The realisation of the possibility of a secular rational morality opens up a new perspective before the modern world… It must be realised that human existence is self-contained and self-sufficient; and that, therefore, man can find in himself the power to work out his destiny, to make a better world to live in.

M.N. Roy, Reason, Romanticism and Revolution

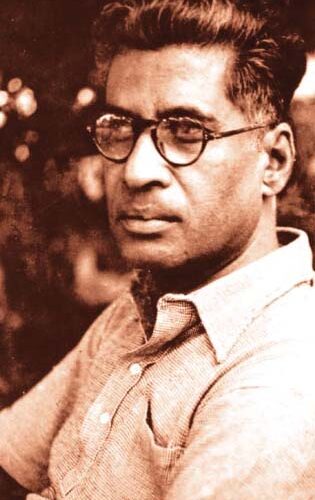

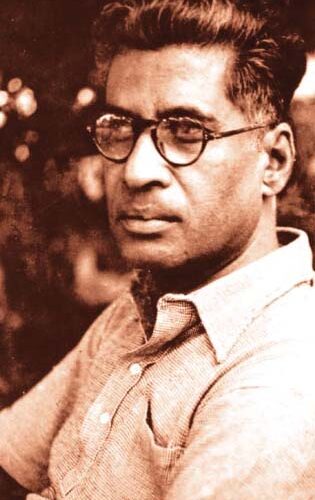

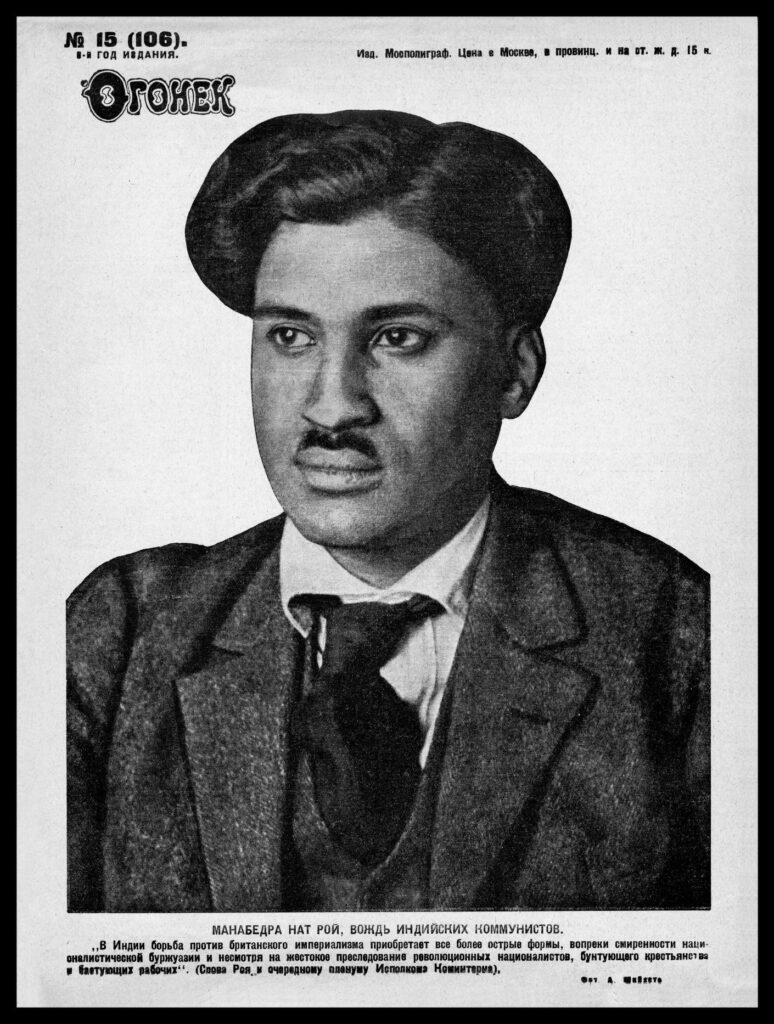

Manabendra Nath Roy was an Indian humanist and revolutionary, who created the Radical Humanist Movement in India. A founding member of the International Humanist and Ethical Union (now Humanists International), he was one of the IHEU’s first Vice Presidents. Roy was a staunch defender of democracy, and a lifelong advocate of reason and freedom. With his partner, Ellen Gottschalk Roy, he became a leading figure in Indian and international humanism, whose personal life and political activism were guided by a central devotion to truth, liberty, and human progress.

Freedom is the supreme value of life, because the urge for freedom is the essence of human existence.

