Good will, that curious product of consciousness, of leisure and energy to spare and share. That thing we put out against the forces of interest… a thing we can have too much of for our own immediate surroundings and belongings, as a mother can have too much milk for her baby. We have to give it away, not only in place but in time. We have to give even to the future.

Naomi Mitchison, We Have Been Warned (1935)

By Nicolas Walter, originally published in New Humanist, March 1999

Naomi Mitchison may be seen as an exemplary representative of the century she lived through. She played many parts but the whole was greater than the sum of the parts. She was a very human person in every sense, who filled each moment of her very long life to the brim, who gave love and friendship to her large family and her larger circle of friends who reached an even larger public with a stream of publications of all kinds and who never stopped trying in every way she could to make the world a better place.

She was a very human person in every sense… who never stopped trying in every way she could to make the world a better place.

Naomi Mary Margaret Haldane came from a remarkable Scottish family. Her uncle was R. B. Haldane (Lord Haldane of Cloan), the Liberal and then Labour Lord Chancellor; her father was the physiologist and philosopher J. S. Haldane; her mother was the formidable hostess Kathleen Trotter; her brother (her first and greatest love) was the pioneering geneticist J. B. S. Haldane. She was born in Edinburgh on 1 November 1897 but grew up in Oxford where her father was a fellow of New College. She was educated at the Oxford Preparatory School (later the Dragon School), at home, and then at the Society of Oxford Home-Students (later St Anne’s College). She showed much promise in biology, but was never able to obtain any qualifications or practise any profession, though she studied widely and was particularly impressed by the work of James Frazer and C. G. Jung. She was brought up in a privileged but restricted background, and had difficulty freeing herself from dependence on her parents and from the conventions of her class.

But for her, as for so many others, everything was changed by the First World War, which destroyed the world she knew. In 1915 she worked as a nurse at St Thomas’s Hospital in London and the John Radcliffe infirmary in Oxford, and in 1916 she married her brother’s friend Gilbert Richard (Dick) Mitchison, a lawyer five years older than herself who was serving in the army in France. He was severely wounded in action, but she nursed him back to health: he began his career and she began a family. After the war they lived in London, where he worked as a barrister and she worked as a mother but also as a writer, and they formed the nucleus of a largely left-wing intellectual circle.

She was an active supporter of birth control — helping to run the North Kensington Clinic and speaking and writing on the subject.

She was an active supporter of birth control — helping to run the North Kensington Clinic and speaking and writing on the subject — but joyfully if painfully had seven children over 22 years. She suffered bitter loss: her first son died from meningitis (cruelly described in Aldous Huxley’s Point Counter Point), and her last daughter died soon after birth (gently described in her memoirs). She also enjoyed sweet success: her other three sons became distinguished scientists and Fellows of the Royal Society – one introduced her to James Watson, and she helped to edit The Double Helix, which was dedicated to her — and her other two daughters became writers. She later had many grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and gave her recreation as ‘keeping up with the family’ (later replaced by ‘surviving so far’). Her marriage was happy, but not entirely satisfactory, despite help from the books of Marie Stopes, and both she and her husband entered several other relationships, which were conducted with dignity and described with humour. As the Second World War approached they moved to Carradale House in Kintyre, which became her base for the rest of her life, and where she farmed her land, entertained her guests, and took an active part in local and regional affairs.

She was a radical in both religion and politics. Her parents were agnostics, and she went further… supported the freethought movement, joined the Rationalist Press Association, and served as a director of the short-lived paper of ‘scientific humanism’, The Realist (1929).

She was a radical in both religion and politics. Her parents were agnostics, and she went further (if not as far as her brother’s militant atheism), supported the freethought movement, joined the Rationalist Press Association, and served as a director of the short-lived paper of ‘scientific humanism’, The Realist (1929). Her mother was a Conservative and her father a Liberal, and she began as the former but moved through the latter to Socialism (if not as far as her brother’s militant Communism). She supported the League of Nations Union, and eventually joined the Labour Party and the Fabian Society. She was involved in the work of Tom Harrisson’s Mass-Observation from its start in 1937. She supported the Popular Front but was never a Fellow-Traveller with the Soviet Union, which she visited in 1934, and she sometimes insisted that she was really a liberal or even an anarchist. She stood unsuccessfully for the Scottish Universities seat in 1935, and served on the Argyll County Council on and off from 1945 to 1965. She proved a loyal supporter of her husband as a Labour candidate from 1931, Member of Parliament from 1945, and Life Peer from 1964 until his death in 1970 (though she characteristically refused to be called Lady Mitchison). She also supported the Scottish Nationalists, became vice-chairman of the non-party Scottish Convention, and served on the Highland and Island Advisory Panel and then on the Highlands and Islands Development Consultative Council from 1947 to 1976.

She supported the Authors’ World Peace Appeal in the 1950s, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the 1960s, and then the Greenham Common women in the 1980s — earning local unpopularity for her opposition to the nuclear submarine base in the Holy Loch, not far from her home.

She accepted the need for fighting in the two World Wars and the Spanish Civil War, though she hated what it entailed, but she objected to the reliance on nuclear weapons in the Cold War, and she supported the Authors’ World Peace Appeal in the 1950s, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the 1960s, and then the Greenham Common women in the 1980s — earning local unpopularity for her opposition to the nuclear submarine base in the Holy Loch, not far from her home.

