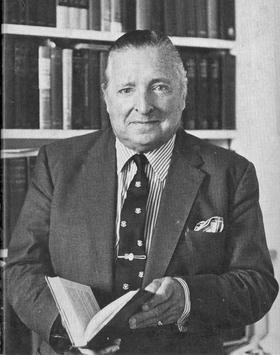

Harford Montgomery Hyde was a Belfast-born barrister, politician, author, and humanist, who championed humane legal reforms and progressive social attitudes. Rejecting religion as a young man, Hyde described himself as a humanist for the rest of his life. He was active in the Howard League for Penal Reform, in campaigns for the abolition of the death penalty, and in support of the decriminalisation of homosexuality – the latter seeing him deselected by his party.

The biography reprinted below was first published in October 2009 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography. It is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International license.

Hyde, Harford Montgomery

Contributed by Maume, Patrick

Hyde, Harford Montgomery (1907–89), barrister, politician, and author, was born 14 August 1907 in Belfast, son of James Johnstone Hyde JP, linen merchant, and his wife, Isobel (née Montgomery). Hyde claimed distant kinship with Henry James. His mother’s family had a strong liberal tradition and his maternal grandfather was a home-ruler. Hyde’s father was an Ulster unionist activist and Belfast councillor (1923–8). In 1914 UVF [Ulster Volunteer Force] guns were stored at the family home at Cultra (north Down) and UVF nurses practised bandaging on the young Harford. The family firm of Young & Hyde (founded 1897) provided a comfortable living during Hyde’s childhood, but failed in the late 1920s; Hyde recorded with mingled admiration and regret that his father paid his creditors in full. After the closure of his business James Hyde became the chairman of an electrical suppliers’ firm.

Hyde was initially educated at day schools in Bangor and Holywood, Co. Down. After boarding at Mourne Abbey School, Co. Down, in 1918 he won a scholarship to Sedbergh School in Yorkshire. His father wished him to enter the family business when he left school. Hyde took the matriculation examination for QUB, and won a scholarship, which he took up when it became clear that he was unsuited to business. While studying at QUB (1925–8) he had a catholic girlfriend with whom he attended mass; he was aesthetically attracted by the ritual and considered converting to catholicism but retreated in the face of his parents’ horrified reaction and his own developing sexual appetite. In 1926, while convalescing from diphtheria contracted on a visit to Spain, Hyde read Gibbon, the historian of Rome, and responded to his anti-Christian arguments. His disbelief in revealed religion was confirmed by The rise of rationalism (1865) by W. E. H. Lecky and Winwood Reade’s Martyrdom of man (1872); for the rest of his life Hyde considered himself a humanist. His aesthetic feelings were diverted to his lifelong hobbies, criminology and music.

Hyde read Gibbon, the historian of Rome, and responded to his anti-Christian arguments. His disbelief in revealed religion was confirmed by The rise of rationalism (1865) by W. E. H. Lecky and Winwood Reade’s Martyrdom of man (1872); for the rest of his life Hyde considered himself a humanist.

Hyde took a first-class honours BA in modern history in 1928 with a dissertation on Lord Castlereagh and the Act of Union. He was an open exhibitioner in history at Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1928–30, graduating with second-class honours in jurisprudence. He occupied the rooms at Magdalen that had belonged to Oscar Wilde, befriended Lord Alfred Douglas, and collected Wildeana. His parents feared (needlessly) that he might be homosexual: after sexual initiation on a visit to France in 1928 he became adept at smuggling women into his college rooms.

During his studies Hyde learned Russian, and he visited the Soviet Union in 1933; he subsequently described his unfavourable impressions to Conservative and Unionist associations. He was briefly Oxford University extension lecturer in history (1934), lecturing on Russia from Peter the Great to the Bolshevik revolution. He was a Harmsworth law scholar at the Middle Temple, 1932–4, and was called to the bar in 1934. In the same year he received a D.Litt. from QUB (he was awarded a second, honorary, D.Litt. in 1984). At this time he began his journalistic career, writing for the New Age as ‘Eric Montgomery’ (though he published his books under the name H. Montgomery Hyde). Lord Londonderry gave Hyde access to previously untapped family papers for his first major book, The rise of Castlereagh (1933). In 1934 Hyde became the Londonderrys’ librarian and in 1935 Londonderry’s private secretary and speech-writer; he filled this position until 1938, joining Lady Londonderry’s circle of friends, the Ark; the members were named after animals – Hyde was ‘Montgomery the Mole’, who dug up secrets. Hyde ghosted Londonderry’s account of his visits to Germany, as well as Lady Londonderry’s memoirs and her 1958 biography of the 3rd marchioness; he also collaborated with her in editing the correspondence of the eighteenth-century Wilmot sisters during their residence in Russia. Hyde was elected to the RIA in 1936.

