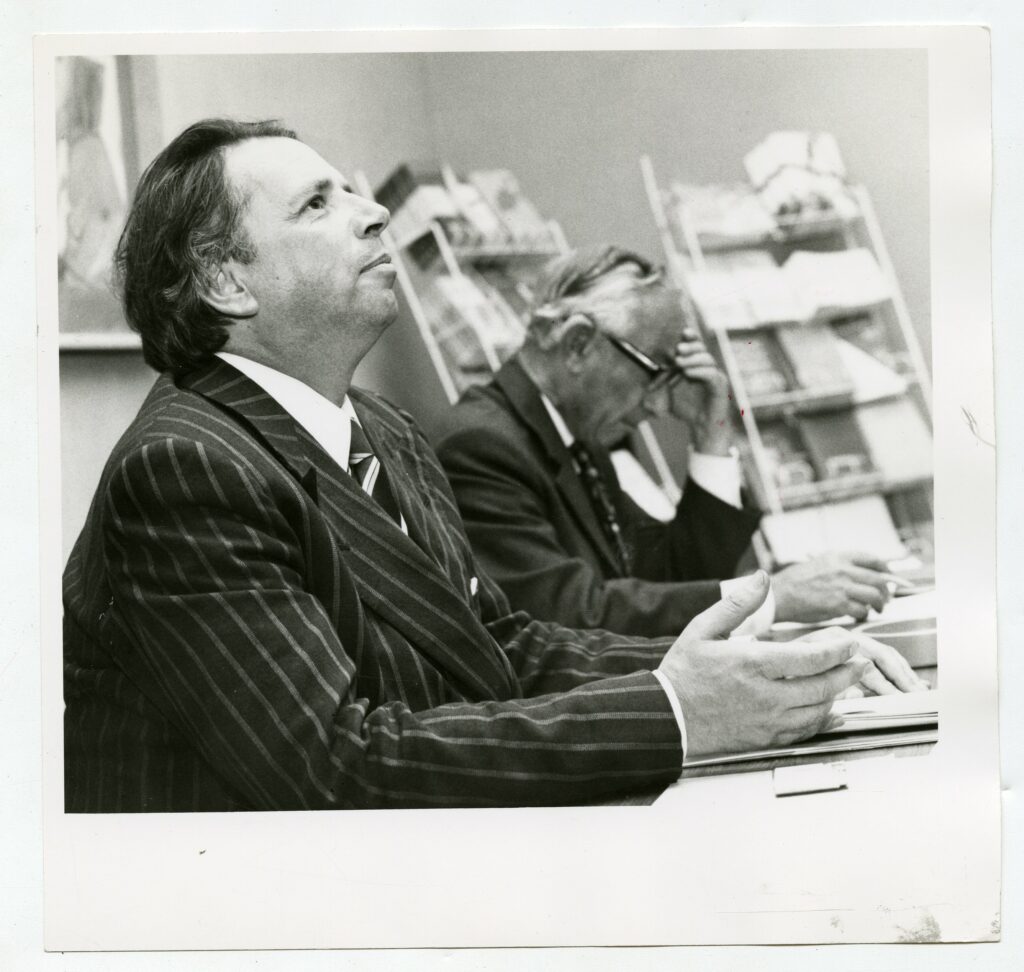

I don’t understand people panicking about death. It’s inevitable. I’m an atheist; you’d think it would make it worse, but it doesn’t. I’ve done quite a lot in the world, not necessarily of great significance, but I have done it.

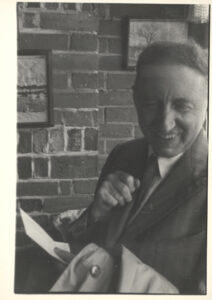

George Melly, 2005

George Melly was a jazz and blues singer, a writer and critic, and President of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) 1972-4. He lived an ebullient and unapologetic life, and, believing there to be just one, revelled in music, art, and relationships, embracing the joys he felt were all the sweeter without any notion of an encore.

Born in Liverpool in 1926, George Melly was introduced to the world of music and the arts from an early age by his Mother. As a boarder at Stowe School his passion continued to develop, and he soon acquired a keen interest in surrealism. His twin loves of surrealist art and jazz music would go on to dominate his life and shape his identity. After a brief stint in the Royal Navy towards the end of the Second World War, Melly found work at an art gallery in Soho owned by the Belgian surrealist E.L.T. Mesens. Melly thrived in this environment. He revelled in a bohemian lifestyle (perhaps a reason why his time in the Navy was always destined to be short-lived), and Soho, ‘a scruffy, warm, belching, argumentative, groping, spewing-up, cadging, toothbrush-in-pocket, warm-beer-gulping world’, was where Melly felt most at home.

It was during this time that Melly turned to performance, and he gained a popular following as the singer with Mick Mulligan’s Magnolia Jazz Band. Melly met his first wife at one of his Soho performances with the band, but the couple divorced in 1962 after they both had separate affairs with the same man. Later that year he met his second wife, Diana Dawson, and they married in May 1963, two days before the birth of their son, Tom. Throughout the 1960s he expanded on his popularity from his blues performances and became a prominent voice in the arts. He contributed to publications such as The Observer and the Daily Mail, writing film and music reviews amongst more detailed studies into the wider pop culture movement, such as his 1970 survey Revolt Into Style. He even turned his hand to scriptwriting, penning the films Smashing Time (1967) and Take A Girl Like You (1970). Melly returned to jazz in the 1970s, joining John Chilton’s Feetwarmers. Several successful albums followed, and Melly continued performing with the Feetwarmers, and latterly with Digby Fairweather’s band, well into old age. His exuberance and charm was fully unleashed and won him a place in many people’s hearts up and down the country.

Melly also published a number of memoirs, which recounted in warm yet outrageous fashion his upbringing in Liverpool, his time in the Navy and his jazz career. His infectious personality and love of humanity shines through these volumes. Melly spent his life as an atheist and found that this enhanced rather than diminished his experience of the world. He served as President of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) from 1972-74 and was a prominent member of both the National Secular Society and the Rationalist Association. He cared deeply about numerous social causes, once being arrested at a ‘Ban the Bomb’ march. As he himself said in 2002: ‘I still feel for the bullied and the oppressed and the victims of tyranny, and I still love my friends.’

Such empathy to his fellow man stemmed directly from his life-long commitment to humanist values, and even his declining health in his final years failed to dampen this position, nor blunt his wit and humour:

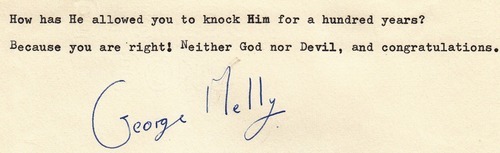

I remain completely faithful to humanism and will tell God so when I leave the building.

‘Coffee Break Interview’ with George Melly in the New Humanist, Spring 2002

Goodbye now.

‘Last Words’, The Guardian, 20 April 2006

George Melly’s irreverence belied a deep seated compassion for others, and a carefully reasoned and long-held humanism. Melly embraced the pleasures of life in comfortable certainty that it would end, inviting others through music and the written word to share those pleasures with him.

Living in a house beautifully situated on the outskirts of Coventry, they used to spend their lives in philosophical speculations, […]

About the moral problem there is nothing mysterious; it is simply the old, old question of how best to live […]

Humanism could (better) be honoured by reciting a list of the things one has enjoyed or found interesting, of the […]

Not Religion as a Duty, but Duty as a Religion. Felix Adler(A motto of the East London Ethical Society) The […]