M.N. Roy, Reason, Romanticism and Revolution

Roy was born on 21 March 1887 in a village near Calcutta, India, the son of a teacher. Educated locally, he soon became involved with anti-colonial struggles and revolutionary activity, most fervently from 1905 onwards. Roy left India in 1915, and spent time in California, where he associated with a range of American radicals and married his first wife, Evelyn. In 1917, he went to Mexico, where he became a leading figure in the Mexican Socialist Party. Converting to Marxism in 1919, Roy established the Communist Party of Mexico. Throughout the 1920s, he was actively involved in the international communist movement, until his expulsion from the Comintern over matters of principle in 1929.

In 1930, Roy returned to India, but was arrested within a few months of his arrival on charges of conspiracy to overthrow the state. He was sentenced to twelve years in jail, reduced to six on appeal. While imprisoned he read widely, and corresponded closely with German-Jewish writer and radical Ellen Gottschalk, who he had met in 1928. As well as providing him with books, Gottschalk organised a letter-writing campaign to demand Roy’s release, to which Jawaharlal Nehru and Fenner Brockway contributed.

Roy, who had separated from his first wife a decade earlier, married Ellen Gottschalk following his release in 1936. Settling in Dehradun, he continued to develop his theories of radical humanism, and became associated with Nehru and other progressives in Congress. Roy diverged from them with the onset of the Second World War, believing that – as fascism was the ultimate threat to freedom – India should support Britain in the war against Nazi Germany. He founded the Radical Democratic Party, which emphasised rationalism, cooperation, and human liberty, giving rise to New Humanism: a Manifesto. In 1946, after election defeat and an increasing disillusionment with the political system, Roy founded the Indian Renaissance Institute at Dehradun to promote the ideals of radical humanism. The RDP became, in 1948, the Radical Humanist Movement.

In that year, Roy began work on the major exposition of his scientific and humanist philosophy, the first volume of which was published in 1952 as Reason, Romanticism and Revolution. New Humanism, he wrote, reconciled ‘the romantic doctrine of revolution, that man makes history, with the rationalist notion of orderly social progress’. Its vision was based on the belief that:

Man is essentially a rational being. His nature is not to believe, but to question, to enquire and to know… New Humanism proclaims the sovereignty of man on the authority of modern science, which has dispelled all mystery about the essence of man. It maintains that a rational and moral society is possible because man, by nature, is rational and, therefore, can be moral, not under any compulsion, but voluntarily; that the sanction of morality is embedded in human nature.

New Humanism called for ‘a social reconstruction of the world as a commonwealth and fraternity of free men, by the cooperative endeavour of spiritually emancipated moral men’. For this, education would be central, and the pursuit of human freedom, and ‘common progress and prosperity’, the ultimate aims.

The first convention of the Radical Humanist Movement took place in Calcutta in February 1951. In 1952, Roy and the RHM were founding members of the International Humanist and Ethical Union, and Roy one of its first Vice Presidents. He died on 25 January 1954.

… the purpose of all rational human endeavour must be to strive for the removal of social conditions which restrict the unfolding of the potentialities of man. The success of this striving is the measure of freedom attained.

M.N. Roy, Reason, Romanticism and Revolution

M.N. Roy was an influential thinker and a tireless activist, who played a leading role in modern Indian freethought, and in growing the international humanist movement. A.B. Shah, founder of the Indian Secular Society and The Secularist journal, was significantly influenced by Roy’s ideas, stating that ‘Roy opened out new vistas of thought and intellectual freedom which gave positive content to my negative atheism’. In a commemorative seminar for Roy held in December 1987, Hermann Bondi – President of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) for nearly two decades – paid tribute to his remarkable capacity for change. Roy’s ‘transformation from the young rebel to the disciplined Marxist and then… the founder of Radical Humanism’ was, Bondi said, ‘an intensely human story’, and one which highlighted the distinctive adaptability of human beings, and of humanism. Learning from experience, for Roy and for Bondi, is a vital part of what makes us human.

With the Radical Humanist Movement, Roy sought to create a ‘complete system’, with human freedom and social improvement at its heart. In an appendix to New Humanism: a Manifesto, he laid out hopes for the movement which resonate clearly with the efforts of humanists today. The work of Radical Humanism, he wrote, would be judged:

…by the spread of the spirit of freedom, rationality and secular morality amongst the people, and in the increase of their influence on the State.

It is with a feeling of considerable deprecating delicacy that I venture to write of this woman, whom I so […]

‘Separate Development? Out of the closet, into the ghetto’ was a talk given by writer and activist Maureen Duffy on […]

Bessie Braddock was a trade union activist and politician, who devoted her life to improving the lives of others. She […]

Why not agree to differ about the questions which no one denies to be all but insoluble, and become allies […]