More science is needed, more interchange and more co-ordination. Act to that end. This is my philosophy of action; this is my philosophy of myself as a living part of Man… This is how I am living and how I hope to live to my end.

H. G. Wells, I Believe (1940)

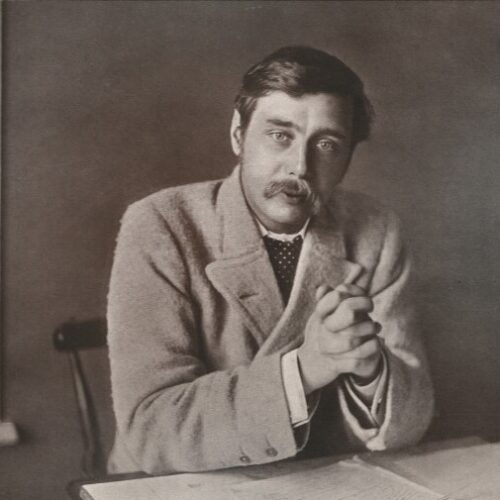

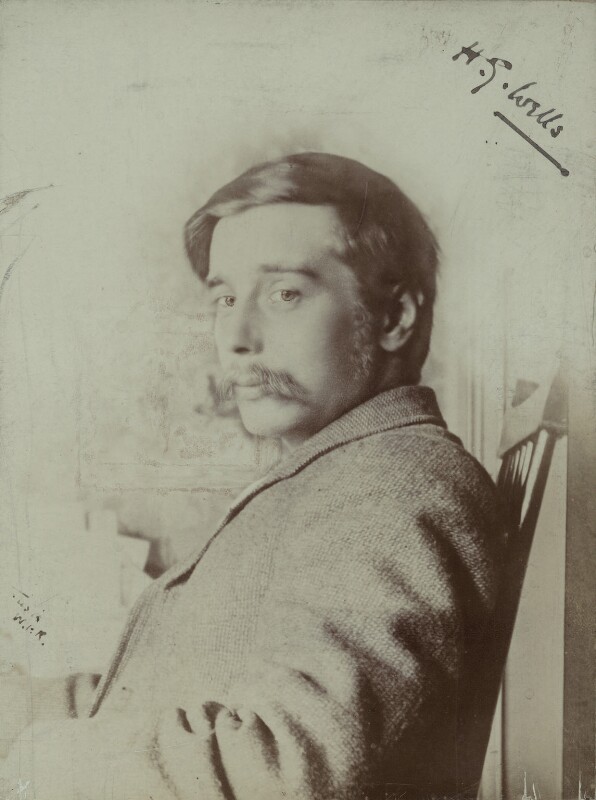

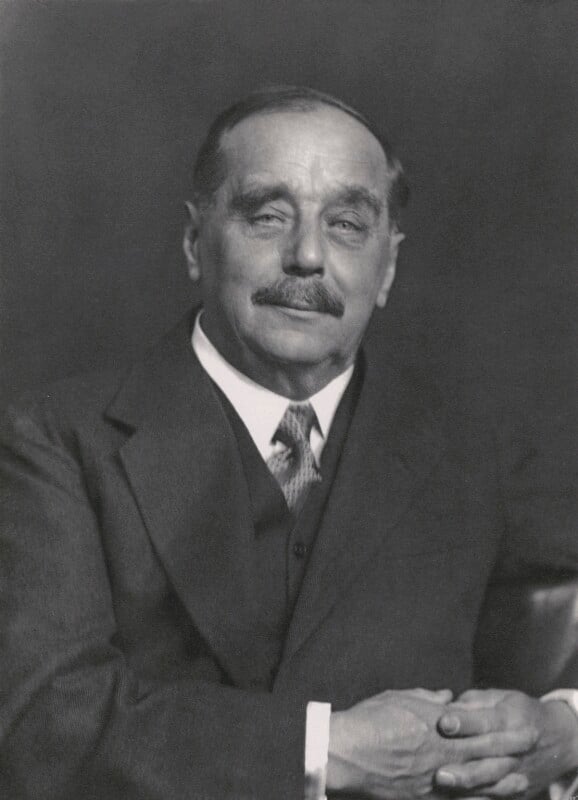

As a novelist, visionary, and public intellectual, Herbert George Wells was one of the 20th century’s most influential writers, and an outstanding humanist. Born on 21 September 1866 in modest circumstances in Bromley, Kent, Wells narrowly avoided a life of penury and obscurity in the drapery trade his mother planned for him. He studied at the Normal School of Science at South Kensington (now the Royal College of Science and part of the University of London) under T. H. Huxley, and taught for a while, before being able to earn a living as a writer.

