Free thought means fearless thought. It is not deterred by legal penalties, nor by spiritual consequences. Dissent from the Bible does not alarm the true investigator, who takes truth for authority not authority for truth.

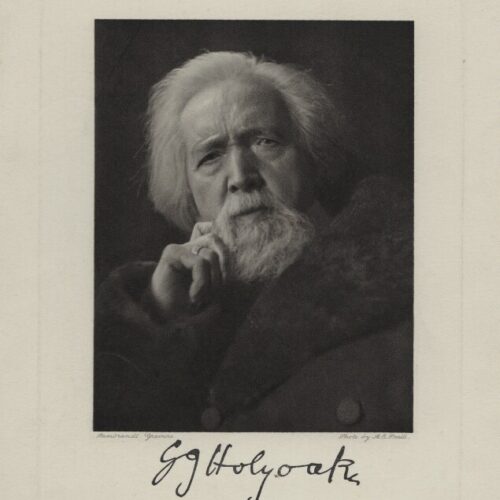

George Jacob Holyoake was a writer, editor, cooperator, and coiner of the word ‘secularism’. A follower of Robert Owen, he was a major proponent of socialist Owenite principles, including the idea of a ‘rational religion’ entirely removed from any notion of a god. He became a leader in the secularist movement, as well as a staunch advocate of the values of cooperation, freedom of the press, and equality in all areas of society. His daughter, Emilie Ashurst Holyoake, went on to take an active role in the humanist Ethical movement, and Holyoake himself worked in support of the ethical societies.

As creator of a definition of ‘secularism’ largely indistinguishable from that of humanism today, as well as in his own life and work, Holyoake remains a significant figure in the history of the humanist movement.

Holyoake was born on 13 April 1817 in Birmingham, where he followed his father into the whitesmithing trade. As a young man he was much influenced by the socialist writings of Robert Owen. He endeavoured to become a teacher but found it difficult to progress due to his socialist views.

He joined the Birmingham Reform League in 1831 and the Chartists in 1832. In 1840 Holyoake decided to become a ‘socialist missionary’ and follower of Robert Owen, moving to Worcester to become a full-time socialist lecturer. Among his fellow lecturers was Charles Southwell, who helped establish an atheist periodical The Oracle of Reason in 1841. As editor, Southwell was soon tried for blasphemy and sent to gaol in Bristol.

Although Holyoake was not an atheist at this time, his friendship with Southwell, and fury at the injustice he thought he had suffered, led him to volunteer as editor of The Oracle during Southwell’s absence. He soon lost whatever remnant of Christianity remained.

In May 1842 Holyoake was on his way to visit Southwell in gaol when he stopped in Cheltenham to give a lecture. In reply to a question he suggested that ‘the Deity should be put on half-pay’ and added that ‘I flee the Bible as a viper, and revolt at the touch of a Christian.’ His reward was six months’ imprisonment for blasphemy in Gloucester.

While in prison Holyoake was visited by Richard Carlile which greatly amused him as he had been informed by the authorities that Carlile had suffered a ghastly death recanting all his principles before he died. The prison authorities made successive, unsuccessful attempts to convert Holyoake to Christianity.

Holyoake emerged from prison a radical hero, settling in London and founding and editing various progressive newspapers, most notably The Reasoner (1846-50). He did much to secure the freedom of a cheap press, available to all, although his struggles against “the taxes on knowledge” came at a significant cost in fines.

In 1845 Holyoake presided at the opening of the Rochdale Co-operative Store which served as a successful model imitated by subsequent co-operative societies and was a trigger to the rapid growth of the co-operative movement. He became co-operation’s leading champion and authority. The Co-operative Union still occupies Holyoake House, Manchester built in his memory and opened in 1911.

By 1851 Holyoake began to use the word ‘secularist’ to describe himself and his followers. He defined secularism as:

…that which seeks the development of the physical, moral, and intellectual nature of man to the highest possible point, as the immediate duty of life – which inculcates the practical sufficiency of natural morality apart from Atheism, Theism or the Bible – which selects as its methods of procedure the promotion of human improvement by material means, and proposes these positive agreements as the common bond of union, to all who would regulate life by reason and ennoble it by service.

Holyoake’s view of secularism was thus much akin to modern definitions of humanism and is broader than just atheism. Holyoake himself regarded the term atheism as too negative; he was looking for something more positive and fulfilling.

Holyoake continued to lecture throughout the country and as time passed his views began to mellow. By the late 1850s his leadership of the secularist movement was being challenged by the younger, energetic Charles Bradlaugh who was more eloquent, more radical, and a better organiser. Apart from this Holyoake had modified his view of Christianity, was to be increasingly impressed by the work of Christian socialists, and had lost the militant edge which had characterised his early days.

In 1858 Bradlaugh was elected president of the London Secular Society, but divisions arose in 1877 when Holyoake opposed Bradlaugh and Besant’s publication of Fruits of Philosophy, and helped to found the British Secular Union as a rival to the National Secular Society.

Holyoake later rejoined the National Secular Society after Bradlaugh’s death and the demise of the British Secular Union. In his later years he also took a zealous part in the foundation of the Rationalist Press Association (RPA) of which he was the first Chairman.

Holyoake died in Brighton on 22 January 1906.

Holyoake’s contribution to the rise and success of secularism and progressive humanist ideas is immense. His long life spanned the Chartists, the growth of cooperation, the struggle for a free press, and Bradlaugh’s campaigns to enter Parliament. He fought for the rights of women, political reform, arbitration, education, and other progressive reforms, and provides – through his own person and that of his daughter – a direct link between the Victorian secularist movement and the birth of organised humanism.

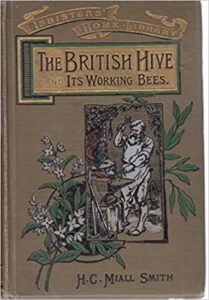

Hilda Caroline Miall-Smith was a teacher and activist, a graduate of University College London, and a member of the London […]

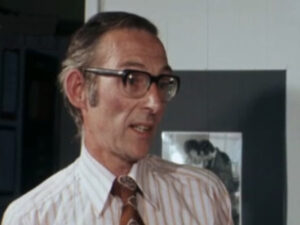

Belfast-born Jack McDowell was an activist, educator, politician, and atheist, whose humanism was evident in a lifetime of work for […]

If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, […]

Auguste Comte was a French writer, philosopher, and social scientist, whose theory of positivism was a significant influence on the […]