[I] feel extraordinarily proud and extraordinarily lucky to be the child of a woman who from her early twenties was an active and vigorous feminist, socialist and humanist.

Justin Keating on his mother, May Keating, in Nothing is Written in Stone: the Notebooks of Justin Keating (2017)

May Keating was a dedicated socialist, feminist, and human rights campaigner whose life embodied humanist principles of reason, compassion, and social justice. An agnostic from early adulthood, she actively opposed excessive clerical authority in Irish life and immersed herself in left-republican and feminist circles, working alongside figures like Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington. Her humanism fuelled a passionate anti-fascism, demonstrated through vigorous support for the Spanish Republican cause, membership of the Left Book Club, and activism against antisemitism and apartheid, alongside campaigning for nuclear disarmament and civil liberties. Keating fiercely advocated for women’s political and reproductive rights, personally assisting single mothers and championing the Mother and Child Scheme for free maternal care. Combining intellectual engagement, seen in co-founding the leftist journal The Plough, with practical action, she offered hospitality to radicals and dissidents. Remembered by the Irish Times for her blend of ‘robust common sense’ with ‘humanitarianism and idealism,’ and described directly by her son Justin as a ‘feminist, socialist and humanist,’ May Keating consistently translated her beliefs into sustained advocacy and action for a more just and humane society.

The biography reprinted below was first published in December 2017 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography. It is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International license.

Contributed by O’Riordan, Turlough

Keating, May (1895–1965), socialist, feminist and human rights campaigner, was born Mary Josephine Walsh on 6 October 1895, in Eadestown, Rathmore, Co. Kildare, to John Walsh, who farmed 70 acres there (28.3 hectares), and his wife Martha (née Cullen), a national school teacher. Her elder brother Joseph Walsh became a doctor, and married the novelist Una Troy. May (as she was generally known) was educated as a boarder by the Sacred Heart sisters in Roscrea, Co. Tipperary, until the combination of her mother’s death (1909), her father’s alcoholism, and her diagnosis of heart lesions due to rheumatic fever caused her to be sent to a sister house of the congregation near Seville, Spain. Completing her education there, she worked for a time as a bilingual secretary in Seville. Her engagement to a Viscayan engineer ended with his tragic death in a mining explosion in the Basque country, leading to her return to Ireland in May 1916. Living with a maternal aunt in Raheny, Dublin, that summer she joined the Keating branch (Craobh an Chéitinnigh) of the Gaelic League. The branch attracted political radicals, and it was there she met the artist Seán Keating.

May was briefly secretary to the republican Robert Barton and then to Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, whom she met while working with the Irish White Cross, raising funds for the dependants of republican prisoners… During the years that followed, she mixed in a left-republican and feminist milieu.

They married on 2 May 1919 in the University Church, St Stephen’s Green. By this time, May was an agnostic, and described herself as ‘independent’ on the marriage certificate. The couple lived in rooms in Rutland (Parnell) Square before moving in 1921 to a small rented cottage at the edge of the Featherbeds, Killakee, Co. Dublin. Having trained as a typist at Caffrey’s Secretarial College, Dublin, May was briefly secretary to the republican Robert Barton and then to Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, whom she met while working with the Irish White Cross (1920–22), raising funds for the dependants of republican prisoners. In 1922 she spent two months teaching at the Berlitz school in Hamburg, and returned to Dublin that autumn. During the years that followed, she mixed in a left-republican and feminist milieu that included Rosamond Jacob, Charlotte Despard, Dorothy Macardle, Harry Kernoff and Sheehy-Skeffington. Keating was active in Friends of Soviet Russia.

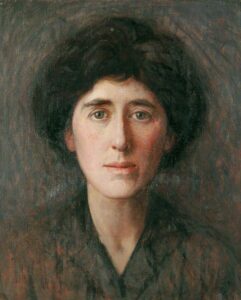

Seán Keating used May as a model in many of his paintings… His biographer argues that he consistently portrayed her as a ‘woman of character; her gaze, which is never direct, is always suggestive of a lively intellect’.

