We can’t help the universe, but at least we can do something to help ourselves. Can’t we?

John Boyd, Across the Bitter Sea: A Belfast Novel (2006)

John Boyd was a teacher, playwright, radio producer, and humanist, who wrote openly in his autobiographical works about his lack of religious belief. With other Belfast writers, including Forrest Reid and Sam Hanna Bell, Boyd played an active role in the city’s creative and cultural scene from the 1940s onwards, including as editor of literary journal Lagan, through his commissioning of programmes for the BBC in Northern Ireland, and as a writer. Of his birthplace he wrote:

Home was home. Belfast was Belfast. It was impossible for me to loosen the strings that bound me to the city. It was where I belonged and where I always would belong. And that is how it has been.

John Boyd, The Middle of My Journey (1990)

In his 1990 autobiography The Middle of My Journey, Boyd – a self-described ‘young agnostic male’ – recalls having ‘pleaded conscience’ when asked to lead prayers at the small Lisburn school he taught at. Later in the same book he wrote:

I had no religious faith, no belief in prayer, felt no need to worship a God or accept a creed. I suppose this should have cut me off, in some vital way, from many of my friends and acquaintances, but I do not think it did. I very seldom discussed religion with anyone except those whose attitude more or less coincided with my own – and this made for dullness – while to discuss it with fervent believers I always found a waste of time, like two people trying to conduct a debate but unable to understand each other’s language.

He recalls fondly, though, a close friendship with the Presbyterian minister Moore Wasson (‘We never discussed each other’s beliefs or nonbeliefs in organised religion, tacitly agreeing to respect each other’s views… and we also – very important this – enjoyed the same sense of humour’), and Canon Eric Elliott (‘the kind of religieux whose openmindedness I find stimulating; their convictions are, I think, based on a sense of certitude but they do not expect all their fellow creatures to have reached the same conclusions as themselves. Doubt is not a sin’).

In Across the Bitter Sea, a novel published posthumously in 2006, Boyd ends on a distinctly humanist note. In response to one character’s proclamation that ‘I think the whole universe is unjust… It’s a depressing thought, isn’t it?’, another replies simply: ‘We can’t help the universe, but at least we can do something to help ourselves. Can’t we?’

The biography reprinted below was first published in December 2013 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography, and revised in February 2019. It is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International license.

Contributed by Lunney, Linde

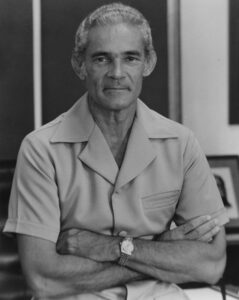

Boyd, John (1912–2002), radio producer and playwright, was born 19 July 1912 at 9 Baskin Street, in a working-class area of east Belfast, the first of three children (two boys and a girl) of Robert Boyd, a fireman on steam engines and later an engine driver, and Jane Boyd (née Leeman). The family, originally presbyterian, attended a congregational church. Robert Boyd was ambitious for his family, but eventually realised that his wife had a secret drink problem, and rows and recriminations were frequent while Boyd was growing up, with the youngster dragged in as a go-between. He attended Mountpottinger elementary school, where his abilities were recognised, and was pushed to win a scholarship to Royal Belfast Academical Institution, where he survived initial setbacks in an unfamiliar environment, and became very happy; he gained another scholarship which enabled him to attend QUB. His father, though bewildered by the student’s desultory lifestyle and lack of a definite career plan, supported him. However, John came close to quitting in his third year. An uncle and aunt, Willie and Ida Boyd, introduced him to the theatre and to classic texts of the labour movement, and this alternative education, along with socialist and second-hand bookshops and a wide circle of friendship, had much more appeal than the university.

An uncle and aunt, Willie and Ida Boyd, introduced him to the theatre and to classic texts of the labour movement, and this alternative education, along with socialist and second-hand bookshops and a wide circle of friendship, had much more appeal than the university.

