Can there be a more important human condition than dignity? Without it, we are bitter, downtrodden, unheard, humiliated, embarrassed and disempowered. With dignity, we are peaceful, collegial, kind, compassionate and even at times cohesive.

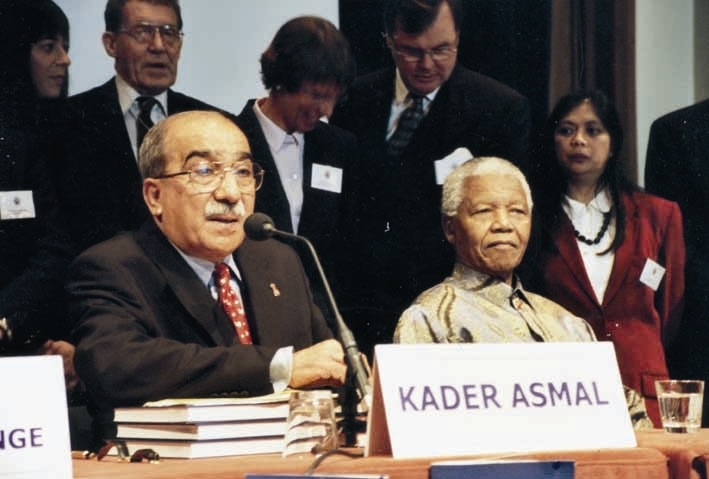

Kader Asmal, Politics in My Blood: a Memoir (2011)

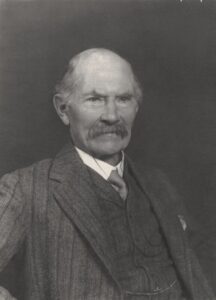

Kader Asmal was a South African politician, professor, and human rights activist. A co-founder of both the British and Irish anti-apartheid movements, he was also a founder and later President of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties. Asmal was a lifelong champion of human liberation, and helped to shape a new constitution for South Africa as part of the African National Congress’ executive committee. Asmal spent many years of his life living and working in England and Ireland, and in 1969 was a key participant in the First Conference of Humanists in Ireland. With the political philosopher Alan Milne, he proposed a resolution there which included the assertion that ‘the attainment of the civil rights and liberties accepted in a normal democratic society should be effectively secured without reference to race, sex, religion or political affiliation both in the North and South [of Ireland]’ – a principle he worked for internationally, throughout his life.

The biography reprinted below was first published in June 2018 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography. It is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International license.

Contributed by Maume, Patrick

Asmal, (Abdul) Kader (1934–2011), human rights jurist, anti-apartheid campaigner and South African government minister, was born on 8 October 1934 in Stanger (KwaDukuza), Natal, South Africa, the youngest of eight children (six sons and two daughters) of Ahmed Asmal, grocer, and his wife Rasool. Ahmed had migrated from Gujarat; he was one of the less prosperous members of a Muslim extended-family network, several of whom were successful businessmen. Kader’s recollections display intense love for his father and (illiterate) mother, who were intellectually curious and saw education as the way forward for their children. He was increasingly irritated by the constraints of the Indian Muslim community (a sister was withdrawn from school aged 12 after conservative Muslims threatened to boycott the family shop, and richer members of the clan took a grudging and patronising attitude to the Asmals) and by racial discrimination imposed by white South African governments.

Kader’s recollections display intense love for his father and (illiterate) mother, who were intellectually curious and saw education as the way forward for their children. He was increasingly irritated by the constraints of the Indian Muslim community… and by racial discrimination imposed by white South African governments.

A physically frail child who suffered from asthma and did not go to school until he was 9, the bookish Kader learned much from overheard conversations in his father’s shop. At age 12 he was secretary to a local Indian cricket club and wrote letters for illiterate traders. Between the ages of 9 and 18 he attended Stanger Indian Secondary School, dominated by brutal unqualified teachers, rote learning, and the abjectly impoverished children of sugar plantation labourers (the majority of the Indian community). As a schoolboy he befriended and deeply admired the African National Congress (ANC) leader Albert Luthuli (1898–1967), who led him to see himself as part of a wider South African nation.

