Humanism is less concerned with what to believe than with how to live. The meaning it gives to life lies in the effort to remove the obvious causes of suffering and frustration and extend the range of human sympathies. Today it is not the individual soul but the world itself that must be saved.

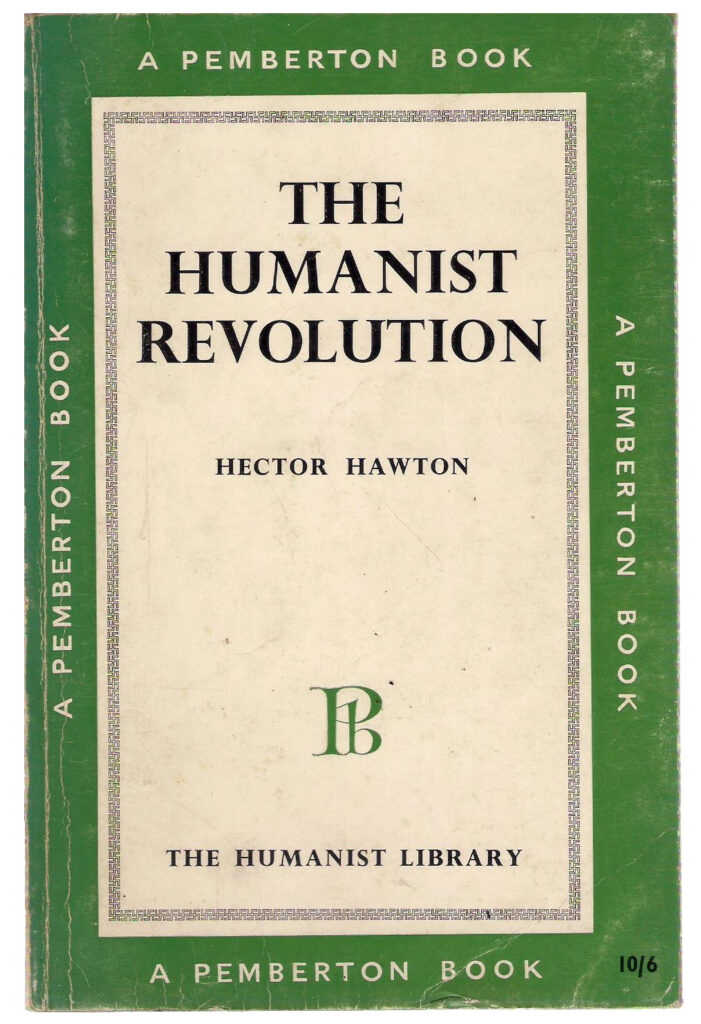

Hector Hawton, The Humanist Revolution (1963)

Hector Hawton was a novelist, editor, and influential humanist, whose 1963 book The Humanist Revolution helped give vivid expression to the movement. In cooperation with H.J. Blackham, Hawton was instrumental in increasing cooperation between humanist bodies during the 1950s, and forming the umbrella British Humanist Association of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK) and Rationalist Press Association (RPA). Hawton was also actively involved in the formation of the International Humanist and Ethical Union (now Humanists International), drafting the text of its statement of values, The Amsterdam Declaration. Under his editorship, the Literary Guide became The Humanist in 1956, helping to usher in a conscious identification with the values – intellectual and lived – of humanism.

On the next integrative level man will have to learn to live without gods. Scientific knowledge will take the place of superstition, and poetry will take the place of magic.

Hector Hawton, Men without Gods (1948)

Hector Hawton was born in Plymouth on 7 February 1901, the son of a railway engineer. He was educated at Plymouth College, before embarking on a career in journalism which spanned half a century. Hawton wrote first for the regional Western Morning News, and later in London, before moving to Hampshire to work as a freelance writer. As well as journalism, Hawton published romances, thrillers, and children’s books: at least one a year for almost three decades.

Hawton was raised as a Calvinist, converting to Catholicism during his teens, before leaving behind religion altogether in favour of science and rationalism. But, as H.J. Blackham would later write, he ‘was no dry rationalist.’ His interests straddled the worlds of reason and art: ‘A disillusioned romantic, without bitterness, he needed poetry in place of those lost illusions’. His first publication for the Rationalist Press Association was a 1940 pamphlet entitled Why Be Moral?, which argued for a humane rationalism even in the midst of war – during which he served in the Royal Air Force.

