Lillie Boileau was a devoted figure within the Ethical movement, and an active part of the fight for women’s suffrage. Described as having a ‘charming personality’, Boileau was nonetheless unafraid of taking a strong stand for the causes she believed in; arrested twice for her part in campaigning with the Women’s Freedom League. A key presence for three decades in the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK), and in its Women’s Group, Boileau testifies to the vital role of women in the early organised humanist movement, and to the work of those within it for real social and political change.

Lillie Mabel Boileau was born 4 April 1869, in Purayh, India, to retired army general Neil Edmonstone Boileau and Irish-born Mary Catherine Elizabeth Flemyng. Following the death of her father in 1895, Lillie moved with her mother and sisters to England, where they settled permanently.

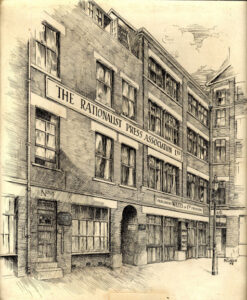

Boileau was active in the Ethical movement for over thirty years, joining its council in 1906, and helping to found its Women’s Group in 1915. In 1923, she was elected to represent the latter at the annual Congress of the Ethical Union. For over a decade, 1915-1926, she acted as literature agent for the Union. For some years, Boileau also took charge of catering at the Emerson Club, on the premises of the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK).

As well as playing a central role in the burgeoning humanist movement, Lillie Boileau was an active suffragist throughout her life. She was a founding member of the Women’s Freedom League, which was formed at the Emerson Club by a dissenting group from the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). The Women’s Freedom League had a strongly humanist element, and many of its members – notably Teresa Billington-Greig and Alison Neilans – were also connected to the ethical societies.

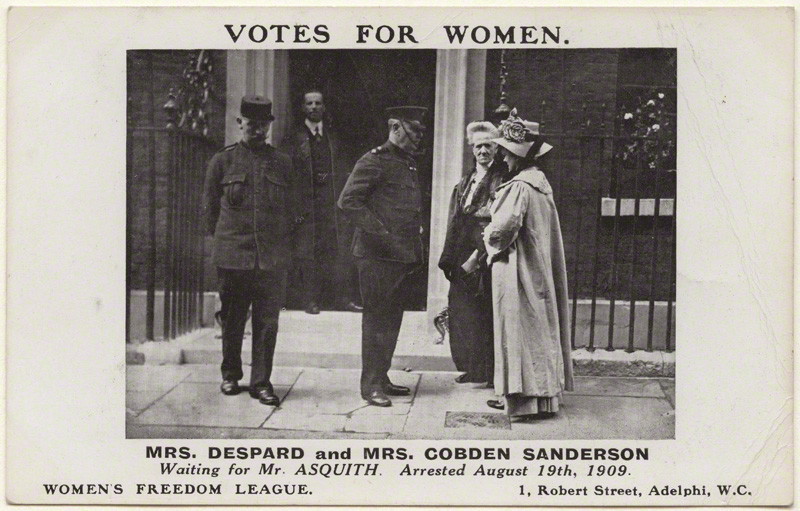

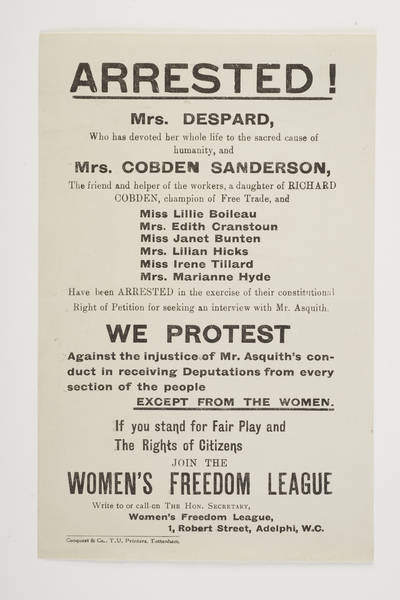

On 19 August 1909, along with WFL leader Charlotte Despard and other members, Lillie Boileau was arrested attempting to present a suffrage petition to Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith. The incident was widely reported, and Boileau was accused of throwing ‘a cardboard roll containing a petition’ at Asquith. She protested her innocence of this charge, writing:

When Mr Asquith drove up to 10, Downing-street, at 12.15 a.m., Miss Bunton and I were quietly sitting on the pavement; we were immediately pushed away, and a cordon of police placed themselves between us and the Prime Minister. I had waited four hours that evening to personally present my petition to him, and in he endeavour to do so under these difficult circumstances, I raised my arm to reach over the shoulders of the police in front of me – my wrist was immediately seized from behind by a plain clothes officer with such force that the roll flew out of my hand and fell, as described, into the gutter behind Mr Asquith. I may add that our sole purpose in being in Downing-street was to personally hand our petition to Mr Asquith, and that object could in no way have been attained by throwing it as suggested.

