Living in a house beautifully situated on the outskirts of Coventry, they used to spend their lives in philosophical speculations, philanthropy, and pleasant social hospitality…

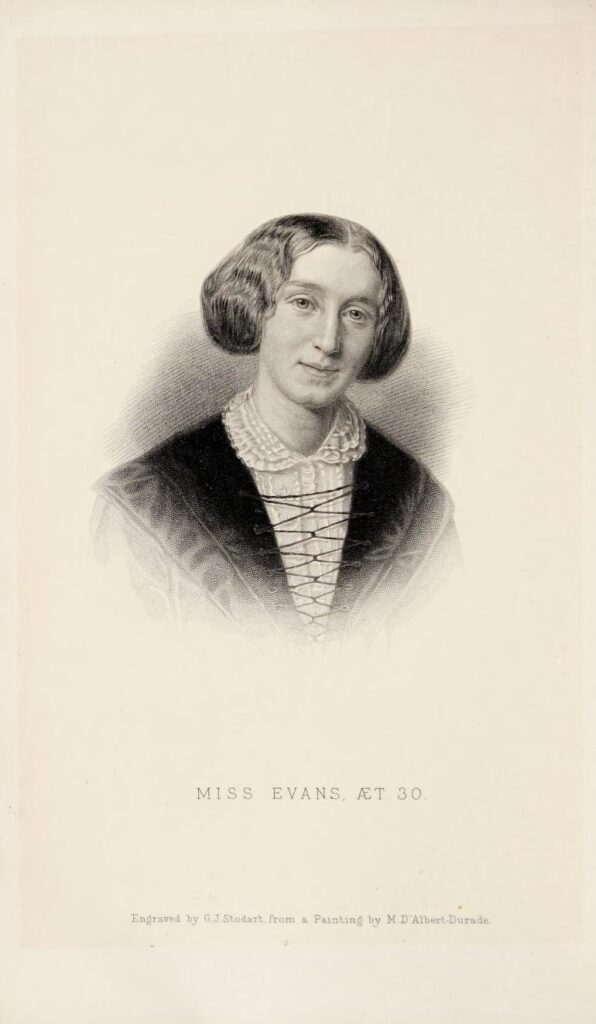

Mathilde Blind, George Eliot, 1883

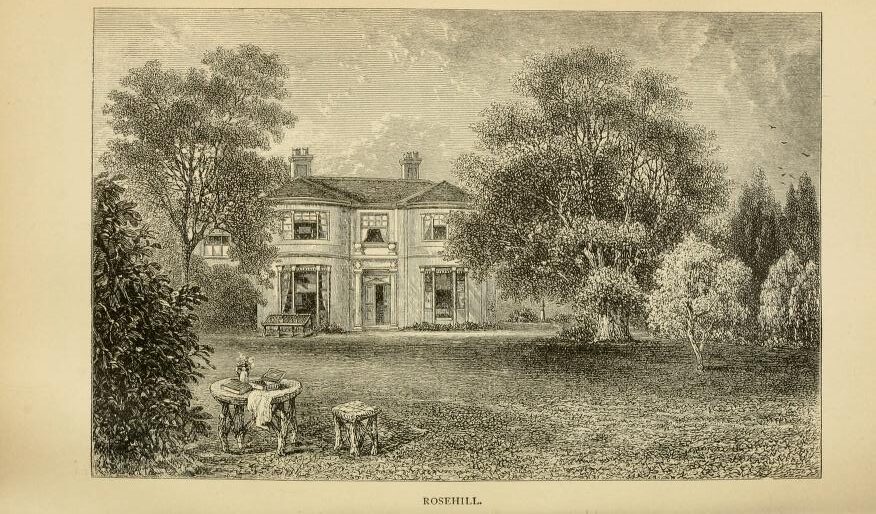

The Rosehill circle was a group of friends and associates who gathered at ‘Rosehill’, Coventry, the home of Charles and Cara Bray. Rosehill became established as a place for open debate, discussion, and intellectual exchange, and was a formative influence on Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot). Peopled with liberals and freethinkers, the Rosehill circle openly discussed religious, philosophical, and political subjects, and welcomed many radicals and reformers as visitors. It provided, like similar settings in other provincial towns and cities, a place for the exposition of humanist ideas, sequestered away from the easily scandalised Victorian society outside.

