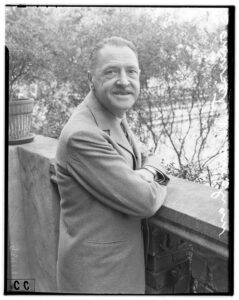

The international significance and reputation of Mohandas Gandhi is well-known, but his involvement with the burgeoning humanist movement during the early 20th century is much less remarked upon. Drawn to the Ethical movement by its unifying focus on moral action, Gandhi became a correspondent and close friend of Florence Winterbottom, and published a Gujarati translation of US ethical society leader William Salter’s Ethical Religion. While in London, Gandhi lectured at the Union of Ethical Societies’ Emerson Club, and his advocacy of the ultimate significance of ethical action – across races and religions – bore much in common with the Ethical movement.

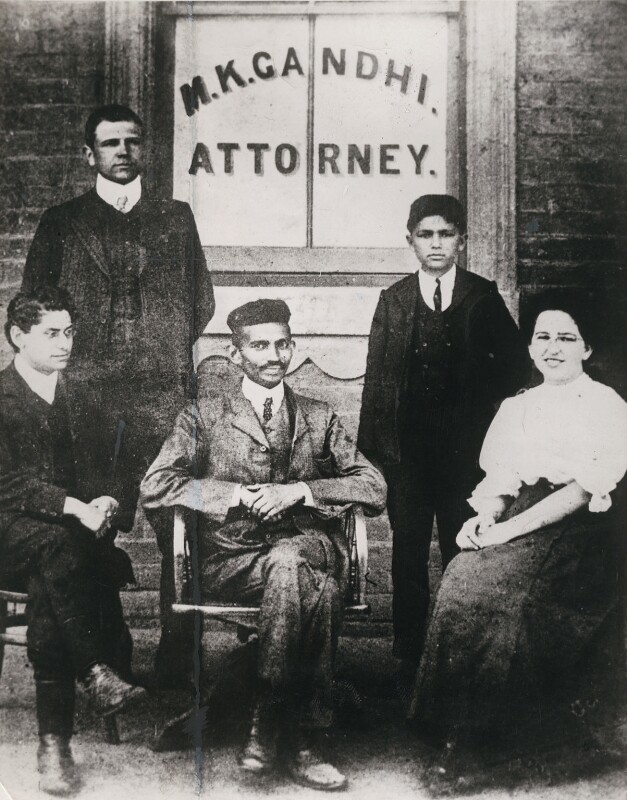

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born in Porbandar, western India in 1869. He studied law in London, and became a lawyer in South Africa. There, he became active in challenging racial discrimination, including leading a campaign against the requirement that Indians must carry identity cards. On his return to India, he was already a well-known figure, receiving the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal for Public Service in India in 1915. He went on to play an active role in the Indian nationalist movement, capturing the popular imagination and working for independence from British rule. Gandhi is best remembered today for his advocacy of non-violent resistance, or satyagraha (‘holding onto truth’), and his efforts to unify those of all classes and religions in its practise.

Like many leaders of the Ethical movement, Gandhi drew on a variety of religious and secular texts and teachings in developing his philosophy. His expansion of non-violence into a political philosophy drew on the ancient Indian ideal of ahimsa (non-injury, or doing no harm), which Gandhi described as ‘the first article of my faith’ and ‘the last article of my creed’. Though applied in the case of passive, but firm, resistance to oppression and injustice, non-violence was viewed by Gandhi as a philosophy which should permeate every aspect of life:

The very first step in nonviolence is that we cultivate in our daily life, as between ourselves, truthfulness, humility, tolerance, loving kindness.

Ahimsa extended to all sentient beings, and Gandhi became a committed vegetarian. He later credited humanist and animal rights advocate Henry S. Salt with convincing him of the moral necessity of vegetarianism. Salt’s A Plea for Vegetarianism was published in 1886. Both he and Gandhi were influenced by the ideas of Henry David Thoreau, of whom Salt wrote a biography, and who was also a notable influence on Ethical movement leaders including Moncure Conway, Felix Adler, and Stanton Coit.

Gandhi was inspired by the Ethical movement, and a reciprocal influence on various figures active within it. In 1907, Gandhi published a Gujarati translation of American Ethical society leader William Salter’s Ethical Religion (1889) in Indian Opinion. Introducing it, he wrote:

Mr. Salter, a learned American, has published a book on the subject, which is excellent. Though it does not deal with any religion as such, it contains teachings of universal application. We shall publish the substance of these teachings every week. All that needs to be said about the author is that he practices whatever he advises others to do. We would only appeal to the reader to try to live up to those moral precepts that appeal to him. Then only may we regard our efforts as having been fruitful.

