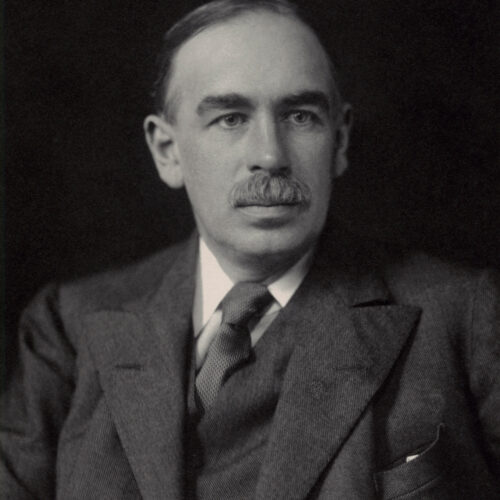

Words ought to be a little wild, for they are the assault of thoughts upon the unthinking.

J.M. Keynes in New Statesman and Nation, 15 July 1933

John Maynard Keynes was one of the most influential economists of the 20th century, and – like many in the Bloomsbury Group of which he was a part – embodied a humanist approach to living. As well as being a prominent theorist, he put his economic ideas into action through roles such as Director of the Bank of England during the Second World War. He was also a major patron of the arts, serving as the first Chair of the Committee for Encouragement of Music and the Arts (now Arts Council England), and founding the Cambridge Arts Theatre.

Our apprehension of good was exactly the same as our apprehension of green, and we purported to handle it with the same logical and analytical technique which was appropriate to the latter.

‘My Early Beliefs’, a paper presented by J.M. Keynes to Bloomsberries gathered at his country house on 9 September 1938

John Maynard Keynes was born on 5 June 1883 at 6 Harvey Road, Cambridge. Keynes’ father, John Neville Keynes, was an economist and later an academic administrator at King’s College, Cambridge. His mother, Florence Ada Keynes, was one of the first female Cambridge graduates and went on to become the first female councillor of Cambridge City Council. J.M. Keynes was educated at Eton and enrolled at Cambridge in 1902, while his father lectured there in moral sciences.

The writer Lytton Strachey, who had entered Cambridge two years before Keynes, inducted the younger man into the Cambridge Heretics – a group of writers and artists who opposed compulsory worship and celebrated humanist values like freethought, counting other prominent humanists like Virginia Woolf and Bertrand Russell among their members. A key influence on the society was the philosopher and President of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK), George Edward Moore. Moore argued in Principia Ethica (1903) for the value of ‘the pleasures of human intercourse and the enjoyment of beautiful objects’ as the central guiding force of morality.

Many of the Cambridge Heretics went on to form the Bloomsbury Group – a collective who consciously eschewed many of the Victorian social norms they had been born into, adopting instead a humanist worldview which celebrated equality and freedom, believing that everyone had the right to live and love as they chose. Keynes was bisexual. His early relationships were exclusively with men, and many of his lovers (including Bloomsbury Group members) Lytton Strachey and Duncan Grant) became lifelong friends. These companionships continued long after his marriage to the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova in 1925.

Keynes worked for the Treasury during the First World War, and his experiences at the 1918 Versailles Peace Conference led him to challenge conventional economic thinking with his ground-breaking 1919 book The Economic Consequences of the Peace. A series of books followed, forming the basis of what is now known as Keynesian Economics.

While professionally focused on economic theory, his personal literary interests remained inclined towards the humanist ethics of Moore, which in 1938 Keynes described as ‘still my religion under the surface’. During his time as Director of the Bank of England in the Second World War, Keynes was foundational in establishing Arts Council England, demonstrating his commitment to both economic reform and Moore’s ethical impetus towards objects of beauty.

This achievement, the creation of the Arts Council in time of war, of a war in which he was playing an important and exhausting part, proves – but again what need of proof? – his boundless energy and versatility, as well as his capacity for making something solid and durable out of a hint.

Clive Bell, writing about J.M. Keynes

Keynes’ support of the arts went through and beyond his personal relationships. Alongside fellow Bloomsbury Group member George ‘Dadie’ Rylands, Keynes devised a plan for a modern theatre in central Cambridge, securing a lease of land from King’s College in 1936. Thanks to donations from Bloomsberries like E.M. Forster (who was also a longtime Vice President of the British Humanist Association, now Humanists UK), the Cambridge Arts Theatre opened to great success and continues to operate today. Keynes also was foundational in establishing the London Artists’ Association and the National Gallery’s collection of modern French painting.

In 1946, Keynes returned ill from an International Monetary Conference in America and died of a heart attack at his country house in Sussex.

…one of the most remarkable men that ever lived. The quick logic, the bird-like swoop of intuition, the vivid fancy, the wide vision, above all the incomparable sense of the fitness of words, all combine to make something several degrees beyond the limit of ordinary human achievement.

Lionel Robbins, The wartime diaries of Lionel Robbins and James Meade, 1943–45 (1990)

Probably the most influential economist of the 20th century, John Maynard Keynes was so much more besides. A key member of the freethinking Bloomsbury Group, he was a lifelong lover – and active promoter – of the arts, using his financial aptitude, personal connections, and persuasive character to create, foster, and sometimes to rescue art organisations of many kinds. In the words of art critic and close friend Clive Bell, Keynes ‘was one of those uncommon human beings who have devoted great powers of organization to good purposes. Maynard’s gifts were always at the service of civilization’.

John Maynard Keynes is one of the historical figures featured in Picturing Nonconformity: LGBT Humanist Heritage, created for the 45th anniversary of LGBT Humanists in 2024. Explore the exhibition.

Main image: John Maynard Keynes, Baron Keynes by Walter Stoneman, 1930 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Positivism is a philosophical system based on the writings of French thinker Auguste Comte, which flourished from the 1830s onwards. […]

The Liverpool Ethical Society was founded in 1904, and in 1912 Liverpool became home to one of only a handful […]

I have been the more bold in exposing my opinion because I believe it to be the dictates of truth […]

With these basic [humanist] beliefs there go commonly two corollaries. First, that virtue is a matter of promoting human well-being, […]