My whole soul has been engrossed in the most interesting of all inquiries for the last few days and to what result my thoughts may lead I know not – possibly to one that will startle you, but my only desire is to know the truth, my only fear to cling to error.

Marian Evans to Maria Lewis, 1841

The Rosehill circle centred on the Brays: wealthy ribbon manufacturer and social reformer Charles, and his wife Caroline (née Hennell; known as Cara), a writer and artist. Charles Bray was a freethinker, who rejected all denominational religion, was inspired by Owenite secularism, and advocated for a national system of non-sectarian education. He helped to found, in 1835, the Coventry Mechanics’ Institute, and the Coventry Labourers’ and Artisans’ Co-operative Society in 1843. Bray bought Rosehill in 1840, and lived there with Cara and a regular stream of guests until 1857. Aside from the Brays and their circle, Coventry had an established tradition of liberalism and radical politics. During the 1840s, there was still an active socialist group, and a number of freethought organisations. George Jacob Holyoake wrote that

[religious] Infidelity in Coventry… is not a ricketty, but a fine-grown boy. More is done than is recorded, and liberal views extend farther than is supposed.

Cara Bray came from a Unitarian family, and was less sceptical in matters of religion than her husband. Slightly dismayed by his antagonism towards it, she encouraged her brother, Charles Christian Hennell, to write a work exploring their faith. The resulting book, An Inquiry Concerning the Origin of Christianity (1838), refuted the miraculous claims of the Bible, highlighted the issues presented by its multiple authorship, and ultimately suggested that it should be studied just as any other human-made text would be. Nevertheless, he retained a reverence for the example of Jesus, and for the value of the Bible itself. Cara maintained a similar reverence, albeit within the decidedly unorthodox setting of Rosehill. She was a writer of children’s books and a defender of animals; founder of the Coventry branch of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1874, and author of Our Duty to Animals three years earlier.

The Brays’ home was quickly established as a haven for freethought, open discussion, and humanitarian values. Rosehill was commonly visited by travelling intellectuals and social reformers, including Robert Owen, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and William Johnson Fox, then minister of the Unitarian congregation which would become the humanist South Place Ethical Society. Most famously, Rosehill regularly welcomed Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), who lived nearby and became a close and admired friend of the Brays.

The circle at Rosehill has been noted by many biographers as playing a significant role in strengthening Evans’ resolve in her own religious scepticism. First visiting Rosehill in November 1841, Evans found a circle who encouraged honest enquiry into religion, open discussion of literature and philosophy, and the active pursuit of progressive social reform. The Brays in turn were impressed by Evans’ freedom of thought, erudition, and openness. She stopped going to church in January 1842, causing a significant rift in her relationship with her father, throwing into harsh relief the dangers of outwardly rejecting religion, but setting decisively in motion her embrace of a humanist worldview. As Mathilde Blind would later write:

In intercourse with them she was able freely to open her mind, their enlightened views helping her in this crisis of her spiritual life; and she found it an intense relief to feel no longer bound to reconcile her moral and intellectual perceptions with a particular form of worship.

Similar circles to that at Rosehill existed in provincial towns and cities elsewhere, which nurtured other influential freethinkers throughout the 19th century. Liberal Unitarian communities in Norwich and London played a significant role in the lives of Harriet Martineau and William Johnson Fox respectively. Centres of freethought like those in Coventry, Norwich, and at South Place fostered the freedom to express religious doubt, dissent from traditional gender roles, and generally experience some relief from the strictures of Victorian society. All three placed emphasis on the duty of enquiry and the absence of creed which appealed to the freethinking and curious.

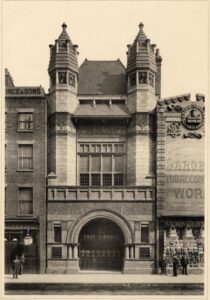

Bishopsgate Institute was built ‘for the benefit of the public’ in 1894, intended to provide opportunities for education and recreation […]

Josiah Gimson was the most prosperous of the 19th century secularists in Leicester, and the main force behind the building […]

No creative thinker has so governed… my mind as the French genius who framed the maxim – “Love for principle, […]

Julia Huxley was a feminist and freethinker, who profoundly influenced a generation of girls who attended the school she founded […]