Life would be far more truly envisaged if we dropped the silly phrases “men’s and women’s questions”; for indeed there are no such matters, and all human questions affect all humanity.

Helena Swanwick, Women and War (1915)

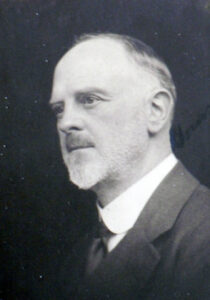

Helena Swanwick was a suffragist and peace campaigner who vigorously opposed what she saw as the stupidity and inhumanity of war. She attended two League of Nations assemblies as a member of the British delegation and was appointed a Companion of Honour in recognition of her work for peace and the enfranchisement of women. Swanwick used the word ‘humanist’ to mean the unifying of all humanity in efforts to improve and reform, but in her early rejection of religion and devotion to principles derived from her own reason and compassion, she sits comfortably alongside those other humanists who put peace and international cooperation at the heart of their life and work.

I regarded peace not as a state you could work for in the abstract, but as the condition which would result from a just and fair conduct of national and international relations.

Helena Swanwick, I Have Been Young (1935)

Helena Maria Lucy Swanwick was born in Munich, the daughter of Oswald Sickert, an artist of Danish birth who brought his family to Britain in 1868. Settled in London, her father moved in artistic circles and as a child Swanwick met Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris, George Bernard Shaw, Leslie Stephen, and Oscar Wilde, whose compassion, laughter and sense of fun she never forgot. Swanwick was educated at the Notting Hill High School for girls and at Girton College, Cambridge where she studied psychology, economics and logic. After graduation she taught psychology at Westfield College, London before moving to Manchester where she wrote for the Manchester Guardian and undertook voluntary social work among working-class women.

As the only girl in a family of six children, Swanwick was expected to help look after her brothers and resented the fact that they were allowed to go out alone while she was not. Her reading of Shelley, and of John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women, revealed the ‘marvellous fact’ that they were both feminists and that she too was a feminist. Swanwick had already rejected her mother’s religious beliefs due to the influence of a freethinking teacher, and she became a socialist when she discovered that Labour was the only party willing to support women’s rights.

In 1906 Swanwick joined the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, becoming in 1909 the founding editor of the NUWSS paper which she called The Common Cause to reflect her belief that women and men should work together to get women the vote. However, she resigned the editorship in 1912 because the NUWSS executive committee would not let her criticise the increasing violence of the suffragettes. A convinced pacifist, Swanwick resigned from the NUWSS altogether in 1915 when the organisation decided to support Britain’s war effort. She then became Chair of the British section of the newly-formed Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and was largely responsible for the League’s strong opposition to the post-war blockade of Germany and the punitive terms of the Versailles Treaty.

During the First World War, Swanwick courageously argued that the conflict should be ended through negotiation. At the same time, her hope that future wars might be prevented led her to become active in the Union of Democratic Control which was campaigning for parliamentary oversight of British foreign policy. In 1924 she took over the editorship of the UDC paper Foreign Affairs, and subsequently attended the fifth and tenth assemblies of the League of Nations in Geneva as a member of the British delegation. She became Vice President of the League of Nations Union and addressed many public meetings on its behalf.

In 1931 Swanwick left public life and retired to Maidenhead: ‘I have had my say; now I cultivate my garden’. On 16 November 1939, depressed by the death of her husband, her own poor health, and the outbreak of the Second World War, she took her own life at her home.

The earlier struggles of women for emancipation necessarily take the form of beating at the closed doors of life. Till these are opened and we can see for ourselves what there is of knowledge and opportunity we cannot know how much we can put to good use. Many of these doors are still closed, but far more have been opened even in my lifetime than, as a girl, I should have ventured to hope.

Helena Swanwick, Time and Tide, 4 November 1927

During her lifetime, Swanwick’s criticisms of organised religion did not go unnoticed by fellow freethinkers. In 1935, following the publication of I Have Been Young, The Literary Guide (now the New Humanist) – under the heading ‘A Feminist on the Church’ – quoted Swanwick’s belief that ‘most of the Churches have become protectors of wealth and vested interests; they have defended slavery and recruited for war, and have been among the most persistent opponents of the emancipation of women’. Like other humanist activists of her generation, Swanwick was unafraid to level such criticisms, and followed her own sense of right and wrong in championing the causes she believed in.

Helena Swanwick, I Have Been Young (1935)

Helena Swanwick | Spartacus Educational

By Paul Ewans

Stanton Coit was a pioneer of the Ethical movement in England and the founder of the West London Ethical Society, […]

Is it not the duty of every person to promote the happiness of others as much as lies in their […]

To all those who have established and who are maintaining the right to refuse to kill. Their foresight and courage […]

Eliza Flower was a composer, a radical, and a significant influence on William Johnson Fox and the progressive values of […]