If living does not give value, wisdom and meaning to life, then there is no sense in living at all.

W.E.B. Du Bois, The Autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois (1968)

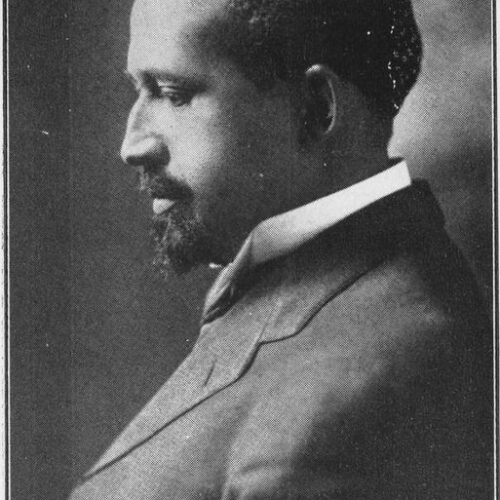

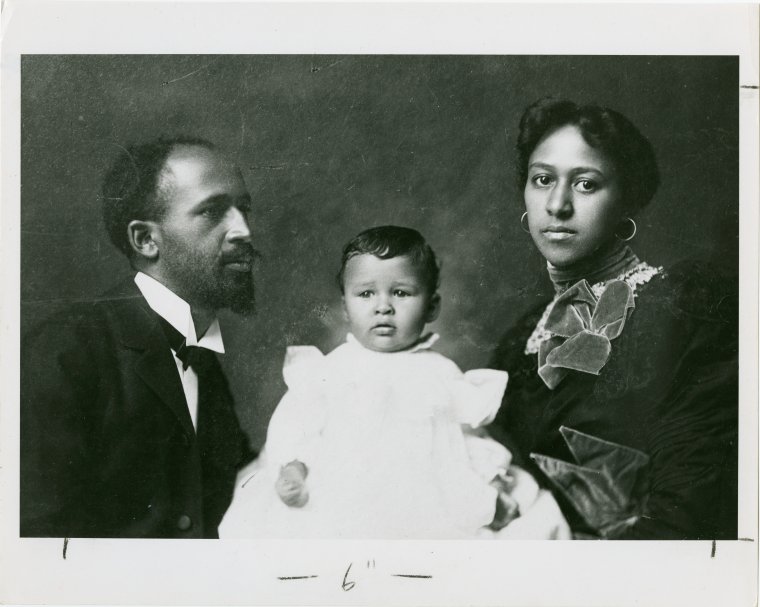

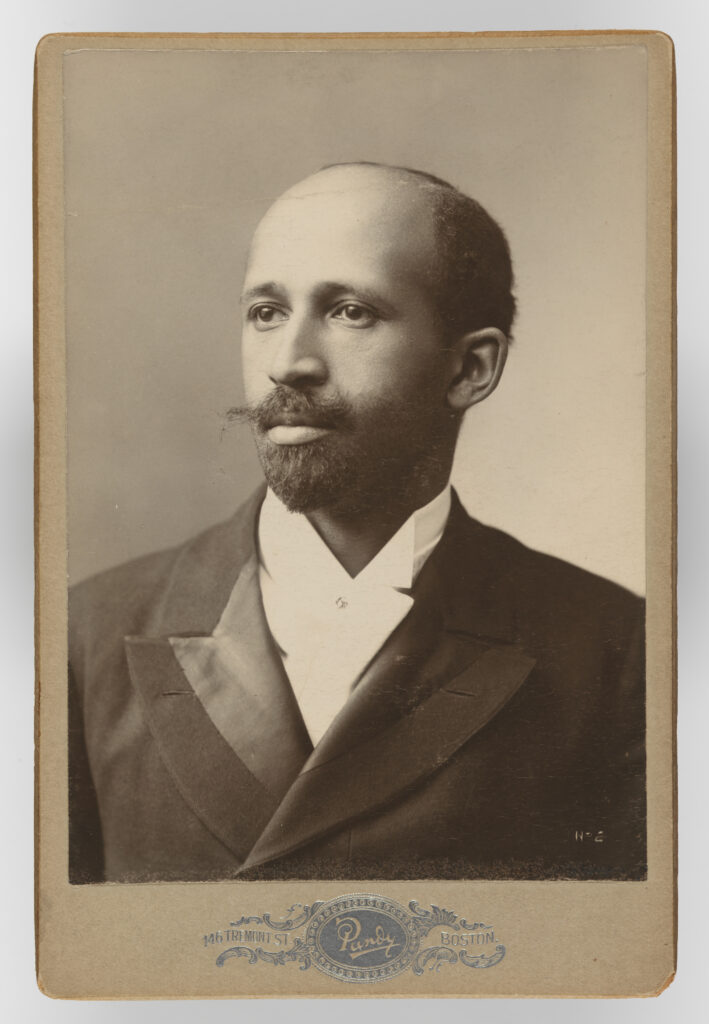

W.E.B. Du Bois was one of the most prominent American intellectuals, and foremost civil rights activists, of the 20th century: a sociologist, historian, journalist, philosopher, author, pan-Africanist, and co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Du Bois was also closely associated with leading figures of the Ethical movement, and deeply influenced by the First Universal Races Congress, organised by Du Bois’ close friend, Gustav Spiller. Du Bois himself rejected religion, living instead by a humanist philosophy rooted in reason, empathy, and active reform.

…to each according to his need, from each according to his ability. For this I will work as long as I live. And I still live.