Racial discrimination intensified after 1948 when the National Party won power and implemented its apartheid policy, aimed at entrenching racial separation and white advantage. Asmal witnessed harsh punishment of leaders of the Natal Indian Congress (allied to the ANC) for joining the ANC’s 1952 ‘defiance campaign’ (refusal to carry passbooks which regulated work and residence restrictions imposed on non-whites). He joined the campaign and acted as secretary to a ratepayers’ association.

In 1952 he went to Springfield Teachers’ Training College in Durban, where he grew more politically active and socialised extensively outside the Asian community. He became an atheist, though in Stanger he attended Islamic services until his father’s death in 1958.

In 1952 he went to Springfield Teachers’ Training College in Durban, where he grew more politically active and socialised extensively outside the Asian community. He became an atheist, though in Stanger he attended Islamic services until his father’s death in 1958. After qualification in 1954, Asmal was assigned to an Indian school in the sugarmill-dominated company town of Darnall (commuting from Stanger), and was later transferred to a school in Stanger. He studied for a BA by correspondence in English, politics and history from the University of South Africa. His reading, the exploitation he observed around him, and the apartheid regime’s appeals to anti-communism were influences that converted him to Marxism. Becoming disenchanted with teaching as the government drastically restricted curricula for non-whites, he decided to retrain as a barrister and defend human rights cases.

With family help, he travelled in 1958 to Britain and studied law at the London School of Economics, winning a scholarship after his first-year exams. Influenced by the barrister, anti-colonialist and former far-left Labour MP D. N. Pritt (1887–1972), he chose to join the broad-left Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers rather than the Society of Labour Lawyers. Asmal was critical of liberal theories of law that limited the state’s role to preserving individual liberty rather than correcting structural injustices and inequality, and despised gradualist definitions of politics as ‘the art of the possible’. He graduated BL (1962) and LLM (1964), and qualified for the bar at Lincoln’s Inn.

He began working with the ANC… and joined the underground South African Communist Party (SACP)… His intense identification with the dispossessed masses, and belief that popular struggle must be led by a disciplined vanguard group, reflected his Marxism.

He began working with the ANC (although he could not become a formal member until 1986) and joined the underground South African Communist Party (SACP). Remaining a member of the SACP until 1991, he always denied claims that it secretly directed the ANC. His intense identification with the dispossessed masses, and belief that popular struggle must be led by a disciplined vanguard group, reflected his Marxism (though he, and the ANC, placed more emphasis on internal debate and consensus than classical Leninists). Some of his subsequent students thought him uncritical of the Soviet bloc, and Mary Manning, leader of the Dunnes Stores anti-apartheid strike (1984–7), which led to a ban on the importation of South African produce to Ireland, thought that while the strike could not have succeeded without Asmal’s advice and encouragement, he was uncomfortable with self-organised working-class action not coordinated from above.

After the killing of sixty-nine demonstrators at Sharpeville by South African police (21 March 1960), government repression intensified. In response, the ANC and other movements shifted from non-violent protest to armed resistance (a trend Asmal initially opposed). He was a founding committee member (20 April 1960) of Britain’s Anti-Apartheid Movement, and became active in London demonstrations. His passport was cancelled and his family in Natal harassed.