After graduating in arts (at the beginning of the 1930s depression), he worked briefly in a factory in England, did some private tutoring, and then worked in an educational establishment run by the Ministry of Labour for unemployed school-age youths in Belfast. On 11 November 1939 he and Elizabeth McCune were married in Belfast; they were to have two sons and a daughter. For a few years, Boyd had a teaching job in Lisburn Intermediate school, working alongside Leslie McCracken (1914–2008); Boyd also taught in Belfast Royal Academy and adult education classes in Queen’s extramural department. He completed an extramural B.Litt. in TCD, with a thesis on the work of Forrest Reid (qv); with their Belfast settings, Reid’s novels, which Boyd had discovered when he was in school, inspired the younger man’s hopes of an Ulster-based literary career. In the early 1940s, Boyd had a number of articles published anonymously in the socialist and nationalist Irish Democrat newspaper, and then in 1943 with his friend Sam Hanna Bell (qv) founded a literary journal, Lagan. Though both editors held socialist views, neither was interested in the internationalist aspirations of communism; the issues of Lagan published from 1943–6 were intended to represent and foster local culture and writing. In January 1955 Boyd with a group including James Plunkett (qv) and Liam MacGabhann (qv) travelled on a three-week-long fact-finding trip to the USSR; the experience seems not to have been particularly satisfactory or enlightening for him.

As the second world war came to an end, the BBC reintroduced regional broadcasting, and in 1946 Boyd was encouraged to take up a post as producer of talks in the Belfast studios, joining Sam Hanna Bell there; they were the first senior, non-technical employees who were not members of the upper-middle class, and at the outset most of their colleagues were of English birth. At that period, the corporation’s editorial policies mirrored the social background of the executive; it was tacitly understood that BBC wireless programmes would deal almost exclusively with subjects intended to interest unionist listeners, and programme makers were expected to support the status quo. Boyd encountered obstructions and outright vetoes when he tried to introduce material which acknowledged the existence of an Irish dimension; it was also impossible for him to produce much of his own literary work or to be openly involved in political activity. Despite these difficulties, he found his quarter of a century in the BBC stimulating and engrossing; he met (and generally made friends with) almost everyone of significance in the province’s cultural and political life. Boyd produced Ulster commentaries, in which distinguished speakers analysed contemporary events, and he was also responsible for Your questions, a long-running series in which panel members answered questions from audiences in venues across the province.

Boyd’s interest in literature, and friendships with many authors from all over Ireland, brought about scores of programmes which preserved the voices and views of figures such as Seamus Heaney, Frank O’Connor, and Boyd’s school friend W. R. Rodgers.

Boyd’s careful selection of speakers made for interesting contrasts and for discussion of issues which had not been aired before on radio; panel members included James Joseph Campbell (qv) from the catholic community and Desmond G. Neill (d. 2004), a quaker academic, who was influential in attempts to foster community integration through social services and education. At the start of his career, Boyd had to seek permission to make programmes which featured historians such as his RBAI schoolfellows James C. Beckett (qv) and Theodore Moody (qv), and later he had to lobby to be allowed to sponsor the publication of three books of collected talks. Ulster since 1800, in two volumes (1954/5, 1957), edited by Moody and Beckett, and Belfast: the origin and growth of an industrial city (1967), edited by Beckett and R. E. Glasscock, were hugely important as pioneering surveys of a region where history was invoked more often than understood. Boyd’s interest in literature, and friendships with many authors from all over Ireland, brought about scores of programmes which preserved the voices and views of figures such as Seamus Heaney (1939–2013), Frank O’Connor (qv), and Boyd’s school friend W. R. Rodgers (qv).

From the late 1960s Boyd also produced some television programmes, but in 1972, aged 60, he retired from the BBC, planning to concentrate on his own writing. He had written a chapter on ‘Ulster prose’ for the 1951 compilation, The arts in Ulster (edited by Bell, John Hewitt (qv) and Nesca Robb (qv)), and adapted Mrs Martin’s man, a novel by St John Ervine (qv), for a production in the Group Theatre, in 1954. A play for radio, ‘The blood of Colonel Lamb’, was rejected as too controversial by the BBC, but was rewritten for the stage and put on by the Circle Theatre in the Belfast Festival of 1967. Another version, as ‘The assassin’, was performed in the Gaiety Theatre, Dublin, in 1969. John Boyd edited the Lyric Theatre’s literary journal Threshold from 1971, and in the 1970s was the Lyric’s literary adviser, encouraging up-and-coming dramatists like Stewart Parker (qv). As well as a version of Ibsen’s ‘Ghosts’ (1990, with an invited performance in Oslo later the same year), several of Boyd’s own plays were produced in the Lyric: ‘The farm’ (1972), ‘Guests’ (1974), ‘Facing north’ (1979), and ‘Speranza’s boy’ (1982), about Oscar Wilde (qv). ‘Summer class’ was performed in 1986, and ‘Round the big clock’ in 1992, when Boyd was 80. ‘The street’ (1977) was based on Boyd’s own family’s story.