W.E.B. Du Bois, The Autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois (1968)

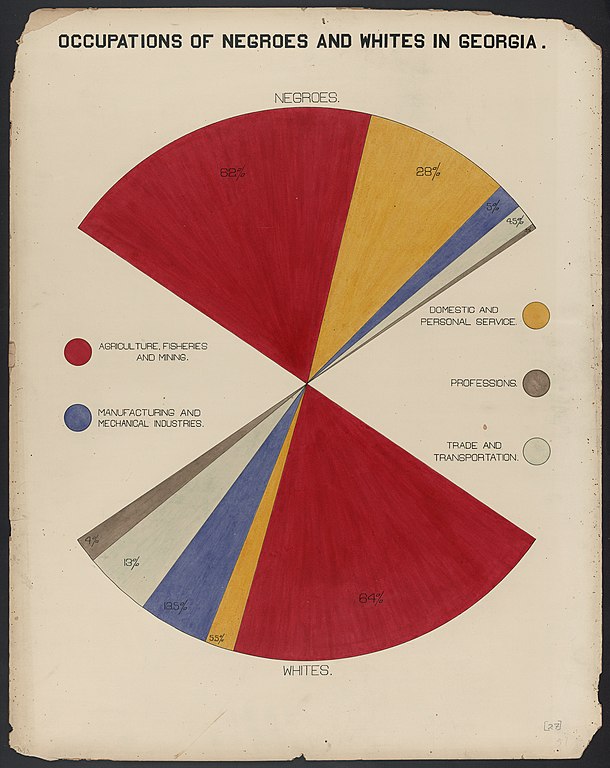

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts on 23 February 1868. He was educated at Fisk University, Tennessee, the University of Berlin, and Harvard, becoming, in 1895, the first African American to receive a doctorate from Harvard University. It was in Germany, he wrote, that he ‘became a freethinker’, and his conscious break with organised religion was hastened when, later, ‘a hidebound old deacon inveighed against dancing’. His life, academic and activist, was dedicated to efforts for racial equality, through organisation, education, and cooperation, motivated by a profound sense of injustice and a scholarly devotion to knowledge effectively applied: notably, in using science and history to refute myths of racial inferiority, and empower America’s black population.

