It has been suggested that matter is capable of destruction, that every atom is destined to be dissolved away in radiation. The possible annihilation of matter, the possible annihilation of the ultimate elements of the universe – here indeed is a hypothesis upon which to found the philosophy of our lives.

Llewelyn Powys, Impassioned Clay (1931)

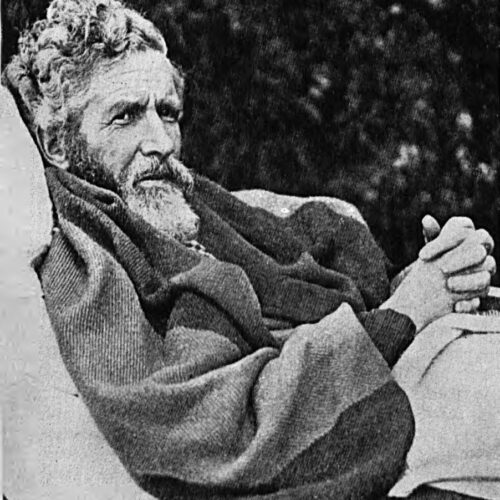

Llewelyn Powys was a writer and humanist, sometimes described as ‘the Dorset Epicurean’. Writing in The Humanist twenty-five years after his death, Evelyn Scott Brown recalled Powys as ‘a unique personality with an exhilarating philosophy of exultant life-worship,’ and ‘one of the brightest, happiest, [and] most gloriously courageous’ of humanists. Powys wrote and published prolifically, including for The Literary Guide (now the New Humanist) and The Rationalist Annual, giving shape to an infectiously joyful vision of goodness without god.

Merely to be alive should be sufficient reason for happiness… Always we should be taught to be conscious and more conscious, to be accessible to ideas, to be receptive to sense impressions… We should come from our schools fortified against mischance, knowing that nothing matters as long as we remain healthy and alive.

Llewellyn Powys, ‘Natural Happiness’ in The Rationalist Annual (1933)

Llewelyn Powys was born in Dorchester, Dorset, the son of a vicar. Sensitive to the natural world and evidently intelligent, he nevertheless did not excel academically, having to sit his final exams at the University of Cambridge twice to obtain his BA. Powys worked for some years as a schoolteacher, before a serious haemorrhage confined him to a sanatorium for sixteen months. He used this time to read widely and to hone his writing, first experiencing the cycle of ill health, convalescence, and remarkable productivity which would colour his life. Alyse Gregory would later write:

From resolute death, always ambushed near, he never removed his eye. It was in this forced state of heightened awareness that he passed his hours, celebrating with ever-renewed astonishment the miracle of another day.

Alyse Gregory, ‘Llewelyn Powys’ in The Literary Guide (1940)

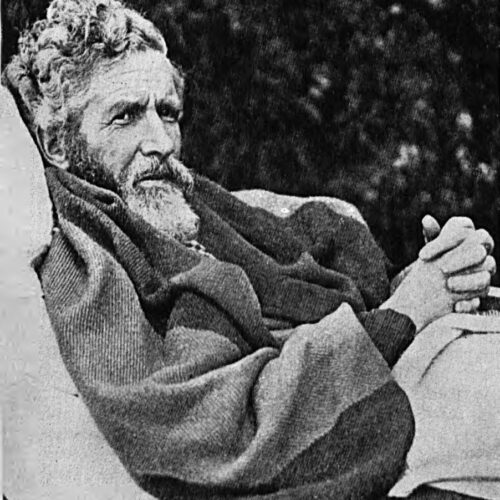

Powys turned away from Christianity early, drawn instead to the philosophy of Epicurus. The emphasis on living well with others, the pursuit of pleasure, and the attainment of happiness, resonated with Powys, and established the life-affirming outlook which stayed with him. As to Christianity he would later write:

During my whole life I do not believe I have ever experienced a genuine religious emotion that might with justice be described as Christian.

‘How I Became and Why I Remain a Rationalist’ in The Rationalist Annual (1937)

What Powys did experience was an unending sense of wonder at the universe, and marvel at the fact of being alive. In the same essay, he expressed his belief that ‘the secret of sound human thinking is to be found in an unequivocal acceptance of the basic truth that man is but an ephemeral animal on an inconsequent planet.’ Powys always clung to this absolute belief in making the most of existence. His Epicurean tenets Powys summed up in an article for The Rationalist Annual:

I believe in no God.

I believe in no immortality.

I believe that the secret of life is happiness.

I believe that virtue is heathen goodness.

Powys believed that morality arose from compassion, human sympathy, and a sense of life’s brevity. He rejected notions of morality as rooted in religion, writing:

Goodness that relies upon a ghost is not to be trusted; goodness should be as natural as sunshine and as undiscriminating… Look up at the moon, at the planets, at the sun, at the Milky Way, at the remotest nebula, and know well that our concern is, and should always be, here and now.

Llewelyn Powys, ‘A Foot-path Way of the Senses’ in The Rationalist Annual (1940)

Powys spent a number of years in America, where he met and married writer and editor Alyse Gregory, in 1924. The two returned to England, and settled in a coastguard cottage in Dorset, later moving to Chydyok, another coastal cottage. For much of the 1930s, Powys suffered recurring ill health, but maintained a prolific literary output. In 1936, the couple travelled to Clavadel, Switzerland, hoping to improve Powys’ health. He died there on 2 December 1939, and was cremated. In a letter written during his final illness, Powys was accepting. ‘I am not as well,’ he wrote, ‘but have had a happy life for half a century in the sunshine’.

Our vaunted minds are nothing but the senses in flower. When the senses wither and die the mind withers and dies with them.

Llewellyn Powys, ‘Natural Happiness’ in The Rationalist Annual (1933)

I was a cuckoo whose tune no June ever changed. “Love life! Love life! Love life!” was all my song.

Llewelyn Powys, ‘A Foot-path Way of the Senses’ in The Rationalist Annual (1940)

Powys left behind a prodigious literary output, and a vivid expression of the humanist philosophy, rich with the influence of classical thinkers, and imbued with a love of life. In his many pieces for The Literary Guide and Rationalist Annual, we see a passionate defence of the rationalist approach, underpinned by an embrace of marvel and mystery. In 1935, John Rowland described Powys’ lifelong philosophy:

If our world comes down tumbling around our ears, let us not forget what a joy it has been to live; let us remember that basic poetry upon which existence really depends.

And in A Pagan’s Pilgrimage (1931), Powys himself wrote:

Out of gross beginnings tenderness has sprung up like snowdrops out of a wintry mould. Shame and suffering and horror there are, but there is also whispering in the wind. All is not lost. From the beginning to the end of life there is poetry.

Manuscripts and Book Collections relating to members of the Powys family at the University of Exeter

Llewelyn Powys: a Selection from his Writings at the Internet Archive

The object of Secularism is the promotion of human happiness in this world… [The Secularist] believes the surest way of […]

It is not to the point to say that the views of Lucretius and Bruno, of Darwin and Spencer, may […]

I don’t understand people panicking about death. It’s inevitable. I’m an atheist; you’d think it would make it worse, but […]

Kensal Green, opened in 1833, was London’s first commercial cemetery, and the originator of the city’s ‘Magnificent Seven’. These suburban […]