”

I had felt profoundly the gloom and doom of the interwar years, and latterly the helplessness of a generation that knew it was being dragged to the edge of an abyss. Some of us survived the catastrophe:

“We do not chiefly need, most of us, to be recalled to religion or to morality, but to be restored to the conditions of a happy affirmative life… The opportunity is offered by the new world which the surgery of events has made not powerless to be born… Civilization has been saved. But not the civilization we have known. It is the possibility of civilization that has been saved; the continuity, not the identity.”

Identifying Humanism

I quote this much from the first editorial, as a scrap of the documentary evidence of what I had in mind at the time, because one is apt to recall the past in the light of the present. I thought of Humanism, then as now, not as a set of doctrines, nor any kind of creed, but as an activity committed to public tasks set and shaped by the times, an application of ideals, universals of experience, in informed initiatives, developed in and through the particular experience they shape.

I thought of Humanism, then as now, not as a set of doctrines, nor any kind of creed, but as an activity committed to public tasks set and shaped by the times, an application of ideals, universals of experience, in informed initiatives, developed in and through the particular experience they shape.

What that would mean in practice, political and otherwise, could not easily be made clear. There was the difficulty of identifying a movement that was practical and general without being or becoming a lobby or pressure group tied to one particular objective. The tasks required for human survival have become clearer in specific terms since then, and the sanctions more realistic and effective.

What did become more definite, in working against and with religious bodies in the field of education in county schools after the 1944 Act, was the need for an open society as well as an open mind. Commitment to openness became a benchmark of Humanism. It cannot mean universal tolerance, and an open mind does not lack conviction. There are enemies. There are justified beliefs and disbeliefs. They are bound up with tasks and directives that are the primary imperatives.

What did become more definite… was the need for an open society as well as an open mind. Commitment to openness became a benchmark of Humanism.

Humanism has this determinative public dimension. Private life, on our assumptions, is less prescriptive, wide open to personal choice. There is always better and worse, but many forms of the good life. The summum bonum, chief good, is a vain quest in which ethics used to get bogged. The range of human interests is immense. Humanism in principle embraces them all. Religion, by contrast, can never be one thing among others. It is paramount or nothing. Humanism has been and is historical. It can be defined only by what it has and does put its hand to, with the reasons for it. It has this principle of vitality and growth within it.

There is no one who will deny the value and importance of truth, but how is it to be ascertained, […]

University College London was founded in 1826 as the University of London; the city’s first university, and a consciously secular […]

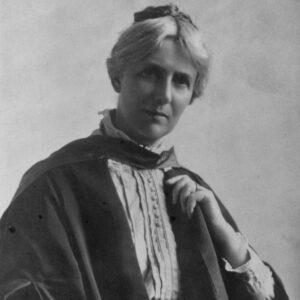

Millicent Mackenzie was a pioneering educationist and suffragist, who – alongside her husband, John Stuart Mackenzie – gave significant support […]

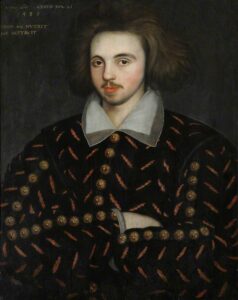

I count religion but a childish toy,And hold there is no sin but ignorance. Christopher Marlowe, The Jew of Malta, […]