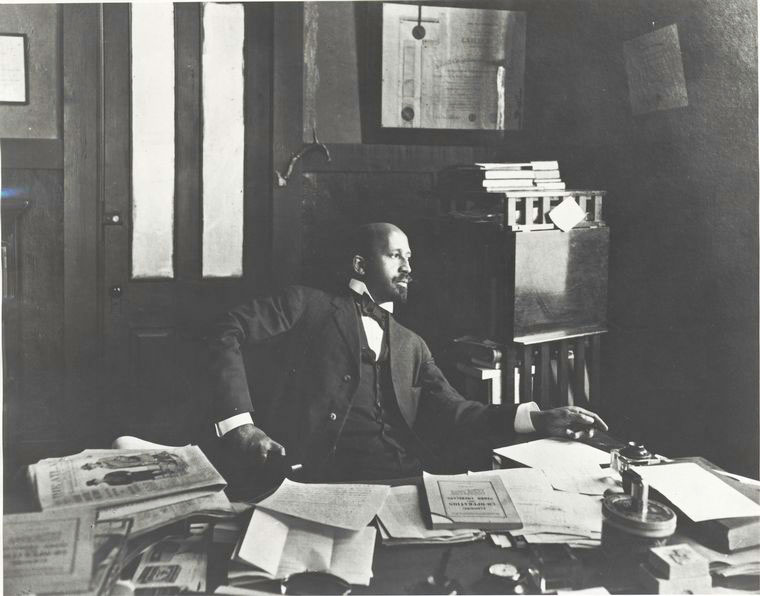

For thirteen years, 1897-1910, Du Bois taught history and economics, and developed the sociology programme, at the University of Atlanta. These, he wrote, were ‘years of great spiritual upturning, of the making and unmaking of ideals, of hard work and hard play’:

Here I found myself. I lost most of my mannerisms. I grew more broadly human, made my closest and most holy friendships, and studied human beings. I became widely acquainted with the real condition of my people. I realised the terrific odds which faced them.

In Atlanta, he wrote The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and John Brown (1909), and founded two literary magazines. In 1905, Du Bois founded the Niagara Movement: a group of radical African American scholars and professionals. In 1909, he co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Among his fellow founders was Henry Moskowitz, Associate Leader of the New York Society for Ethical Culture. It was America’s grave racial inequality, and finding the tools to fight it, which would remain the focus of his life and work. The ‘color line’, he wrote, was ‘not only the most pressing social question of the modern world’ but ‘an ethical question that confronts every religion and every conscience’. In 1940’s Dusk of Dawn, he said:

My life had its significance and its only deep significance because it was part of a Problem; but that problem was, as I continue to think, the central problem of the greatest of the world’s democracies and so the Problem of the future world. The problem of the future world is the charting, by means of intelligent reason, of a path not simply through the resistances of physical force, but through the vaster and far more intricate jungle of ideas conditioned on unconscious and subconscious reflexes of living things; on blind unreason and often irresistible urges of sensitive matter; of which the concept of race is today one of the most unyielding and threatening.

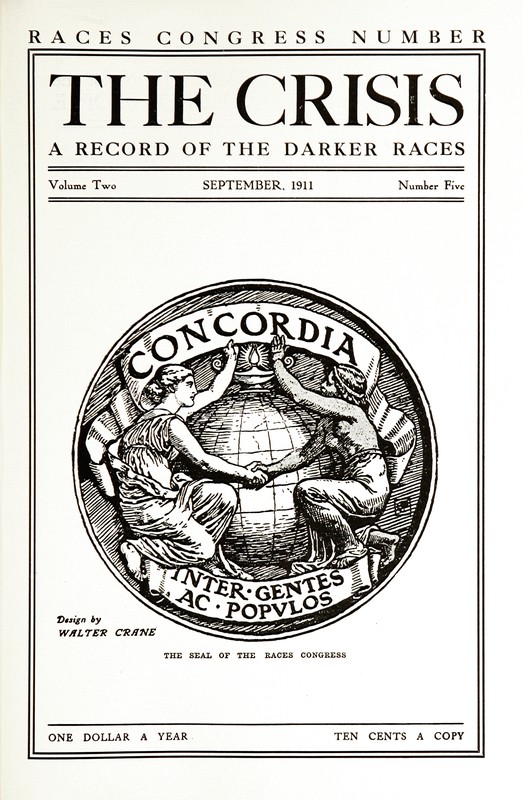

In 1910, Du Bois left Atlanta for New York, becoming the NAACP’s Director of Publicity and Research. In the same year, he established its newspaper, The Crisis: ‘an independent organ leading a liberal organisation toward radical reform.’ Alongside writing and lecturing, Du Bois continued to edit The Crisis and work actively for the NAACP for just under 25 years.