After the Representation of the People Act of 1918 gave some women the right to vote, excluding those under 30 and without property, she continued her efforts to gain suffrage on equal terms for all. She became the Honorary Secretary of the St. Pancras Society for Equal Citizenship, and mobilised the Women’s Group of the Ethical Movement in marching for the cause. When the second Act was passed in 1928, granting fully equal franchise, Boileau continued to organise meetings discussing women’s rights, including in areas of policing, factory legislation, housing, and international issues.

Lillie Boileau died on 15 August 1930, ‘whilst engaged in tending the flowers in her old-world garden at Highgate’, and was cremated at Golders Green. The ceremony was conducted by friend and fellow humanist Harry Snell, who said:

Her life was useful and commendable; she was gentle, with a firm will; she had a strong mind which was not yet closed or narrow, and, above all, not vague nor undecided. She had administrative gifts of a high order, and a tried and practical wisdom. She was a great servant and a great lady.

In her, the Ethical Union found one of its most intelligent, loyal and sympathetic collaborators.

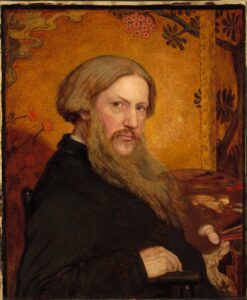

Gustav Spiller

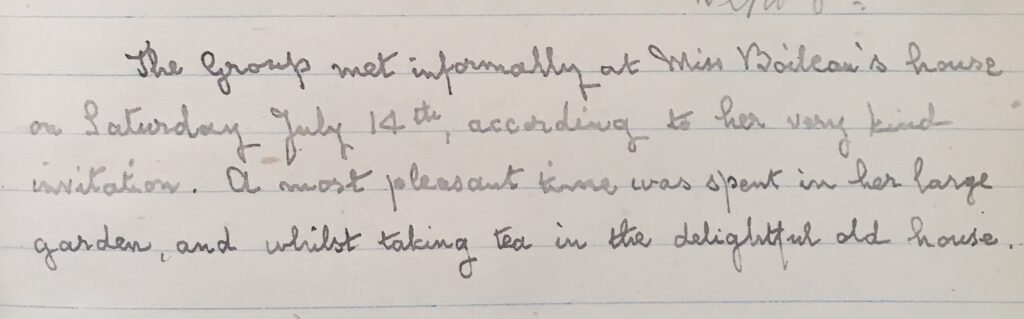

Lillie Boileau is a powerful example of the kind of woman who sat central to the organised humanist movement at the beginning of the 20th century. A passionate and progressive freethinker, she worked actively to support the development of the Ethical movement, and to further the cause of equality through women’s suffrage. As well as activism and organisation, Boileau was a key part of the social life of the movement, frequently hosting meetings of the Women’s Group at her home, and playing an active role in the life of the Emerson Club. Although her name has been little remembered, her character, talents, and contributions to both humanism and suffrage were lauded by those who knew her in life, and form a notable part of both histories.

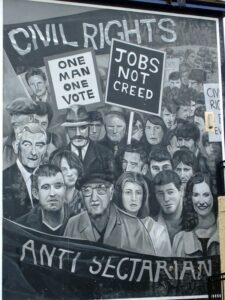

A brief history of humanism and secularism in Northern Ireland Organised humanism began in Northern Ireland in the 19th century, […]

Rationalism is not a dogma but a method. It does not tell us what to believe but how to find […]

A cheerful and reverent Agnostic, whose whole life was one of unselfishness and devotion to lofty aims, who was tolerant […]

Life would be far more truly envisaged if we dropped the silly phrases “men’s and women’s questions”; for indeed there […]