The Humanist Broadcasting Council was established in 1959, in consultation with the BBC, to advocate for the inclusion of humanist viewpoints in television and radio. Its members included A.J. Ayer, Harold Blackham, Cyril Bibby, Lord Chorley, Jacob Bronowski, E.M. Forster, Morris Ginsberg, Sir Julian Huxley, Margaret Knight, Bertrand Russell, and Lord Francis-Williams, and for a number of years the Council advised on programming from a non-religious standpoint.

Four years before the Humanist Broadcasting Council was formed, Margaret Knight’s talks on morality without religion for the BBC Home Service had been met with a mix of outrage and admiration. As Callum Brown has since argued, the reaction ‘exposed the apparent vigour of Christian culture in Britain, including within the BBC,’ but so too did it demonstrate a divide in public opinion, with many (including the religious) expressing support for the humanist viewpoint.

The Beveridge Broadcasting Committee of 1949 had recommended that bodies which studied moral or spiritual issues, including the non-religious, should have the opportunity to broadcast, but only via the Talks Department rather than the Religious Broadcasting Department. In 1958 the Humanist Association complained that this recommendation was not being implemented. The following year, a group of 24 leading figures came together to lobby the BBC on behalf of humanists and atheists. From then until the mid-1960s, the Humanist Broadcasting Council liaised with the BBC, the Independent Television Authority (ITA), and the School Broadcasting Council, to represent humanist interests, including by producing programme proposals.

In March 1960, Julian Huxley’s The Faith of a Humanist was broadcast on BBC Women’s Hour. Later that year, a suggestion by the committee that a re-enactment of the famous Huxley-Wilberforce debate be broadcast was approved. Humanists Julian Huxley and James Fisher provided comment on The Battle of Oxford, remembering a powerful debate over the merits of evolutionary theory between biologist and bishop. Such programmes did not escape the attention of some among the evangelically religious. In July 1960, The Humanist reported the words of Dr. J. Trevor Davis at the assembly of the Congregational Union, whose criticism was heaped upon these:

Intellectual stars of the radio and television, who with an air of insufferable arrogance derived from their supposedly superior knowledge of how it all began and how it will all end, instruct us foolish and misguided people that they have no need of God and religion is mere fantasy. The end of our race may well be dust if these intellectual thieves, these moral bandits, these spiritual robbers have their way.

In fact, the Humanist Broadcasting Council merely sought representation on an equal footing with the Christian viewpoint, and opportunities to engage in dialogue with regards to moral and ethical issues. A memorandum of 1961 urged that:

In 1962, the Pilkington Report examined the role of the BBC in wider society, and made recommendations for its future. The report stated that ‘by its nature, broadcasting must be in a constant and sensitive relationship with the moral condition of society,’ and – though working from the premise that England was a ‘Christian country’ – recommended that non-religious bodies be allowed their ‘fair share of time in controversial broadcasting outside periods set aside for religious broadcasting’. In 1967, a Broadcasting Committee was established by the British Humanist Association ‘to do the spade-work of lobbying and putting up ideas for programmes… to ensure continuing and expanding work in a difficult field’.

Although the Humanist Broadcasting Council had some measure of success prior to their dissolution in the 1960s, the representation of non-religious viewpoints in television and radio remained overwhelmingly unsatisfactory. Nicolas Walter, writing in the New Humanist in 1976, wrote that:

the first principle we [humanists] have in common is a commitment to freedom of speech; so our objections to religious broadcasting amount to a demand not for the suppression of religious opinion but for the freer expression of all religious and also non-religious and anti-religious opinions on equal terms.

Walter went on to say that ‘ever since 1928, when the BBC was first allowed to broadcast on “matters of political, industrial and religious controversy”, we have been urging it to treat religion on the same basis as other controversial issues.’ He stated the situation of the 1960s and 1970s as one in which:

three per cent of all broadcasting is religious, and almost all of it is objectionable. Unorthodox Christianity, non-Christian religion, non-religious Humanism, and anti-religious secularism are allowed on the air only as reluctant concessions, and generally in Christian contexts… A degree of control, and even censorship, which would be unacceptable in moral, social, political, or cultural affairs, is still openly enforced in religious affairs.

Today, Humanists UK continues to advocate for the inclusion of humanist viewpoints in broadcasting, without which a significant body of thought – and portion of the UK population – remains underrepresented.

…for Shakespeare, in the matter of religion, the choice lay between Christianity and nothing. He chose nothing; he chose to […]

A cheerful and reverent Agnostic, whose whole life was one of unselfishness and devotion to lofty aims, who was tolerant […]

I felt flattered by the remark of a hostile journalist that I was “a compendium of the cranks,” by which […]

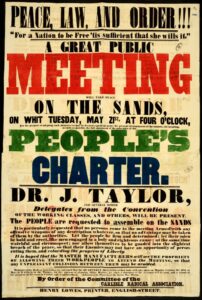

A mass working class movement for universal male suffrage Read more Chartist Ancestors and Women Chartists Chartism by David Avery […]