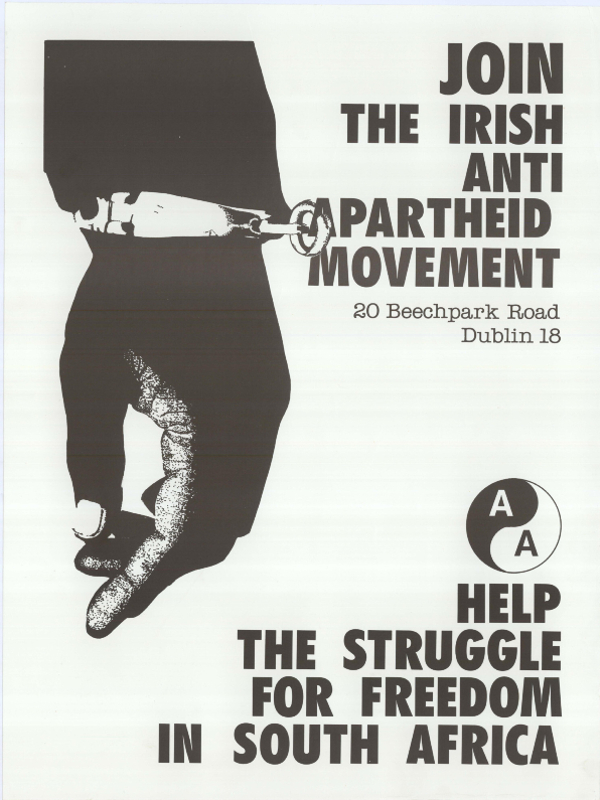

He was a founding committee member (20 April 1960) of Britain’s Anti-Apartheid Movement, and became active in London demonstrations. His passport was cancelled and his family in Natal harassed… The Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement (IAAM) was launched in April 1964; Asmal was the mainstay from its inception, and later chairman (1972–91).

Asmal married (30 December 1961) Louise Parkinson, an activist with the National Council for Civil Liberties. Since Louise was white, this excluded Asmal from South Africa, where inter-racial marriages were prohibited and it was a criminal offence for mixed-race couples to cohabit. They had two sons, and were political associates and co-workers throughout their long and affectionate marriage. In 1962 Asmal applied for a position in the faculty of law at the University of Ghana. This brought him to the attention of Conor Cruise O’Brien, who recommended him for a vacant law lectureship in Trinity College Dublin. Asmal was advised to accept by the exiled ANC leader Oliver Tambo (1917–93) so as to organise anti-apartheid activism in Ireland.

The Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement (IAAM) was launched in April 1964; Asmal was the mainstay from its inception, and later chairman (1972–91). He regularly gave speeches and wrote for Irish newspapers to publicise the evils of apartheid. The IAAM mounted a series of campaigns against Irish contacts with the apartheid state, including a high-profile protest against the 1970 visit of the Springboks rugby team to Ireland and subsequent visits to South Africa by Irish sportsmen and musicians. It put pressure on successive governments to enforce the economic and cultural boycott and international isolation advocated by the ANC. Asmal acted as legal adviser to the exiled South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee and similar bodies. The importance of his role as jurist and theorist within the ANC was often unrecognised by those who only knew him in the Irish context. He also took a prominent role in the clandestine international network that transmitted money to support the families of political prisoners and paid for legal representation.

Asmal acted as legal adviser to the exiled South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee and similar bodies. The importance of his role as jurist and theorist within the ANC was often unrecognised by those who only knew him in the Irish context. He also took a prominent role in the clandestine international network that transmitted money to support the families of political prisoners and paid for legal representation.

Asmal’s deep and lifelong love of English-language literature included fascination with the Irish literary tradition, partly because of its evocations of exile and Irish nationalist struggle against Britain; he mixed extensively in Irish social and literary circles, assisted by his fondness for Irish whiskey. His articulacy, personal charm and fierce commitment were crucial to the development of large-scale popular support for the anti-apartheid movement. (It should be noted, however, that much of the Irish population dismissed him as a politically dubious crank.)

A well-known personality on the TCD campus, Asmal was dean of the faculty of arts (1980–86). Taking a personal interest in students’ well-being, he actively encouraged discussions (frequently joining impromptu student forums on the dining hall steps) and was an impassioned if digressive lecturer. In the early 1980s he advised and publicly identified with opponents of Ireland’s legal and constitutional prohibition on abortion. He was generally more an activist than a scholar (despite publishing 150 academic papers), and his office became a centre for his political activities. He provided extensive legal advice to Irish trade unions, a bastion of support for the IAAM, and in 1965 co-founded the Irish Federation of University Teachers (president, 1974–5).

Asmal was a co-founder in 1976 of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties, serving as president (1976–90), and was awarded an UNESCO prize for development and teaching of human rights (1985). He also participated in UN inquiries on the crimes of the apartheid regime and violations of international law by Israel.