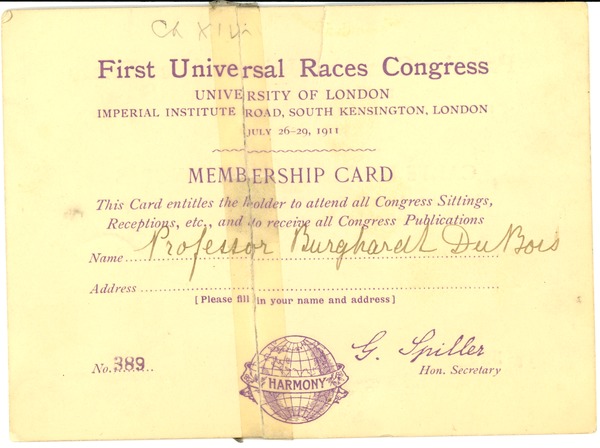

In 1911, Du Bois attended the First Universal Races Congress, organised by Gustav Spiller and initiated by leading figures within the Ethical movement. He would later write:

The Races Congress in 1911 would have marked an epoch in the racial history of the world if it had not been for the World War. Felix Adler and I were made secretaries of the American section of the Congress in London. It was a great and inspiring occasion bringing together representatives of numerous ethnic and cultural groups and bringing new and frank conceptions of scientific bases of racial and social relations of people.

The use of science and shared knowledge to dispel prejudice and increase a sense of human unity was at the heart of the Congress, and closely aligned with Du Bois’ own ideals. As a historian and social scientist, he believed in history and sociology as tools to educate, empower, and reform, particularly valuable in challenging oppressive power structures and addressing the subjugation of African Americans. The hope of subsequent congresses was shattered by the outbreak of the First World War, but the idealism of the Congress and its organisers – who sought international cooperation and understanding – found later expression in efforts toward the United Nations. Du Bois himself went on to play a leading role in pacifist bodies such as the Peace Information Center, and its successor the American Peace Crusade. In 1945, Du Bois served as a consultant to the UN founding convention, and in 1947 published An Appeal to the World: A Statement on the Denial of Human Rights to Minorities in the Case of Citizens of Negro Descent in the United States of America and an Appeal to the United Nations for Redress.

Epitomising again Du Bois’ central belief in cooperation for individual empowerment and radical reform, he became a driving force in the Pan-Africanist movement. In 1900, Du Bois attended the precursor to the Pan-African Congresses, the Pan-African Conference, in London, and subsequently became a leading figure in the global movement. He helped to organise the Congresses of 1919, 1921, 1923, and 1927, during which he met Harold Laski, H.G. Wells, and almost Ramsay MacDonald, who ‘had promised to speak to us but was hindered by the sudden opening of the campaign which eventually made him prime minister of England.’

