What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult for each other?

George Eliot, Middlemarch (1871)

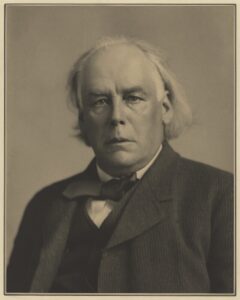

Mary Ann Evans (best known by her pen name, George Eliot) was one of the most celebrated novelists of the Victorian era, whose empathic realism has secured her reputation as one of the UK’s greatest writers. She was also a convinced humanist, whose capacity for sensitive observation and central belief in the power of human connection animated her life and fiction. Her writing was particularly influenced by the work of the French humanist Auguste Comte and his positivist school.

A freethinker in philosophy, she was also a brave defier of societal conventions, risking relationships and reputation to live openly outside of wedlock with George Henry Lewes. Oft quoted and devotedly read, Evans remains an inspiration to many today, and stands as a powerful example of the humanist values lived by many more Victorians than is often assumed.

Never to beat and bruise one’s wings against the inevitable but to throw the whole force of one’s soul towards the achievement of some possible better, is the brief heading that need never be changed, however often the chapter of more special rules may have to be re-written.

George Eliot in a letter to Clifford Allbutt, 30 December 1868

Mary Ann Evans was born on the Arbury Hall Estate in Nuneaton, of which her father was manager. Her mother, Christiana, died when Evans was sixteen and she later moved with her father to Coventry. There, she was introduced to the Brays and their Rosehill Circle: a vibrant group of freethinkers and reformers, who strengthened Evans’ growing religious doubts, and her confidence in dissenting openly from her devoutly Christian upbringing. Her decision to stop attending church led to painful conflict with her father, though the two reconciled (on condition that she maintain outward respectability through church attendance) and she cared for him until his death in 1849.

Following her father’s death, freed from the responsibilities of keeping house, Evans spent the winter in Geneva, where she lived with the family of Swiss artist François D’Albert Durade. It was to Durade she would later write of her ‘rooted conviction’ that ‘the proper sphere of all our highest emotions are our struggling fellow-men and this earthly existence:’ a humanist philosophy exemplified in her life and writing.

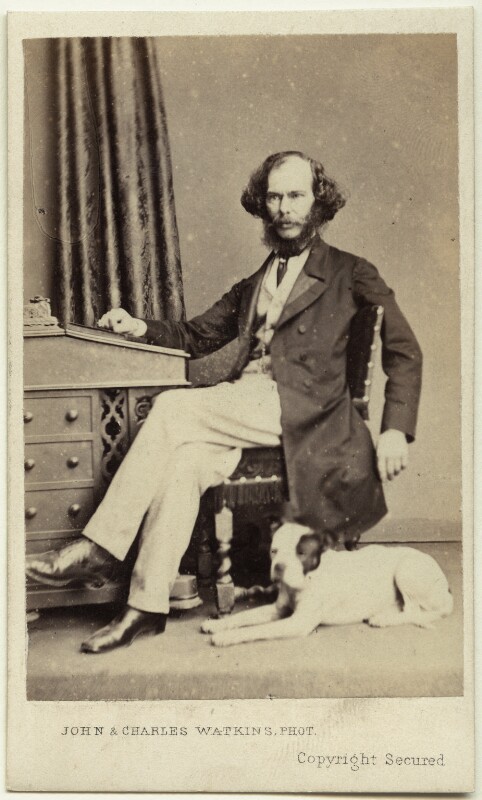

In 1851, Evans moved to London and became Assistant Editor of The Westminster Review. In London, and the progressive literary circle she now inhabited, Evans socialised with many of the leading thinkers of the time, including Herbert Spencer, Harriet Martineau, and George Henry Lewes. She and Lewes entered into an unconventional but devoted partnership, considered scandalous by many given their cohabitation, and Lewes’ continuing marriage to his first wife. Evans suffered significantly from the hostility of Lewes’ friends towards her, and that of her own, including those who were otherwise progressive in attitudes. Nevertheless, the couple considered themselves married, and remained happily together until Lewes’ death nearly a quarter of a century later.

