The Humanist Housing Association began in January 1955, founded as the Ethical Union Housing Association to provide affordable homes for the elderly and those in need. At the time, many housing associations were operated by religious groups, and excluded the non-religious. The Ethical Union Housing Association did not discriminate on grounds of belief or non-belief, but met an important need for those in the latter group, as well as enabling many humanists to give practical expression to their central values.

The first official meeting to establish the Association took place on 14 January 1955, supported by a £75 start-up donation from the Ethical Union and brought about by a small group seeking to put their humanist beliefs to work for positive change. Its central figures were Mora and Lindsay Burnet, Rose Bush, and Olga Blackham. The first public meeting took place in April at Conway Hall, with its 90 attendees demonstrating enthusiastic support for the initiative. The Ethical Union Housing Association aimed:

To provide high quality, value for money, affordable services to meet the housing, care and support needs of older people, people with learning disabilities and other special needs.

Donations were given by Hampstead Ethical Society, Conway Hall, the South Place Ethical Society, the Rationalist Press Association, and the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK). A grant of £3000 was given by the National Corporation for the Care of Old People. The Ethical Union Housing Association’s first project was a four-storey Victorian house in Hampstead: to be transformed into 14 bedsit flats, with cooking facilities and shared bathrooms. A humanist belief in autonomy, dignity, and sociability guided the development of this, and all subsequent projects, seeking to provide housing of a high standard, as well as ongoing support for residents. Burnet House welcomed its first tenants on 14 March 1957.