In 1938 Hyde returned to the bar, building a practice on the north-eastern circuit… A 67-year-old client, who had spent half his life in prison, alerted Hyde to prison conditions; he joined the Howard League for Penal Reform, and served on its executive in the 1950s.

In 1938 Hyde returned to the bar, building a practice on the north-eastern circuit (assisted by Londonderry’s influence in Durham). A 67-year-old client, who had spent half his life in prison, alerted Hyde to prison conditions; he joined the Howard League for Penal Reform, and served on its executive in the 1950s. Hyde’s pre-war publications included Air defence and the civil population (1937, with G. R. Nuttall), used as a manual by the Irish government during the second world war. His interest in flying (encouraged by Londonderry) later brought him an RAF Museum Leverhulme fellowship, 1971–5. This allowed him to research and write British air policy between the wars (1976), which defends Londonderry’s ministerial record as air minister (1931–5).

In April 1939 Hyde married Dorothy Mabel Brayshaw (née Crofts). He joined the army officers’ emergency reserve in 1938, and in 1939 was recruited to MI6. Hyde was commissioned in the intelligence corps in 1940, and operated postal censorship in Britain, Gibraltar (1940), and Bermuda (1940–41). In 1941–4 he worked in New York for the counter-espionage and propaganda organisation British Security Coordination (headed by the Canadian businessman Sir William Stephenson); he circulated black propaganda in Latin America, sometimes involving forgery. Hyde was promoted major in 1942. In 1944 he returned to Europe, was attached to Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, 1944–5, and became legal adviser to the allied commission for Austria. Hyde oversaw the construction of the postwar Austrian legal system, insisting on the abolition of capital punishment. In December 1945 he retired from the army with the rank of lieutenant-colonel.

Hyde oversaw the construction of the postwar Austrian legal system, insisting on the abolition of capital punishment. In December 1945 he retired from the army with the rank of lieutenant-colonel.

After the war Hyde picked up his legal career. He was assistant editor of the official Law Reports, 1946–7, and legal adviser to Alexander Korda’s British Lion Film Corporation, 1947–9, drawing up actors’ contracts – he had met Korda during his wartime propaganda work. He also developed a reputation as a legal historian and biographer, editing The trials of Oscar Wilde (1948) and publishing Oscar Wilde: the aftermath (1963), biographies of Wilde (1975) and Lord Alfred Douglas (1984), and editions of Wilde’s works and texts associated with him. Trials inspired a film of the same name (1960), with Peter Finch as Wilde; and in 1982 BBC2 adapted the biography with Michael Gambon as Wilde. Hyde’s 1953 biography of the politician Edward Carson combined his interest in Wilde with his activities as legal historian and Ulster unionist.

He also developed a reputation as a legal historian and biographer, editing The trials of Oscar Wilde (1948) and publishing Oscar Wilde: the aftermath (1963), biographies of Wilde (1975) and Lord Alfred Douglas (1984), and editions of Wilde’s works and texts associated with him.

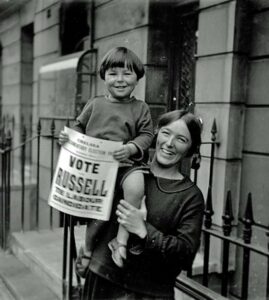

Hyde sought the unionist parliamentary nomination for Fermanagh and South Tyrone before the war. In 1945 he missed the South Belfast nomination by a single vote (despite the assistance of his father, chairman of the Cromac branch). He maintained contact with Ulster politics through the Queen’s University Club and the London Ulster Club (which he co-founded); he regularly spoke on the need for unionists to counter Free State propaganda. To promote his political ambitions he had been initiated as a freemason into Ulster Masonic Lodge no. 2972 in October 1944; in April 1949 he joined Eldon Loyal Orange Lodge no.7, excusing his hypocrisy with the thought ‘Paris was worth a Mass’ (PRONI, MS autobiography). In 1949–50 Hyde cultivated the North Belfast constituency, which led to his nomination and victory in the 1950 general election. Constituency activists were initially unaware that he had speculated in print on the sexuality of William III. Hyde never sought higher office; he saw himself as a ‘literary Member’ (PRONI. M. autobiography), supplementing his income with a political column for the Irish edition of Empire News. Nationalists called him a typical unionist absentee MP, more interested in Oscar Wilde than North Belfast; unionist contemporaries claimed that his stormy career reflected arrogance and ‘political stupidity’.