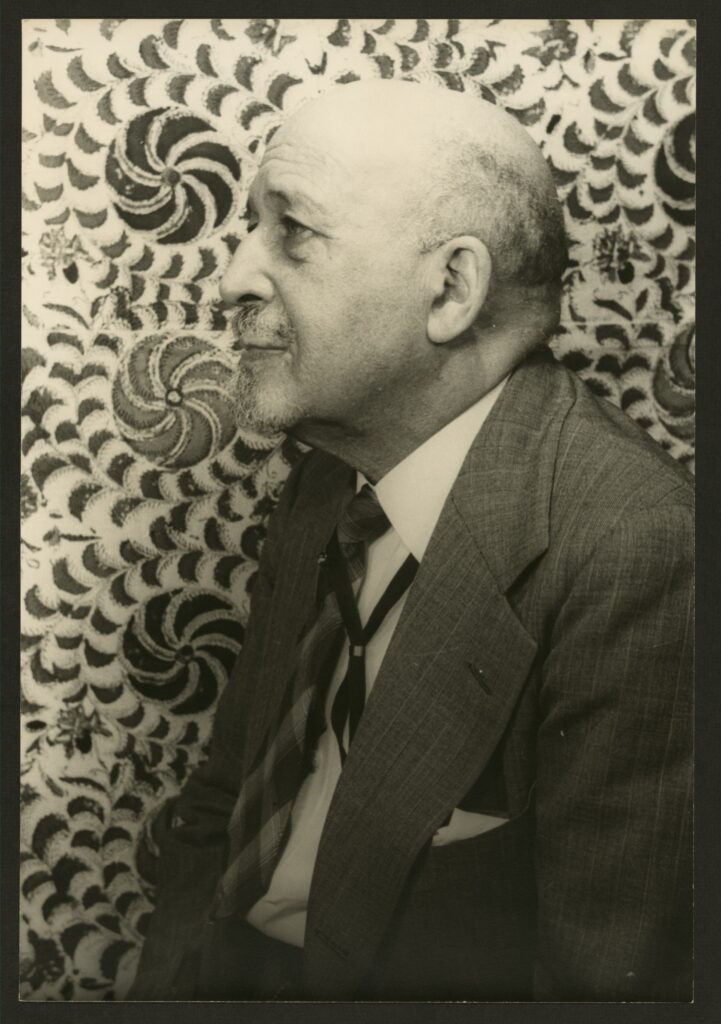

In his autobiography, published posthumously in 1968, Du Bois stated repeatedly his rejection of ‘Christian dogma’. He despised the hypocrisy of religious bodies which had sanctioned slavery, and enforced racial division and discrimination, including by refusing membership to African Americans. ‘From my 30th year on’, he wrote, ‘I have increasingly regarded the church as an institution which defended such evils as slavery, color caste, exploitation of labor and war.’ Perhaps most unequivocally, in describing the Soviet Union he emphasised both the virtue of secular education, and the personal impossibility of religious belief. He wrote:

…the Soviet Union does not allow any church of any kind to interfere with education, and religion is not taught in the public schools. It seems to me that this is the greatest gift of the Russian Revolution to the modern world. Most educated modern men no longer believe in religious dogma. If questioned they will usually resort to double-talk before admitting the fact. But who today actually believes that this world is ruled and directed by a benevolent person of great power who, on humble appeal, will change the course of events at our request? Who believes in miracles? Many folk follow religious ceremonies and services; and allow their children to learn fairy tales and so-called religious truth, which in time the children come to recognize as conventional lies told by their parents and teachers for the children’s good. One can hardly exaggerate the moral disaster of this custom.

Du Bois believed in acting morally and working for radical change, guided by values of reason and compassion. In his rejection of traditional religion, and his statement that he ‘above all believed in work, systematic and tireless,’ Du Bois echoed the belief in ‘deed, not creed’ of his co-Secretary to the Universal Races Congress, Felix Adler, and the foundational ideal of the Ethical movement. Du Bois himself wrote that ‘there is no Dream but Deed’.

In 1961, Du Bois accepted an invitation from Kwame Nkrumah to move to Ghana, and two years later became a citizen. He died in Accra on 27 August 1963, at peace with the end of life. In the last pages of his autobiography he had written:

…we know that being dead, our Happiness is a fine and finished thing and that ten, a hundred, and a thousand years, we shall lie at rest… It is the end and without ends there can be no beginnings. Its finality we must not falsify… I have lived a good and full life. I have finished my course.

Nothing new, no time-saving devices, simply old time-glorified methods of delving for Truth, and searching out the hidden beauties of life, and learning the good of living.

W.E.B. Du Bois, The Autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois (1968)

Du Bois’ diverse career as intellectual and activist was underpinned by a central concern for racial equality, human opportunity, and an honest approach to history. His rejection of religion made him no less committed to his fellow humans, instead securing his belief in the vital role of the individual in giving meaning to life, and in improving it for – and with – others. Those who knew Du Bois recalled him not only as a formidable scholar and activist, but also as an amiable friend and colleague. Horace Bumstead, who recruited Du Bois to Atlanta University, wrote that ‘to his fellow teachers… he brought joy, for though often looked upon in the outside world as a pessimist, he was about the jolliest member of our Faculty’.

In a speech delivered at Carnegie Hall in New York City in 1968, scarcely six weeks before his assassination, Martin Luther King, Jr. echoed Bumstead, noting:

It is axiomatic that he will be remembered for his scholarly contributions and organisational attainments. These monuments are imperishable. But there were human qualities less immediately visible that are no less imperishable.

He went on:

Dr. Du Bois has left us but has not died. The spirit of freedom is not buried in the grave of the valiant. He will be with us when we go to Washington in April to demand our right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness… In conclusion let me say that Dr. Du Bois’ greatest virtue was his committed empathy with all the oppressed and his divine dissatisfaction with all forms of injustice.

W.E.B. Du Bois Papers, 1803-1999 at the University of Massachusetts

The Crisis, Races Congress Number, September 1911 at the Modernist Journals Project

Honoring Dr Du Bois by Martin Luther King, Jr.

Thomas Henry Huxley was a man of science, a biologist, and educator. He helped to transform scientific study into a […]

Belief in the power of man to choose his direction of change: this is the creed of the future, and […]

I am a feminist, a rebel, and a suffragist – a believer, therefore, in sex-equality and militant action. I desire […]

University College London was founded in 1826 as the University of London; the city’s first university, and a consciously secular […]