Seán Keating used May as a model in many of his paintings. In ‘An allegory’ (1924), she represents Mother Ireland feeding an infant, offering some hope for Ireland’s future in a painting representing Seán’s despair at the Irish civil war and despondency at Ireland’s innate conservatism. In ‘Night candles are burnt out’ (1929), she is shown as a wife and mother optimistically viewing the construction of the Ardnacrusha hydroelectric power station on the river Shannon. Although she requested that Seán should not depict her political activism in his paintings, she certainly influenced his political sensibilities, and their unity in supporting socialist and republican causes was clearly evident. His biographer argues that he consistently portrayed her as a ‘woman of character; her gaze, which is never direct, is always suggestive of a lively intellect’ (O’Connor, 84).

Her enthusiastic membership of Victor Gollancz’s Left Book Club – the Dublin branch was founded in October 1936 and led by Sheehy-Skeffington – spurred May’s left-wing activism and militant anti-fascism.

The couple had two sons, Michael (1927–2001) and Justin. In 1935 they moved to ‘Áit an Chuain’, in Willbrook, Ballyboden, Rathfarnham, Co. Dublin, enabling the two boys to attend the local primary school. May busied herself with her garden and caring for animals, often adopting strays. She retained a deep affection for Spain and, disenchanted with Roman catholicism religiously and politically, passionately supported the republican side in the Spanish civil war (1936–9). Her enthusiastic membership of Victor Gollancz’s Left Book Club – the Dublin branch was founded in October 1936 and led by Sheehy-Skeffington – spurred May’s left-wing activism and militant anti-fascism. Her son Justin later recalled her saying: ‘I know from personal experience that to describe Franco as an upright, Christian gentleman is three lies in three words’ (Hussey and Kealy, 19). She hosted Fr Ramon Laborda, a pro-republican Basque priest who visited Ireland in 1937, and acted as his interpreter when he spoke of Spanish nationalist atrocities at public meetings in Dublin organised by the Spanish Aid Committee. The committee, which included other militant women, such as Sheehy-Skeffington, Macardle and Nora O’Connolly O’Brien, raised money and helped organise medical support for republican forces in Spain.

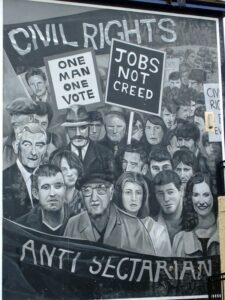

May Keating passionately advocated for women’s political and reproductive rights, defending the right of single mothers to raise their own children, and helping many of them personally. She strongly denounced excessive clerical authority in Irish social and political life. Her participation in the ‘mother-and-child scheme committee’ (1951) brought her activities into the public glare, as she campaigned strongly for the free maternal and infant medical services then being proposed by Minister for Health Noel Browne. During 1952 she and Browne considered founding a new, left-wing, non-communist political party, after William Norton had blocked Browne’s joining the Labour party. Throughout the 1950s, the Keatings welcomed radicals, dissidents and activists to their open house, and often housed and fed them along with a circle of struggling artists and poets. They regularly attended the Sunday salons hosted by Austin Clarke in Templeogue, and were active in numerous causes, denouncing anti-Semitism in Ireland and abroad, and supporting the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement in the 1960s. May was a prominent member of the executive committee of the Irish Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and was a member of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties.

May Keating passionately advocated for women’s political and reproductive rights, defending the right of single mothers to raise their own children, and helping many of them personally. She strongly denounced excessive clerical authority in Irish social and political life.