Hyde’s absences from London led to the breakup of his first marriage. Both Hydes had engaged in wartime infidelities and Dorothy now fell in love with another man. The marriage was dissolved in 1952, to Hyde’s regret. He stipulated that Dorothy should campaign for him in the 1951 election, that he should be the petitioner, and that the proceedings should be as discreet as possible; his constituency workers were unaware of the divorce until Hyde married Mary Eleanor Fischer in 1955. This marriage was unsuccessful; Hyde complained that Mary cared only for horses and hunting. (He remained on good terms with Dorothy until her death in 1979; she guaranteed his overdraft in the early 1960s.)

Hyde continued to concern himself with a great variety of causes and enterprises. He served on the UK delegation to the assembly of the Council of Europe in 1952–5. In May 1954 he attended the founding meeting of the Bilderberg group.

Hyde continued to concern himself with a great variety of causes and enterprises. He served on the UK delegation to the assembly of the Council of Europe in 1952–5. In May 1954 he attended the founding meeting of the Bilderberg group. In the same year he wrote an introduction to The Irish and catholic power by Paul Blanshard. He advocated the return of the Hugh Lane collection of paintings from London to Dublin; when Belfast constituents protested, he retorted that Carson took the same view. In 1956 he ensured that the UK copyright deposit status of Trinity College Dublin Library was safeguarded.

From the mid-1950s Hyde was involved in a series of actions that reflected his views on homosexuality and capital punishment. In 1956 he raised the issue of the Casement diaries in parliament, which led to their being made available for public scrutiny from 1959; he became the first scholar to examine them. Suggestions that Hyde was part of an official conspiracy to authenticate the diaries are unfounded: he was acting purely on principle. He edited The trial of Roger Casement for the Notable British Trials series in 1960 and dramatised it for BBC radio in 1961. The book was banned in the republic. Hyde also secured the release in 1960 of Wilde’s prison records. In 1956 Hyde seconded Sidney Silverman’s motion for the abolition of capital punishment, annoying constituents concerned by the IRA border campaign. He helped to secure the formation of the Wolfenden Committee; his outspoken parliamentary support for its report on the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1958 triggered deselection attempts, the success of which was virtually assured by his insouciance.

In 1956 Hyde seconded Sidney Silverman’s motion for the abolition of capital punishment… He helped to secure the formation of the Wolfenden Committee; his outspoken parliamentary support for its report on the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1958 triggered deselection attempts, the success of which was virtually assured by his insouciance.

Hyde’s unionism reflected his background and dislike of postwar Labour party authoritarianism; now he was bored with Belfast politics, preferring the new social liberalism of the Labour party. He retired at the 1959 election, promptly leaving the Orange and masonic orders. His parliamentary service fell two months short of a pension and after his retirement his extravagant lifestyle produced severe financial problems, only partly assuaged by the rewards of prolific journalism. However, his interest in Irish affairs was not at an end: in 1968 Hyde supported an inquiry into the batoning of civil rights marchers, and he later advocated a federal state of thirty-two counties with its capital in Armagh.

In 1959 Hyde became professor of history and political science at the University of Punjab, Lahore, where he remained until 1961, taking time off in 1960 to cover the Moscow trial of the American spy pilot Gary Powers for the Sunday Times. Hyde resigned his chair to write a commissioned biography of Sir William Stephenson. The quiet Canadian (1962; entitled Room 3603 in the United States) drew extensively on a report of 1943 by Hyde. The book created a minor sensation; there were calls for Hyde to be prosecuted (he had named the wartime head of MI6). The book was marred by Stephenson’s exaggerations and Hyde’s carelessness (faults magnified in a later volume of Stephenson’s memoirs which used a different ghostwriter), which involved Hyde in two expensive libel settlements. Hyde later wrote another biography on a figure associated with British Security Coordination, Cynthia (1965), about the agent Elizabeth Thorpe; he privately admitted that her claims were largely fictional, but he published them to please her because they had been lovers.

