If the church was wrong, as of old, to trust to prayer in an epidemic, why shall she be right to trust pregnancy to divine guidance now? She accepts, now, the scientist’s way out of fever, and in a few years she will have accepted his way out of sex troubles. In the meantime people have to suffer for her backwardness in letting go the fantasy and adopting the reality.

Janet Chance, The Cost of English Morals (1931)

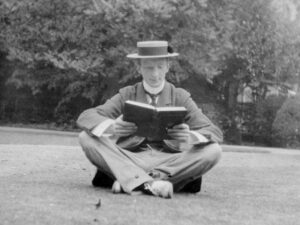

Janet Chance was a humanist, freethinker, and feminist who campaigned for sex education, birth control, and access to abortion. As Chair of the Abortion Law Reform Association, she led her colleagues in a campaign which led ultimately to the passage of the Abortion Act 1967.

Janet Chance was born in Edinburgh, the daughter of Alexander Whyte, who rose from a humble background to become Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland, and the feminist and pacifist Jane Elizabeth Barbour. In 1912 Chance married the businessman Clinton Chance who, like Chance herself, was reacting strongly against an intensely religious upbringing. The couple moved to London and became enthusiastic members of the Malthusian League, which advocated family planning and the dissemination of contraceptive information.

In 1924 humanists Dora Russell, Dorothy Thurtle and others founded the Workers’ Birth Control Group to give working women access to birth control information. Chance became aware through her membership of the Group that many working class women could neither access information about contraception nor afford birth control. She thus volunteered as a lay worker at the Wandsworth Birth Control Centre, and in 1929 she opened her own Sex Education Centre, providing sex education and instruction in sexual satisfaction for women. In the course of her counselling work Chance discovered to her horror that 16 out of a sample of 21 clients had attempted an amateur termination of pregnancy and this revelation caused her to focus increasingly on abortion rights.

Enforced motherhood, and its worse alternative, self-inflicted abortion, the shoddy preparation for marriage given to the young, the social maiming of unusual sexual types, the preservation of dead marriages – these things cannot be defended.

Janet Chance, The Cost of English Morals (1931)

Chance considered that the prevailing sexual morality of her time was destructive of human happiness, heavily influenced as it was by Christian doctrine. In her book The Cost of English Morals (1931) she insisted that sex was life-enhancing and that it should be enjoyed for its own sake, free of the restrictions imposed by religion. To that end, she argued in favour of sex education both to disseminate knowledge of contraception and to enable women to have satisfying sex lives. She rejected the view that extra-marital sex was wrong, and suggested that divorce should be available where a marriage had been destroyed by insanity, life imprisonment, alcoholism, cruelty or desertion. And she demanded that all medically advisable abortion should be legalised. To most of her contemporaries these were shocking, even scandalous ideas. Chance also published Intellectual Crime (1933) in which she insisted on the importance of a rigorous respect for the truth, and The Romance of Reality (1934) in which she promoted ‘realism’ as a way of life opposed to religion and supernaturalism.