Boyd’s most notable piece can be regarded as contributing to the development of a genre of dramatic work: plays about the Northern Ireland troubles. ‘The flats’ was the first play to be set in the province’s violence of the late twentieth century.

Boyd’s most notable piece can be regarded as contributing to the development of a genre of dramatic work: plays about the Northern Ireland troubles. ‘The flats’ was the first play to be set in the province’s violence of the late twentieth century. First performed by the Lyric Players in March 1971, it attracted capacity audiences; Fr Edward Daly put on an equally successful performance in Derry’s Little Theatre in holy week 1973, and the play was brought to Dublin’s Project theatre in May 1973. A television production was aired in 1975, and an Irish-language version was performed in Dublin in 1980. The play was revived in the Lyric in 1984. ‘The flats’ appealed to contemporary audiences perhaps partly because Boyd’s formulations reduced complexities. The depiction of the suffering of catholic and protestant neighbours did, however, have dramatic force, and the play permitted people to see the local conflict artistically distanced and as more emblematical than they had been able to do during the day-to-day descent into chaos of the late 1960s. Over the years, however, some of the tropes of ‘The flats’ turned up so often in work by other writers that they even attracted parody in a BBC Northern Ireland sitcom launched in the late 1990s, Give my head peace.

Literary scholars have not been particularly kind to Boyd’s dramatic works, and his later plays have not been granted even the status of historical interest accorded to ‘The flats’. Boyd’s literary reputation will probably rest on two volumes of autobiography, Out of my class (1985) and The middle of my journey (1990), and for his compilation of a huge accompanying archive of material about a life spent in a cultural milieu of continuing interest to literary historians. It appears, for instance, that Boyd’s unofficial tape of Frank O’Connor talking about his own childhood is a unique survival, as the BBC destroyed original programme recordings. The archive, including Boyd’s manuscripts as well as those of other authors, has been placed in the Linen Hall Library in Belfast. A novel, Across the bitter sea, was published posthumously in 2006; it was edited from Boyd’s manuscripts in the archive.

Boyd should be acknowledged as one of the most influential of the small number of mid-twentieth-century people in Northern Ireland who were sometimes able to step outside the locally constructed boxes. Though more shaped by his background than he was able to acknowledge, his ability to make friends in all areas of life and across boundaries was important in a role in which he could facilitate province-wide discussions on previously ignored matters.

Boyd died in Belfast in July 2002, just before his ninetieth birthday. After his death, his family gave a number of important books of his collection to the Irish people, including a second edition of Ulysses by James Joyce (qv), which Boyd had smuggled into Ireland hidden in a box marked ‘sanitary towels’ to circumvent its seizure by Irish customs officials as an obscene publication. Alongside the important legacy of his autobiographical writing and his archive, Boyd should be acknowledged as one of the most influential of the small number of mid-twentieth-century people in Northern Ireland who were sometimes able to step outside the locally constructed boxes. Though more shaped by his background than he was able to acknowledge, his ability to make friends in all areas of life and across boundaries was important in a role in which he could facilitate province-wide discussions on previously ignored matters.

Ir. Times, passim, esp.: 17 Jan. 1955; 30 Apr. 1973; Ir. Independent, passim, esp. 30 Apr. 1973; John Boyd, Out of my class (1985); id., The middle of my journey (1990); Louis Muinzer, ‘Between the world and the stage: a tribute to John Boyd’, Fortnight, cdxiii (Apr. 2003), 19; Jonathan Bardon, Beyond the studio: a history of BBC Northern Ireland (2000), passim, esp. p. 205; Guardian, 5 Oct. 2002; Christopher Morash, A history of Irish theatre 1601–2000 (2002), 245; Tom Maguire, Making theatre in Northern Ireland: through and beyond the Troubles (2006), 22, 159; Bruce Stewart (comp.), ‘John Boyd (1912–2002)’, Ricorso, www.ricorso.net; Shirley Bork, ‘John Boyd: teacher, playwright, radio producer’, www.belfastgalleries.com/article.aspx?art_id=1167 (internet material accessed Aug. 2013)

John Boyd | The Northern Ireland Literary Archive

Indian social and religious reformer Rammohun Roy is sometimes referred to as the ‘father of modern India’: a progressive thinker, […]

…the only efficient, the only decent prayer, is Action. John Galsworthy, ‘Philosophy of Life’ in Glimpses and Reflections (1937) Best […]

I like life with its mysteries. I don’t need my imponderables filled in for me. Michael Manley quoted by Rachel […]

Love is a kind of courage, and, in the hearts of the man and woman who will here wed, there […]