Later in life she became unexpectedly involved in Southern Africa. In 1963 she was invited by her friend Linchwe, who had become the chief of the Bakgatla tribe in Bechuanaland (later Botswana), to become his adoptive mother. She accepted the position of Tribal Mother with enthusiasm, putting into practice what she had written about in theory and continued to visit her tribe into her nineties.

* * *

Naomi Mitchison was above all a feminist — though she often repudiated the term — who fought hard in private and then in public for the right of herself and other women to take a full part in all aspects of both private and public life.

BUT Naomi Mitchison was best known as a prolific and popular writer. During a career of seventy years she contributed thousands of articles and Ietters to scores of papers, and produced books at a rate of more than one a year. She made her name with historical novels. The Conquered (1923), about the Roman conquest of Gaul, brought her appointment as Officier de I’ Académie Francaise; The Corn King and The Spring Queen (1931), an ambitious treatment of cultural and sexual conflict in ancient Greece and Scythia, earned admiration from both critics and readers; and The Bull Calves (1947) drew on her Scottish roots. She wrote poetry and drama, but was discouraged by the reaction of other poets and dramatists. She wrote biographies. She wrote modern fiction — We Have Been Warned (1935), which was censored by her publishers and censured by the reviewers for its sexual and political frankness, stands as what she called a ‘historical novel about my own times’. She edited factual symposia — An Outline for Boys and Girls and Their Parents (1932) became a secular bible for many progressive families, though What the Human Race is Up To (1962) was less successful. She wrote children’s books and science fiction — Travel Light (1952) and Memoirs of a Spacewoman (1962) became classics. She wrote books about Scotland which contributed to the Scottish Literary Renaissance, and books about Africa which were banned by the South African government. She wrote practical philosophy – The Moral Basis of Politics (1938) and the Haldane Memorial lecture on Sittlichkeit (1975) were straightforward expositions of the decent life. She produced a series of books based on her diaries and letters, both documentary records — Vienna Diary (1934), Mucking Around (1980), Among You Taking Notes (1985) — and more impressionistic memoirs — Small Talk (1973), All Change Here (1975), You May Well Ask (1975) – which together provide a remarkable account of her era. She was an active member of PEN and President of the Saltire Society.

Naomi Mitchison was above all a feminist — though she often repudiated the term — who fought hard in private and then in public for the right of herself and other women to take a full part in all aspects of both private and public life. Her literary work was saturated with feminist considerations, though she never finished The Intelligent Women’s Guide Through Feminism which she began in the 1930s. She was recognised by the later women’s movement as one of its heroines — several of her books were reprinted by feminist publishers — and this is probably how she will be remembered. Many of her papers went to the Humanities Research Center in Austin, Texas, and the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh; before she died there were already academic dissertations on her work and also two biographies — by the American writer Jill Benton, Naomi Mitchison: A Century of Experiment in Life and Letters (1990), and by the British writer Jenni Calder, The Nine Lives of Naomi Mitchison (1997); and as she approached death she was the subject of several profiles and interviews.

But before she falls into the lifeless hands of posterity, she should be remembered for her wonderfully living presence and her shamelessly contradictory character.

But before she falls into the lifeless hands of posterity, she should be remembered for her wonderfully living presence and her shamelessly contradictory character. She was a Victorian who welcomed the modern age but was alarmed by it, an extravert who exposed her weaknesses as well as her strengths to an often hostile public, a rationalist who suffered from nightmares and panics, wept as much as she laughed, and started physical as well as verbal fights, a humanist who sympathised with religion and ritual, a radical who refused the OBE but accepted the CBE, a reformer who always stressed ‘what people really want’ and tried to speak for ‘the people who have not spoken yet’, a moralist who insisted on the necessity of decency but never forgot the need for fun, a combination of bohemian intellectual, ancient witch and grande dame, a patrician with the ringing voice of her class who mixed with ordinary people in all parts of the world and struggled for a new world in which all people should have the chance of a good life. She wrote near the end of her own good life, ‘But the bright vision fades, always, always’; though she added, ‘We wait for a new wave of hope.’ Her vision never faded: she never lost hope. She adopted the motto ‘Adventure to the Adventurous’, and followed it to the end.

She celebrated her hundredth birthday at home with several hundred guests, and looked forward to death as yet another interesting adventure. She seemed immortal, but she finally died at her home at the age of 101 on 11 January, 1999, leaving five children, dozens of other descendants, and countless acquaintances and admirers.

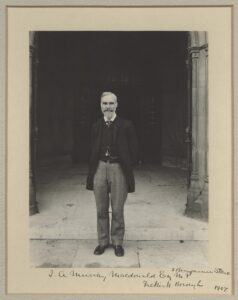

Main image: Naomi (Lady) Mitchison, 1897-1999 by Clifton Pugh © Dailan Pugh and Shane Pugh. National Galleries of Scotland

The Ruskin School Home was founded by socialist writer and teacher [Harry] Bellerby Lowerison (1863–1935) in Norfolk in 1900, following […]

Humanism is a philosophy – one which gives us a coherent stance for living. We believe the humanist approach to […]

The London Ethical Society was the UK’s first, founded in 1886 to pursue ‘a rational conception of human good’: establishing […]

…the only efficient, the only decent prayer, is Action. John Galsworthy, ‘Philosophy of Life’ in Glimpses and Reflections (1937) Best […]