In the mid 1950s, Keating was a leading figure in the electoral organisations of Browne and his fellow left-winger Noel Hartnett. After Browne stood unsuccessfully in Dublin South East for Fianna Fáil in 1954, Keating helped secure his election as an independent in 1957. In October 1956 she attended a meeting convened by trade unionist Matt Merrigan to discuss forming a new political party, at which Browne (then still on Fianna Fáil’s national executive) and Jack McQuillan urged the establishment of a new, outspoken, left-wing publication. Along with James Plunkett and Owen Sheehy-Skeffington, Keating was one of the founders of the Plough (1957–68), a cooperatively owned and managed monthly journal, which addressed social, educational and political issues from a leftist view. Keating contributed several articles, and also raised subscriptions, assisted editorially, and organised printing and distribution to sympathetic newsagents.

Justin’s description of May as a vigorous ‘feminist, socialist and humanist’ captures the range of her sustained and committed advocacy… The Irish Times noted that she ‘combined robust common sense and a blessedly unsentimental attitude with humanitarianism and idealism’.

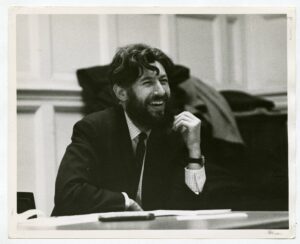

Keating was active in the 1913 Club, a political discussion group founded in 1957 by Owen Dudley Edwards, David Thornley and others, which espoused the socialist nationalism of James Connolly and the democratic programme of the first dáil. Thornley later described Keating as one of the two greatest influences on his life (Ir. Times, 8 May 1976). The 1913 Club clashed in July 1958 with Browne’s and McQuillan’s new party, the National Progressive Democrats. Browne’s fear of communist infiltration of his electoral organisation, whose membership overlapped with supporters of the Plough, led him to denounce Justin Keating, then being considered for the journal’s editorship, as an avowed communist (Ir. Times, 2 May 1957). Browne also took the opportunity to distance himself sharply from May, whose independent outlook and apparent communist sympathies increasingly troubled him. Matt Merrigan though, thought her a republican socialist, interested in Marxism and Soviet Russia, but not a communist. Justin’s description of May as a vigorous ‘feminist, socialist and humanist’ (Hussey and Kealy, 83) captures the range of her sustained and committed advocacy.

May Keating died of heart failure on 4 March 1965 at ‘The Wood’, Ballyboden Road, Rathfarnham, Co. Dublin, and was buried at Cruagh cemetery, Rockbrook, Co. Dublin. The Irish Times noted that she ‘combined robust common sense and a blessedly unsentimental attitude with humanitarianism and idealism’ (11 March 1965).

GRO (subject’s birth, death certs.; parents’ marriage cert.; mother’s death cert.); Ir. Times, 23 May 1951; 11 Mar. (appreciation, as ‘Mrs John Keating’), 23 June 1965; 12 Apr. 1969; 8 May 1976; Noel Browne, Against the tide (1986) passim; Andrée Sheehy-Skeffington, Skeff: the life of Owen Sheehy Skeffington (1991), 262; John Horgan, Noel Browne: passionate outsider (2000); Roy H. W. Johnston, Century of endeavour: a biographical and autobiographical view of the twentieth century in Ireland (2003); Dermot Bolger (ed.), County lines: a portrait of life in South Dublin County (2006), 138; Niamh Puirséil, The Irish Labour Party 1922–73 (2007); Éimear O’Connor, Seán Keating: art, politics and building the Irish nation (2013), passim; Matt Merrigan, Eggs and rashers: Irish socialist memories (2014), ed. D. R. O’Connor Lysaght; Barbara Hussey and Anna Kealy (ed.), Nothing is written in stone: the notebooks of Justin Keating (2017); private information

Main image: Section of ‘Night’s Candles Are Burnt Out‘ by Sean Keating, modelled on May Keating

A brief history of humanism and secularism in Northern Ireland Organised humanism began in Northern Ireland in the 19th century, […]

When we stand up for freedom of conscience, for the rights of the individual, for the rational approach and against […]

Thomas Hill Green was a philosopher, educator, and a Liberal, whose idealist philosophy (with its practical implications) was a significant […]

For many years a member of the Rationalist Press Association, and no longer associated with any church, she had devoted […]