Asmal was extremely critical of the human rights record of the Fine Gael–Labour coalition government of 1973–7 (which included Cruise O’Brien). When Taoiseach Liam Cosgrave (1920–2017) denounced ‘blow-ins … not even Irish’, Asmal was one obvious target. Asmal was a co-founder in 1976 of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties, serving as president (1976–90), and was awarded an UNESCO prize for development and teaching of human rights (1985). He also participated in UN inquiries on the crimes of the apartheid regime and violations of international law by Israel.

Suspicions of Asmal in some quarters were encouraged by his sympathy for Irish republicanism, and he regarded the Northern Ireland troubles as essentially colonial. In preparation for a high-profile 1980 bombing attack on the principal South African oil refinery by the ANC’s armed wing, he arranged for IRA personnel to provide explosives training and to reconnoitre the target. He chaired an international group of left-wing lawyers that held an unofficial inquiry into shootings of civilians by the Northern Ireland security services (1985). His D. N. Pritt lecture (1989) to the Haldane Society (published as If law is the enemy…), which argued that British lawyers should oppose state human-rights abuses in Northern Ireland, led to the creation of the pressure group British Irish Rights Watch. In 1984 Asmal’s willingness to affiliate Sinn Féin to the IAAM alienated some members, including the taoiseach, Garret FitzGerald. This formed part of the backdrop to a large-scale 1986 controversy between Asmal and Cruise O’Brien (formerly chair of the IAAM) over the latter’s acceptance of a temporary lectureship at the University of Cape Town. Asmal accused O’Brien of assisting the apartheid regime, while O’Brien accused Asmal of denying academic freedom, encouraging the threatening demonstrations that led to cancellation of O’Brien’s lectures, displaying a dictatorial mentality, and pandering to republican opinion.

He chaired an international group of left-wing lawyers that held an unofficial inquiry into shootings of civilians by the Northern Ireland security services (1985). His D. N. Pritt lecture (1989) to the Haldane Society (published as If law is the enemy…), which argued that British lawyers should oppose state human-rights abuses in Northern Ireland, led to the creation of the pressure group British Irish Rights Watch.

After the 1990 release from prison of Nelson Mandela (1918–2013) and the unbanning of the ANC, Asmal returned to South Africa in 1991, taking up a position in human rights law at the University of the Western Cape. He was elected to the ANC national executive council (1991–2007) and was an ANC delegate at the 1993 multi-party negotiating forum, which negotiated replacement of white minority rule by a system based on universal suffrage. Asmal, who had earlier drawn up a series of constitutional principles as framework for the ANC’s negotiating position, played a major role in drafting the new South African constitution. After Tambo’s death in 1993, Mandela (now ANC president) favoured Asmal as ANC chairman, but did not receive sufficient support within the ANC organisation.

Asmal, who had earlier drawn up a series of constitutional principles as framework for the ANC’s negotiating position, played a major role in drafting the new South African constitution… After the first democratic South African elections led to the creation of a multi-racial government of national unity in May 1994, Asmal became minister for water affairs and forestry.

After the first democratic South African elections led to the creation of a multi-racial government of national unity in May 1994, Asmal became minister for water affairs and forestry. (President Mandela had wished to appoint him as minister for constitutional development, but the National Party requested the position.) Asmal vigorously extended sanitation and water supplies to previously excluded rural areas, while outlawing private monopolies of water sources and emphasising water conservation rather than the engineering-centred approach of the apartheid regime (which favoured urban whites, white farmers, and industry). In 2000 he became the first non-scientist awarded the Stockholm Water Prize. Asmal’s approach to government was founded on fierce attention to detail and willingness to argue his case; he claimed he was one of only four ministers (including Thabo Mbeki, Mandela’s deputy and successor) who prepared for cabinet meetings by reading all the relevant documentation, and he ranged so extensively he became known as ‘minister of all portfolios’ (Asmal (2011), ix).

[As minister for education, Asmal’s] tasks included introduction of a new child-centred curriculum, promotion of literacy, removal of religious education from state schools (despite criticism), and a controversial restructuring of the under-resourced higher education system, including affirmative action in appointments.