His first published writing, called scientific romances at the time, is now known as science fiction. The best of these works, The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897) and The War of the Worlds (1898) remain classics in their field to this day. After the scientific romances, Wells moved on to novels about life, the best of which were Kipps (1905), Tono-Bungay (1908), an account of unrestrained capitalism, Ann Veronica, (1909), The History of Mr Polly (1910), and The New Machiavelli (1911). These novels can be read as perceptive stories about human interaction and for the specific insights into the mores of Edwardian England. Ann Veronica gave voice to a whole new outlook with respect to gender relations. Most ‘new woman’ novels of the time had the main character ending up making the right choices, or paying for making the wrong ones. But Ann Veronica made her own choices. They weren’t always good decisions, but they were always hers. This had not happened before. Dora Russell was one who remembered that Ann Veronica was the book that spoke to her generation.

Common wisdom says that, after these early works, what followed amounted to a slow decline. But the different challenges of the 21st century have cast new light on Wells’ value as a public intellectual. Central to his outlook was the seriousness with which he took evolutionary time and its implications for all living beings, including Homo sapiens. This evolutionary insight was filtered through a close reading of Schopenhauer, the thinker Wells mentioned more regularly and consistently through the course of his career than any other thinker. It was this blend of Schopenhauerian pessimism and evolutionary theory which laid the foundations for the unique combination of poetic insight and raw intellect that distinguishes his work to this day. Decades before it became widespread, Wells was the first high-profile Cassandra figure, warning us of the unsustainable way we lived our lives.

As it did for most people of his generation, the onset of the First World War produced a new range of conflicts which Wells felt the need to explore. While being suspicious of patriotism, Wells deeply loved England, and his wartime books, both fiction and non-fiction, reflected this tension. The best of his wartime works were Mr Britling Sees it Through (1916) and The Undying Fire (1919). The war also brought on a short phase of quasi-mystical religiosity, which looked to articulate an idea of the immanent God. God the Invisible King (1917) anticipated later works like The Religion of Man (1931) by Rabindranath Tagore and Honest to God (1963) by Bishop Robinson. Wells soon tired of that approach and returned to what he called in his autobiography ‘the sturdy atheism of my youth.’