Between 1945-1950, Hawton edited the Thinker’s Digest, an RPA quarterly presenting extracts of its current literature. In 1948, he became Secretary of the South Place Ethical Society, where he remained for six years. In 1952, he accompanied H.J. Blackham to the Netherlands, where he drafted the final version of what became known as the Amsterdam Declaration: an expression of international humanist values. This, as Blackham later recalled, required careful appeal to those members of the burgeoning International Humanist and Ethical Union who remained rooted in the ‘Ethical’ movement: creating ‘documents to which the American Ethical Union leaders could subscribe as well as the Humanists among us.’

Shortly after the successful formation of this unified international humanist body (today Humanists International), Hawton began his long editorship of what was then still the Literary Guide, becoming managing editor of all RPA books and periodicals on the death of Frederick Watts in 1953. In 1956, he became managing director, and played a leading role in expanding the scope and securing the future of the organisation. That year, the Literary Guide was renamed The Humanist. As Christopher Macy, his editorial successor, would write after Hawton’s death:

… he transformed the Literary Guide from the spearhead of an advance attack into the embodiment of a whole army of rationalistic, freethinking Humanism; he changed the title to the Humanist as he played his part in creating the humanist movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

This was a task he undertook, wrote Blackham, ‘widely informed, with the caution of commonsense, alert to what was going on in the world around, and with strong and hard-won convictions’.

In addition to his administrative and organisational roles, Hawton wrote a series of books giving expression to the values of humanism, and lending weight and appeal to its philosophical tradition. These included Philosophy for Pleasure (1949), The Thinker’s Handbook (1950), The Feast of Unreason (1952), and The Humanist Revolution (1963). He also edited Reason in Action (1956), containing contributions from Archibald Robertson, J.B. Coates, Donald Ford, and H.J. Blackham.

Hawton retired from the Rationalist Press Association in 1971, but remained active as a director of both the RPA and the IHEU. In 1974, he became an Appointed Lecturer at South Place, and in the same year briefly returned to (by then) the New Humanist as acting editor. In 1975, Hawton became ill with cancer, and died on 14 December that year. His death was a shock to friends and colleagues local and international. As H.J. Blackham wrote:

We were all shocked when a gust blew out the light.

In the age-long battle against superstition, Hector Hawton was the happiest of warriors.

Margaret Knight

Letters to the New Humanist after Hawton’s death recalled him as a humane and good natured man, adept at ‘puncturing pomposity’, and sublimely skilled in crystallising complex ideas into simple expression, without losing their depth or clarity. A shining example of this latter was Philosophy for Pleasure, a comprehensive, accessible account of the history of Western philosophy. His tireless work for The Humanist was also noted, not least in turning to the use of half a dozen pseudonyms to conceal those occasions when huge swathes of an issue would be the work of Hawton alone.

Editor of The Freethinker, Bill McIlroy, noted that ‘Hector’s enthusiasm for the battle against religion was combined with compassion and sympathy for its victims.’ Director and author Roger Manvell described him as ‘a very integrated human being who put ‘people first’ and the stiffer matters of doctrine second.’ Adding that ‘his Humanism sprang directly from his concern for humanity’. Dutch humanist Nettie Klein, a year after Hawton’s death, noted the gap created by his absence from the IHEU board meeting:

One man we all sadly missed this time was Hector Hawton. In commemorating him, Harold Blackham spoke of his extraordinary skill in expressing complicated ideas in a clear, simple language, and reminded us that Hawton drew up the Declaration of what IHEU stands for at the Amsterdam Congress in 1952. Howard Radest, one of the three Co-Chairmen of IHEU, talked of Hawton’s pleasant personality and his wit which used to brighten some of our drearier sessions. I cherish memories of sneaking off with Hector to a bar when we ran out of patience with the rhetoric of certain speakers at congresses.

The closing paragraph of Hawton’s obituary in the New Humanist, outlined his threefold legacy:

… historically, as the most prominent representative of and the most prolific writer in the rationalist section of the Humanist movement during one of its most critical periods; intellectually, as the author of several works of rationalist theory which stood out for their clarity and cogency; and personally, as an encouraging and entertaining friend of Humanists and many other people all over the world.

I have no view but public good; certainly no desire to injure any one, but a passionate desire to do […]

Atheism, unadulterated and undisguised, was diffused into every corner of the land, and the bold voice of the conscientious unbeliever […]

Thomas Hill Green was a philosopher, educator, and a Liberal, whose idealist philosophy (with its practical implications) was a significant […]

Wales has long been a nation of nonconformists, with a history of challenging the power and influence of the established […]