Though he was diagnosed with bone marrow cancer in 1998, Asmal was appointed minister for education by President Mbeki the following year. His tasks included introduction of a new child-centred curriculum, promotion of literacy, removal of religious education from state schools (despite criticism), and a controversial restructuring of the under-resourced higher education system, including affirmative action in appointments. Asmal was not close to Mbeki (whom he thought brilliant but authoritarian) as he had been to Mandela, and later criticised some of Mbeki’s policies, including his disastrous view that AIDS was a disease of poverty not necessarily caused by the HIV virus. He left government at Mbeki’s request in 2004, but remained a member of the South African parliament until he resigned in February 2008 in protest at the proposed disbanding of an elite anti-corruption unit (involved in the struggle between Mbeki and his eventual successor Jacob Zuma). Asmal was widely perceived as the conscience of the ANC for his criticism of corruption and ethnic politicking; weeks before his death he denounced proposals to penalise publication of sensitive information.

Asmal was widely perceived as the conscience of the ANC for his criticism of corruption and ethnic politicking; weeks before his death he denounced proposals to penalise publication of sensitive information.

After retiring from politics, Asmal held a number of academic posts in South Africa, and served on bodies investigating dams, money laundering, and the arms trade. He regularly visited Ireland (‘my second home’) to receive honorary degrees (from TCD, QUB and UCG; he was also a fellow of the RCSI), to promote human rights causes (including advocacy of same-sex marriage), and to commemorate events such as the Dunnes strike. In his last year, as his health declined, he compiled a series of autobiographical reflections, edited and completed by Louise after his death. He died of a heart attack in Cape Town on 22 June 2011. TCD instituted a Kader Asmal fellowship for South African students in 2012.

Ir. Times, 21 Apr. 1964; 10 Dec. 1965; 12 May, 11 June, 7 Sept., 14 Oct., 12 Nov. 1966; 23, 28 Jan., 2, 6, 25 Feb. 1967; 25 June 2011; Sunday Independent, 3 Dec. 1972; 29 June 2001; 26 June 2011; 8, 15 Dec. 2013; Ir. Independent, 6 June 1979; 12 July 1991; 4 July 1998; 23 Mar., 25 Sept. 2000; 28 June, 30 Aug. 2003; 23 May 2006; 7 Dec. 2013; Ir. Press, 31 Dec. 1983; 11 July 1987; 12, 21 Feb., 7 June 1990; Kader Asmal (chair), Shoot to kill?: International Lawyers’ Inquiry into the Lethal Use of Firearms by the Security Forces in Northern Ireland (1985); Conor Cruise O’Brien, Passion and cunning, and other essays (1988); Kader Asmal, If law is the enemy…: human rights in Northern Ireland: Britain’s responsibilities (1990); Irish [Cork] Examiner, 2 June 1990; 9 Aug. 1993; 7 July 1998; 31 Mar. 2003; 24 Apr. 2004; 23 May 2006; 11 Feb. 2010; Munster Express, 16 Dec. 1994; City Tribune (Galway), 20 Feb. 1998; 17 Nov. 2017; Guardian, 23 June 2011; Independent (London), 28 June 2011; Kader Asmal, with Adrian Holland and Moira Levy, Politics in my blood: a memoir (2011); Kathy Gilfillan (ed.), Trinity tales: Trinity College Dublin in the seventies (2011); Mary Manning, Striking back: the untold story of an anti-apartheid striker (2017); Nelson Mandela and Mandla Langa, Dare not linger: the presidential years (2017)

Free thought means fearless thought. It is not deterred by legal penalties, nor by spiritual consequences. Dissent from the Bible […]

Oh what a tissue of inconsistencies are the dogmas in which we have been reared! Emma Martin, God’s Gifts and […]

The Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK) was formed in 1896, joining together existing ethical societies for fellowship and […]

Throughout his life, Professor of Philosophy, John Muirhead, sought to put his ethical principles into practice. Indeed, whilst philosophers are […]