Prior to her career as a novelist, Evans produced some significant works of translation, reflecting and developing her own eloquent rationalism, and offering insight into her philosophical interests. These included German philosophers David Strauss (Life of Jesus, 1846), and Ludwig Feuerbach (Essence of Christianity, 1854), as well as Baruch Spinoza’s Ethics (completed in 1856, but not published). Strauss argued that the gospels were mainly myth, while Ludwig Feuerbach was a humanist and critic of religion who suggested that human goodness sprang from human nature alone. Spinoza espoused a kind of pantheistic deism. A critical, rationalist perspective, and an understanding of the possibility and responsibility of humankind, were developed in these works, and found expression in Evans’ own literature.

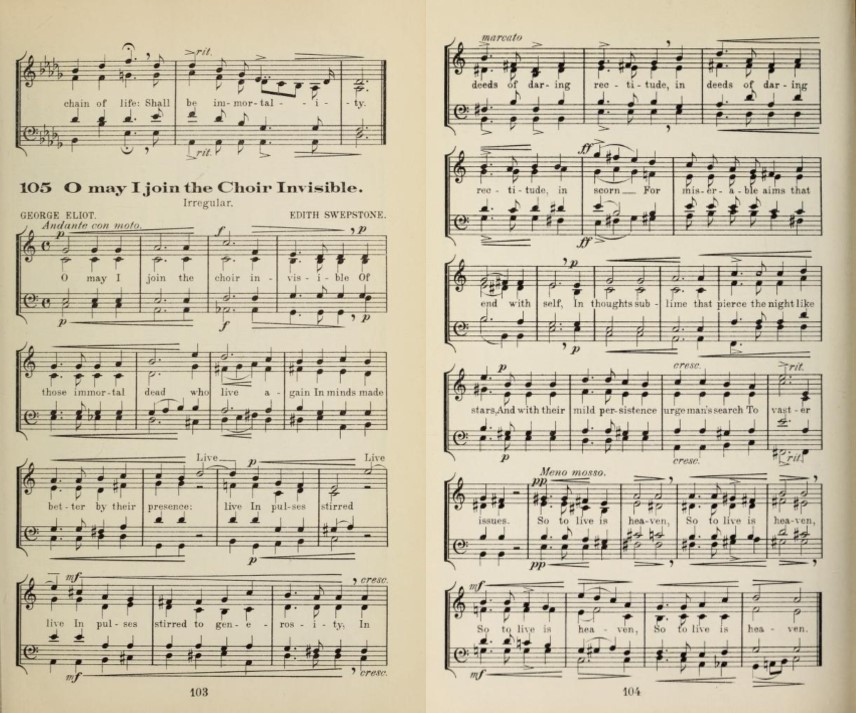

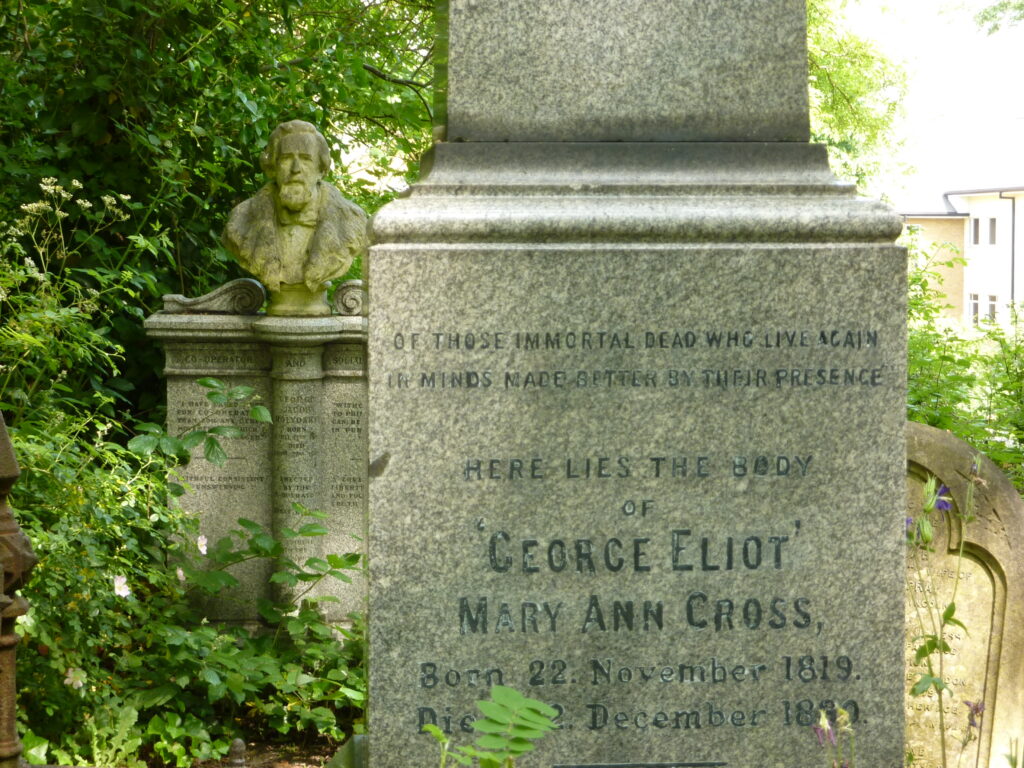

Under the pseudonym George Eliot, Evans wrote a total of seven novels. Her first, Adam Bede, was published in 1859; her last, Daniel Deronda, in 1876. In addition to novels, she penned essays and poems. One of her best known poems, ‘O May I Join the Choir Invisible’, was set to music and used regularly in meetings of various ethical societies. The poem, centring on the human capacity to improve the world for others, makes a powerful case for the only kind of afterlife Evans herself believed in.

Evans’ novels were rich with empathy, and concerned with life as it was lived and experienced by the full spectrum of humanity. Her careful, non-judgemental observation lent realism and relatability, and the inner lives and personal turmoils of her characters drew on Evans’ own struggles – with depression, isolation, and illness. Her works examined the sense of personal duty amidst society’s conventions and expectations, not least for women, as well as the quiet heroism of the ordinary individual, seeking to improve the world for others. As she wrote in Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life (1871):

The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts: and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

Art and human relationships were central to this vision, and Evans’ own life and writings exemplified a striving for connection. In a letter to educationist, artist, feminist, and co-founder of Girton College Barbara Bodichon, Evans wrote:

It is hard to believe…that anything is “worth while” unless there is some eye to kindle in common with our own, some brief word uttered now and then to imply that what is infinitely precious to us is precious alike to another mind.