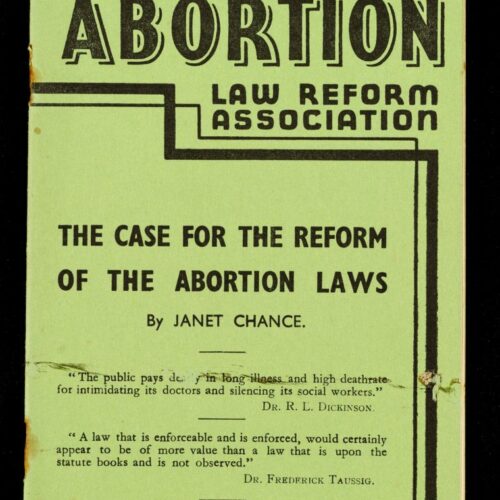

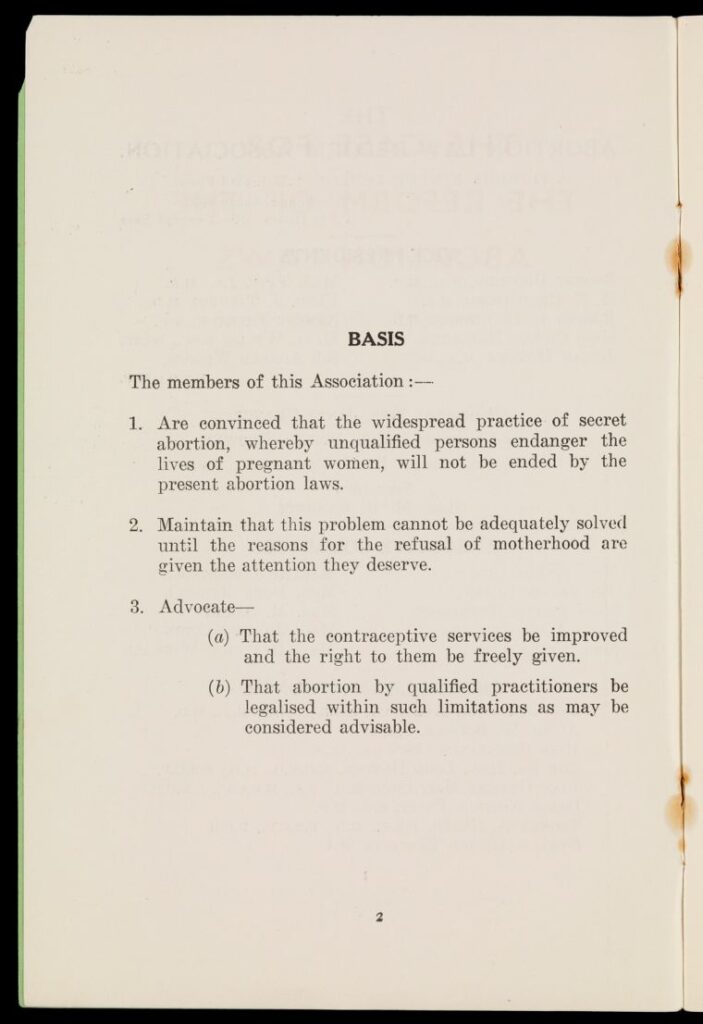

In February 1936 Chance and her fellow humanists Stella Browne, Alice Jenkins, Frida Laski, and Dora Russell met at Clinton Chance’s Piccadilly office and agreed to found a society for the reform of the abortion laws. The launch of the Abortion Law Reform Association took place at Conway Hall in May that year with Chance giving a speech from the Chair outlining ALRA’s policy. Membership of ALRA in its first year was just 35, but by 1939 numbers had grown to almost 400, most of whom had been recruited through labour groups and women’s branches of the co-operative movement. Every year, by ALRA’s estimation, some 90,000 women tried to induce an abortion without medical advice, often with fatal results.

Chance became one of ALRA’s most dedicated activists, haranguing small crowds from her soapbox on Hampstead Heath, funding the organisation’s running costs from her own resources, and on one occasion paying for 43,000 ALRA pamphlets to be sent to doctors across the country. In 1937 she gave evidence alongside Browne to the Inter-Departmental Birkett Committee on Abortion, telling the committee that ‘the working woman needs this relief more than her sisters’. Chance believed that the law should allow abortion when advised by a doctor on either medical or ‘social’ grounds, a right of especial value to financially insecure working women, and she was disappointed by the Birkett report which she described as ‘feeble’.

The outbreak of war in 1939 largely brought progressive campaigning to a halt. Chance, Browne, and Jenkins formed themselves into a skeleton committee to keep ALRA in being, but little could be achieved until the hostilities ended. Chance helped to find accommodation and work for refugee writers from Czechoslovakia, and then withdrew to her home in Hampshire where she wrote radio scripts for the BBC and raised chickens as her contribution to the war effort.

In 1945 ALRA changed direction, launching a campaign to secure a private member’s bill to legalise abortion. However, progress was slow and of the three members of the wartime ALRA committee only Jenkins lived to see the passage of David Steel’s Abortion Bill in 1967. Chance’s worsening mental health had forced her to resign as Chair of ALRA and in December 1953, while suffering severe depression following her husband’s death, she killed herself by jumping from a window.

The feminist historian Olive Banks described Janet Chance as ‘one of the most radical feminists of her generation’ while fellow humanist campaigner Madeleine Simms saw her as ‘a woman of great personal magnetism, with a capacity for inspiring devotion in all who worked with her’. Like many humanists in the women’s movement, Chance worked tirelessly for an unpopular but vital aim which was only realised after her death. Indeed, according to Jenkins, Chance thought of herself ‘as having been born at least a century too early’. Nevertheless, her energetic and devoted leadership of ALRA led ultimately to the passage of the Abortion Act 1967, which brought about a significant reduction in human suffering and thus a better world.

Janet Chance, The Cost of English Morals (1931)

Madeleine Simms and Keith Hindell, Abortion Law Reformed (1971)

Barbara L. Brookes, Abortion in England 1900-1967 (1988)

Janet Chance, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

By Paul Ewans

Founded in 1263, Balliol College is one of the oldest colleges at the University of Oxford. Established by the English […]

The object of this Society is: To increase the knowledge, the love, and the practice of the right. Its bond […]

The courage and steadfastness which lead thoughtful people to declare themselves openly Rationalists in face of conventional social pressure is […]

People have always looked for ways to mark significant events in their lives, and though many ceremonies have often been […]