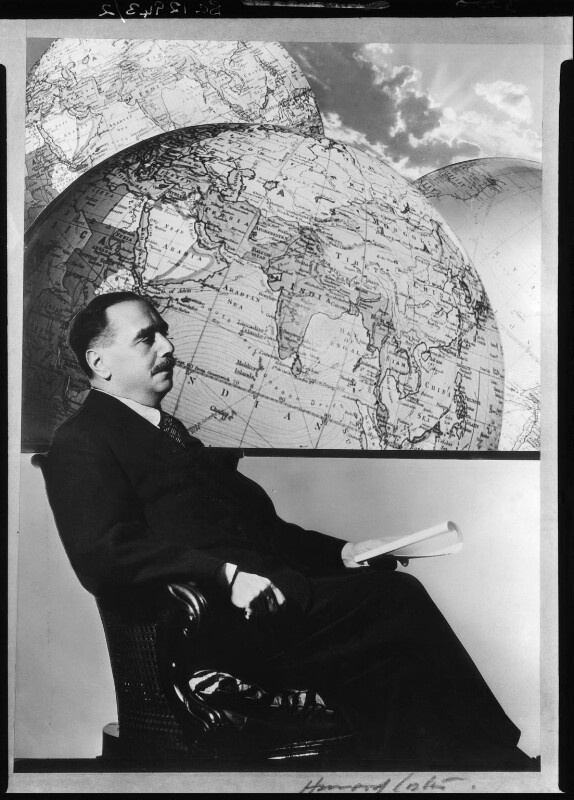

After the war, Wells embarked on a series of what have been called textbooks for the world. They were the Outline of History (1920), the best-selling historical work of the twentieth century, The Science of Life (1931) and The Work, Wealth, and Happiness of Mankind (1932). In each of these works Wells was concerned to place humanity in its natural setting and subject to the same evolutionary pressures of change and development as all other living things. He downplayed the role of great men in history and was suspicious of national histories, preferring to concentrate on our development as a species. The Science of Life steered readers away from the fashionable errors of the day, such as eugenics, and advocated a straight-forward Darwinism that has stood the test of time. Wells was among the very first to warn of the dangers to humanity of anthropogenic climate change. He was also a strong proponent of the conservation of natural resources half a century before this became part of the cultural mainstream. In 1928, Wells published The Open Conspiracy: Blue Prints for a World Revolution, envisioning ‘a world revolution aiming at universal peace, welfare and happy activity’. This was influential on fellow humanists such as Bertrand Russell, and on the formation of the Federation of Progressive Societies and Individuals (later the Progressive League) in 1932.

Largely in the service of this vision Wells produced a steady stream of novels. The most outstanding works from the interwar years were Christina Alberta’s Daughter (1925), a study of the dangers of succumbing to transcendental fantasies, Mr Blettsworthy on Rampole Island (1928) a black-humored dystopia about the breakdown of the Edwardian consensus about progress, and The Bulpington of Blup (1932), a comic look at human pretensions. Wells also became known in his capacity as a prophet of the modern age. He foresaw, for instance, trends such as the abolition of distance, aerial warfare, suburbia, committed relationships outside marriage, nuclear war, even the internet.

Wells continued to produce engaging work until the last year of his life, highlights being The Croquet Player (1936), an allegory with surprisingly contemporary resonance, World Brain (1938), his forecast of the internet, and You Can’t be Too Careful (1941), his last novel. During the Second World War, he was instrumental in composing a Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which exerted an influence on Eleanor Roosevelt’s work to formulate the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Wells’ last work, Mind at the End of Its Tether (1945), is often cited as evidence of his deep disillusionment with the scientific optimism he had spent his life advocating. This claim, however, is unjustified. The lifetime influence of Schopenhauer meant Wells was never the vapid optimist he was accused of being. Since his earliest scientific romances Wells had been ambivalent about the power of science and notions of easy, unlimited progress which were commonly said to be the by-product of science. Wells’ career was an ongoing reflection about humankind’s uncertain capacity to use responsibly the power that science was handing it. Wells died on 13 August 1946.

By Bill Cooke

Bill Cooke is a historian of humanism. His most recent book is H G Wells and the Twenty-first Century (Liverpool University Press, 2023). Other works include a biography of Joseph McCabe, the centenary history of the Rationalist Press Association, and an intellectual history of humanist thought since the Enlightenment.

Ludovic Kennedy was a writer, journalist, and broadcaster, known for his investigations into miscarriages of justice. A human rights campaigner, he […]

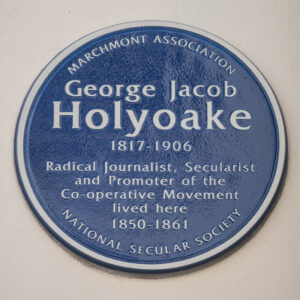

On Woburn Walk is a plaque to George Jacob Holyoake (1817-1906), a writer, lecturer, and promoter of the Cooperative movement, […]

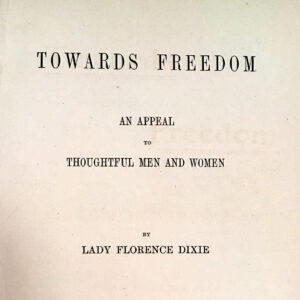

Truth needs the friendly grip of earnest men and women of every class. There is no distinction where it dwells. […]

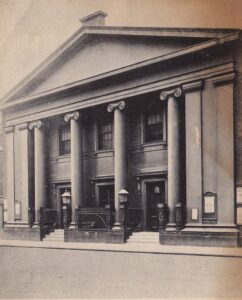

Under its successive names, adopted or given… is traceable a constant endeavour to study carefully, and keep abreast of, the […]