George Henry Lewes was one other mind whose support and sympathies buoyed Evans, and secured the practical details of living which facilitated her writing. The pair bought a home near Regent’s Park, London in 1863, where their Sunday afternoon gatherings drew many more lively and like minded friends around them. Lewes died in 1878, and Evans later married a longtime friend John Walter Cross. Tragically, within a year of marriage and aged just 61, Evans became ill with a throat infection, compounding a pre-existing kidney condition, and died on 22 December 1880. She was buried in Highgate Cemetery, alongside Lewes.

So shall I join the choir invisible

Whose music is the gladness of the world.

Our dead are never dead to us, until we have forgotten them.

George Eliot, Adam Bede (1859)

In The Mill on the Floss, Evans wrote of ‘a life vivid and intense enough to have created a wide fellow-feeling with all that is human’. Through her writing, her friendships, and her legacy, she can certainly be said to have lived one. Evans believed in nothing beyond death, and was driven to promote good deeds and fellow feeling not by the hope of heavenly reward, but by a reasoned sense of duty, and a heartfelt compassion for humankind. Hers was a humanism often left out of biographies, which frequently acknowledge her loss of faith, but not the positive affirmation of life and its meaning which continued to animate her own life, and underpin her prose. Like freethinkers before and since, she rejected the confines of supposed respectability where they conflicted with her own conscience, blazing a trail for those others whose moral convictions led them to rebel and reform. And, as Lord Acton wrote:

as the emblem of a generation distracted between the intense need of believing and the difficulty of belief, [the books of George Eliot] will live to the last syllable of recorded time.

Lord John Acton, ‘George Eliot’s Life’ in The Nineteenth Century, March 1885, and reprinted in Historical Essays and Studies (1907)

Mary Ann Evans is one of four humanist women featured in a set of Humanist Heritage stories and activities for schools: Think for Yourself, Act for Everyone.

The National Secular Society is a campaigning organisation, founded in 1866 to champion the principles of secularism and the separation […]

To summarise why I have become a rationalist is a difficult task for one not educated in formal writing, but […]

The Humanist Broadcasting Council was established in 1959, in consultation with the BBC, to advocate for the inclusion of humanist […]

Her beautiful life, her truth, her unwearied charities, proceeded from her own heart. They were not inspired by any thought […]