From 1962 Hyde ceased to practise as a barrister and became a professional writer, publishing a book a year… He published a History of pornography in 1964, and in the 1960s he was an expert witness in several obscenity trials… In 1970 Hyde published a history of British homosexuality, The other love.

From 1962 Hyde ceased to practise as a barrister and became a professional writer, publishing a book a year. He sold his Wildeana for $30,000 to an American collector. His book collecting bore witness to an interest in erotica. He published a History of pornography in 1964, and in the 1960s he was an expert witness in several obscenity trials. (His last publication, issued posthumously, was an account of the Lady Chatterley’s lover trial.) In 1970 Hyde published a history of British homosexuality, The other love.

Hyde’s second marriage was expensively dissolved in 1966, in which year he married Rosalind Roberts (formerly Dimond), his secretary since his employment with Korda. She typed his works and advised him on legal matters. They lived for a while at Lamb House, formerly Henry James’s home, at Rye, Sussex; Hyde called Henry James at home (1969) his favourite among his own works because of James’s awareness of the evil wrought by the tyranny of one person over another. In his later years the Hydes lived at Tenterden, Kent. Many of Hyde’s later works were commissioned biographies or works of popular history and criminology; he sold research material to antiquarian dealers once he had exhausted a subject. He produced a total of about fifty books, despite declining health in his later years (he suffered two strokes in 1976 and a heart attack in 1987). He died in hospital in Ashford, Kent on 10 August 1989.

He prefigured later attempts to develop secular and socially liberal forms of Ulster unionism, but also aspired to an older archetype – the raffish clubman, despising suburban moralism and delighting in the arcane worlds of the aristocrat, the pornographer, the barrister, the prostitute, and the spy.

Hyde’s significant achievements as a popular historian were undermined in his later work by a fondness for striking anecdotes; his 1971 biography of Stalin used dubious sources to argue that the dictator had once worked for the Tsarist secret police, and he gave credence to an alleged recording of Wilde’s voice, which has since been exposed as a forgery. He prefigured later attempts to develop secular and socially liberal forms of Ulster unionism, but also aspired to an older archetype – the raffish clubman, despising suburban moralism and delighting in the arcane worlds of the aristocrat, the pornographer, the barrister, the prostitute, and the spy.

Some of Hyde’s papers are held at Churchill College, Cambridge; the Humanities Research Centre of the University of Texas at Austin (including much material relating to Casement, Wilde, and Henry James); and the PRONI, which holds an unpublished manuscript autobiography of his life up to 1952.

H. Montgomery Hyde (ed.), Trial of Sir Roger Casement (1960); H. Montgomery Hyde, The quiet Canadian (1962); Belfast Telegraph, 17 Mar. 1966, 13 Jun. 1969, 18 Jan. 1977; Ronald Lewin, Ultra goes to war (1978; rev. ed. 1988); H. Montgomery Hyde, Secret intelligence agent (1982); H. Montgomery Hyde, Lord Alfred Douglas (1984); Ir. Times, 5 Jan. 1985; Belfast Newsletter, 12 Aug. 1989; Ir. Times, 14 Aug. 1989; The Times, 12 Aug., 17 Aug. 1989; WWW; Timothy J. Naftali, ‘Intrepid’s last deception: documenting the career of Sir William Stephenson’, Intelligence and National Security, viii, no. 3 (July 1993); Angus Mitchell (ed.), The Amazon journal of Roger Casement (1997); British Security Coordination: the secret history of British intelligence in the Americas, 1940–45, intro. by Nigel West (1998); Stephen Dorrill, MI6: fifty years of special operation (2000); Nigel West, Counterfeit spies (1998); Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: the battle for the code (2000); Jeffrey Dudgeon, Roger Casement: the black diaries (2002)

I see this kind of love – the empathy that should be common to all living creatures – rather than […]

I believe in the equality of man; and I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy and […]

Universal rights are exactly that, universal, and one should not suddenly acquire different rights after a certain number of birthdays. […]

…that perfect Tranquility of Life, which is no where to be found, but in retreat, a faithful Friend and a […]