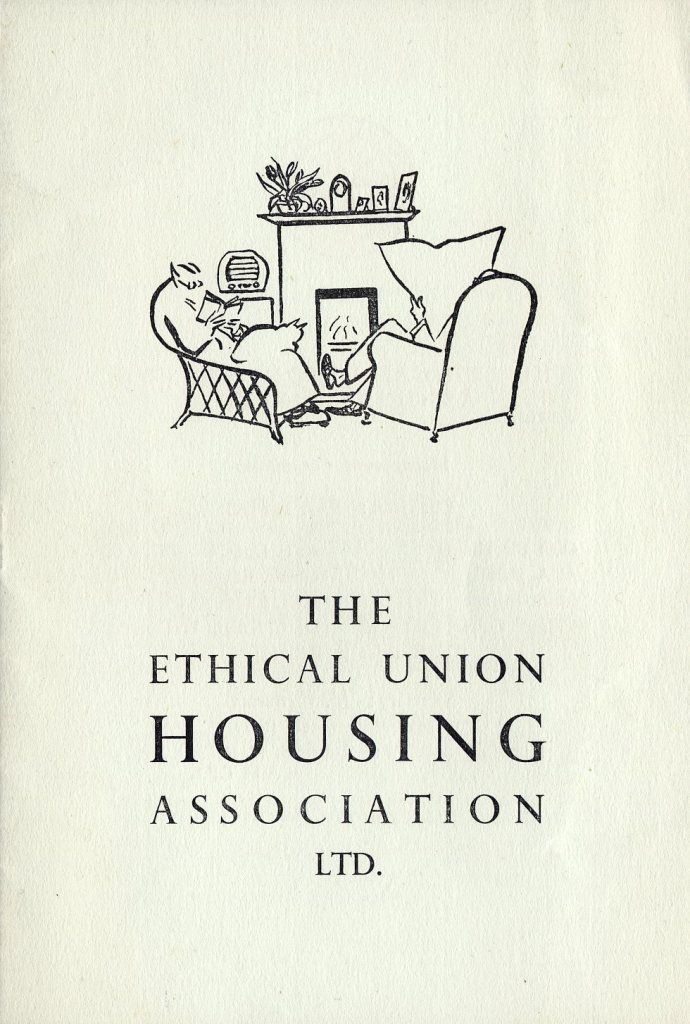

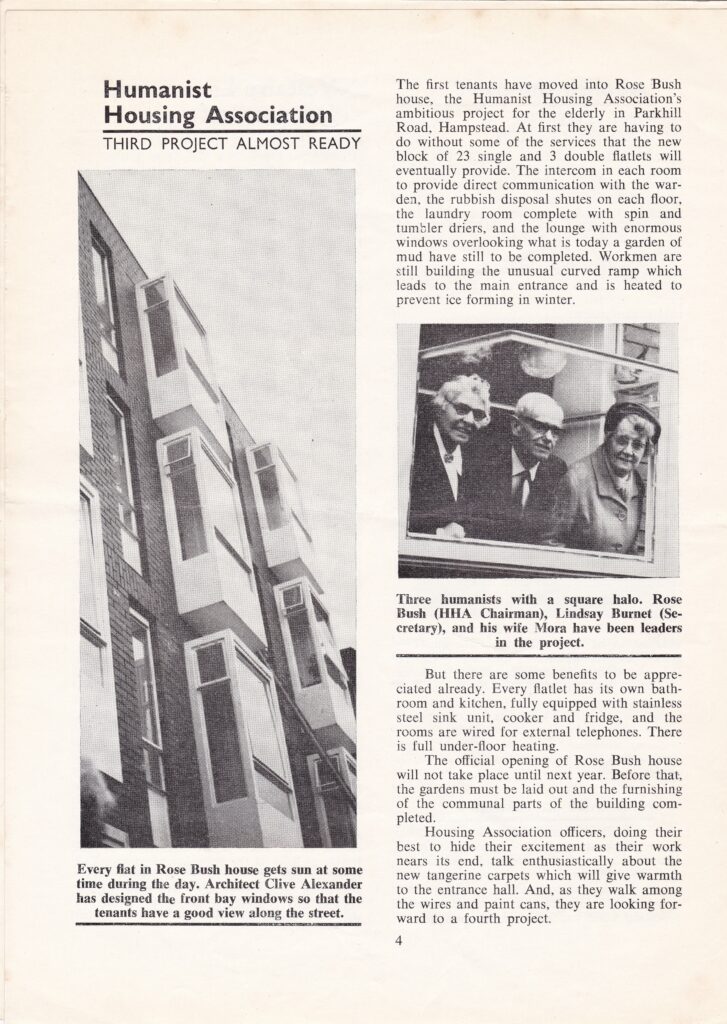

The Association received strong support and great interest, as well as many inquiries about availability. The second property was opened in 1963, named Blackham House (after Olga Blackham, a vibrant member of the management committee, and H.J. Blackham, a leading light of the humanist movement). Blackham House was a two-storey block of 20 self-contained flats, built on Worple Road, Wimbledon. Two years later, the Ethical Union Housing Association became the Humanist Housing Association, and in 1968 a third project – Rose Bush Court – was opened in Hampstead.

Over the following decade, the Humanist Housing Association continued to grow, developing sites outside of London (including Tunbridge Wells, Chelmsford, and Cambridge), and ultimately owning and managing 18 properties. Emphasis was placed on embodying humanist values, and enriching human lives: supporting the independence of tenants while providing opportunities for communal gatherings and social events. By the end of the 1970s, the Humanist Housing Association managed approximately 1000 flats. Members of the management committee kept in close contact with those living at the properties, and reports spoke of ‘warmth and friendship and humour among the tenants and staff’. Special mention was made of Mora Burnet, who was personable with tenants and effective as a member of management. Some tenants themselves became part of the management committee, and took an active part in the organisation of social events.

In 1980, the Humanist Housing Association celebrated its 25th anniversary, taking pride in the tremendous strides they had made since starting out two and a half decades earlier. As the years passed, and regulations increased and tightened, the Association was ever professionalised, including with the addition of new staff. By its 40th birthday, the Humanist Housing Association employed 129, and reported an annual turnover of £3.4 million. The Association also provided expertise and management support to other sheltered housing provision, enabling decades of experience to be shared, and revenue to be generated.

The 1990s saw a new reality for housing associations, and the Humanist Housing Association in particular. There had been a vast increase in secular housing provision, as well as rising maintenance costs, and limited financial assistance for housing associations. Towards the end of the decade, the HHA entered into discussions with the St Pancras Housing Association, recognising the need to discuss future options, but devoted to maintaining their distinctive identity and ethos. In 2000, the two associations agreed to merge, becoming the St Pancras and Humanist Housing Association. In 2004, it became Origin Housing, which continues to provide affordable housing and support services.

Looking back on the work of the Humanist Housing Association for the Ethical Record in 2000, former Chair Peter Heales wrote:

The association came into being at a specific time when humanists felt a specific need. One group of people who needed and deserved better housing were being excluded because they did not have a suitable religious affiliation. The ideals and dedication of its founders helped it pioneer modern standards, and the Association has always been a credit to its founding movement in the way it served its tenants.

Like many other contemporary initiatives, including the Agnostics Adoption Society, Humanist Counselling, and prison visits for the non-religious, the Humanist Housing Association emerged in recognition of the dominance of religious groups in the provision of vital services, and the consequent exclusion of humanists and the non-religious. Led by humanist values, and underpinned by a genuine desire to improve the lives of others, each of these gave practical expression to the humanist philosophy, placing compassion, companionship, and quality of life at their heart.

Conway Hall has effected a transformation. From the day of its opening the life of the Society has been full […]

People have always looked for ways to mark significant events in their lives, and though many ceremonies have often been […]

What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult for each other? George Eliot, Middlemarch […]

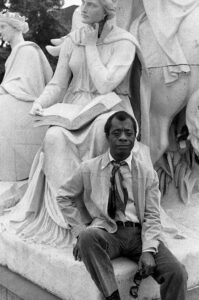

If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, […]