A year earlier, Gandhi had met and become friends with Florence Winterbottom, Secretary of the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK), having made contact in the course of his first deputation to England on behalf of South African Indians. The two became close friends, and remained in regular correspondence until her death two decades later. Gandhi described Winterbottom as ‘among the rare men and women who find service its own reward,’ and acknowledged her unstinting – though not uncritical – support for him and his causes. Margaret Chatterjee has written that in the Union of Ethical Societies Gandhi appreciated ‘the company of a group which had no designs on his soul but with whom he found a lot in common.’ Another among these was Millie Polak, who had met her husband Henry Polak through the Ethical movement. Both became close friends and co-workers of Gandhi’s, spending many years with him in South Africa. Millie Polak wrote her recollections of Gandhi in Mr. Gandhi: The Man (1931), recalling her first impressions of him as a:

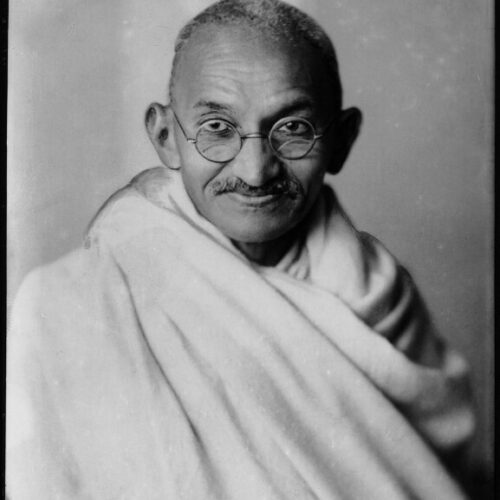

Medium-sized man, rather slenderly built, skin not very dark, mouth rather heavy lipped, a small dark moustache, and the kindest eyes in the world, that seemed to light up from within when he spoke. His eyes were always his most remarkable feature and were in reality the lamps of the soul; one could read so much from them. His voice was soft, rather musical, and almost boyishly fresh.

In 1909, on a second deputation to London, Gandhi again made contact with members of the Ethical movement, speaking at the Union of Ethical Societies’ Emerson Club, and attending Stanton Coit’s Ethical Church in Bayswater. A letter from Winterbottom written to Gandhi following the service included a membership card, which he had apparently requested, and an introduction to ethical society member James Ramsay MacDonald, soon to be visiting India.

When Gandhi returned to India in early 1915, his first years there were spent developing the Sabarmati ashram, and working to apply the principles of satyagraha to local issues. From 1919 onwards, he became actively involved in campaigning against British rule, leading three major satyagraha campaigns (1920-22, 1930-34, and 1940-42), for each of which he was imprisoned. The principles of satyagraha generated significant popular appeal, equipping the Indian people with an empowering means of resisting imperialism, without the threat of violent retaliation or societal breakdown. Although Gandhi ultimately felt that satyagraha had not been properly practised in India, and was deeply saddened by rising religious tensions and partition in the wake of independence, his influence on the popular imagination had been significant.

On 30 January 1948, Gandhi was assassinated in New Delhi by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu extremist. In line with his requests, he was cremated the following day.

…that glory that we saw for all these years, that man with divine fire, changed us also – and such as we are, we have been moulded by him during these years; and out of that divine fire many of us also took a small spark which strengthened and made us work to some extent on the lines that he fashioned.

Jawaharlal Nehru, Eulogy for Mahatma Gandhi (1948)

Gandhi’s central precepts of truth and non-violence, satya and ahimsa, underpinned his personal and political life, rooted in traditional Hindu thought, but universally applicable to ethical living. Gandhi’s concern was for the improvement of earthly conditions, and he emphasised the importance of a lived philosophy, rather than an isolated life of contemplation. Both had much in common with the activist idealism of the early humanist movement, as did his belief in the role of the individual in embodying moral values: bringing about radical change by devotion to their pursuit.

Some leading Indian freethinkers during Gandhi’s lifetime were involved with his efforts for home rule and non-violent protest, including M.N. Roy and Gora. Martin Luther King, Jr, deeply inspired by Gandhi’s commitment to non-violence, always carried a copy of The Gandhi Reader with him. Gandhi’s was a pluralistic view of religion, which he hoped would enable people of all faiths and none to live peacefully together – especially if a core ethical code could be shared among them. This echoed the ideals of the ethical societies, resonated in the later concept of the Open Society, and continues to animate the work of Humanists UK in dialogue today. Gandhi challenged oppression and discrimination, accepting imprisonment and risking physical harm in remaining true to his ideals. As Judith M. Brown has written:

He remains… a towering figure of the twentieth century… a symbol of anti-colonialism, and of the potential nobility of the human spirit.

The Progressive League was an organisation dedicated to the advancement of scientific humanism, founded by author H.G. Wells and philosopher […]

The good life… rests for its justification on no external authority, and on no system of supernatural rewards or punishments, […]

I remain an agnostic, and the practical outcome of agnosticism is that you act as though God did not exist. […]

Eliza Flower was a composer, a radical, and a significant influence on William Johnson Fox and the progressive values of […]