What is needed is something in which [we] can all believe irrespective of religion, which in most cases, dare I say it, is a facade. We need something else, and that something is ethics. Goodness, kindness, love, honesty.

Nicholas Winton in an interview with The Guardian, 2014

Nicholas Winton was a stockbroker, humanitarian, and humanist, who saved the lives of more than 650 Jewish children ahead of the Second World War. A modest man, whose life-saving efforts were unknown to those close to him until half a century later, he was motivated by a profound sense of collective responsibility and an instinctive drive to do what he could. Winton was made an MBE for his charitable work five years before his pre-war efforts had been discovered, having formed the Abbeyfield Maidenhead Society to provide care homes for the elderly, as well as establishing the Maidenhead branch of Mencap. He was a member of Humanists UK, and always frank about his own non-religion, advocating instead for unifying ethical values which could be shared by everyone.

If you call that charity work which I suppose it was I’ve always done charity work… It’s just work I like doing. You don’t need any particular gift. I don’t know what urges one on to do it at all.

Interview with Nicholas Winton, 17 November 1995, United States Holocaust Museum

Nicholas Winton was born Nicholas Wertheim in West Hampstead on 19 May 1909 to parents of German-Jewish descent. He was educated at Stowe School, Buckinghamshire, leaving in 1926 and pursuing a career in banking. Following his father’s death in 1937, Nicholas’ mother changed the family name to Winton.

During his early career Winton worked in various European cities, during which time he became fluent in German and French. Back in England, he became active in left-wing circles and a member of the Labour Party. A turning point in his own activism came during a 1938 trip to Prague, taken at the invitation of a friend, where he witnessed the plight of Jewish refugees from the Sudetenland — then already under Nazi occupation. In Prague, he met Doreen Warriner, who ran the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia. Winton recalled:

…in conversation she said, “There are all these children, you know, who should be got out, but the British Committee just can’t do anything about it at all. They’re far too overworked with the business of trying to get out the political refugees, the writers and all those people endangered,” and said to me, “Look, if anything can be done, perhaps you’d like to try and do it,” and that’s really how it started.

Interview with Nicholas Winton, 17 November 1995, United States Holocaust Museum

At Warriner’s suggestion, Winton set about drawing up lists of names for consideration, writing home to his mother from Prague with a view to finding out what could be done. When, on 16 November 1938, the government agreed to permit the entry of unaccompanied children up to the age of 17, the scheme which would become known as the Kindertransport was born.

Winton returned to London in January 1939, and worked tirelessly alongside his job to lobby and appeal for the required hosts and guarantees for these refugee children. Between March and September that year — when the outbreak of war called a halt to the Kindertransport — eight trains brought 669 young people from Prague to London. The families of most of these would be murdered during the Holocaust. A self-described agnostic, Winton said:

There was no question when we were looking for a family to look after the children that a Jew should go to a Jew or a non-Jew should go — it seemed to us at that time perhaps because I’m non-religious myself I don’t know but it seemed to me completely secondary. The chief thing was to save the children.

Interview with Nicholas Winton, 17 November 1995, United States Holocaust Museum

During the war itself, Winton, a conscientious objector, served as an ambulance driver in France before joining the RAF. At the war’s end, he joined the International Refugee Organization, managing efforts to repatriate looted Jewish property. He subsequently worked for the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Winton married Grete Gjelstrup, who he’d met while working in Paris, in 1948. They settled in Maidenhead, and had three children. He continued his work in finance, as well as maintaining his political and charitable interests, and staying active in the Labour Party. His own son having had Down’s Syndrome, and dying aged just seven, Winton established the Maidenhead branch of Mencap, devoted to supporting learning disabled people and their families. He was also responsible for founding the Abbeyfield Maidenhead Society, providing sheltered housing and residential care homes. Today, two of these, Winton House and Nicholas House, bear his name. For these efforts, Winton was made an MBE in 1983.

It was not until five years later, following the discovery by his wife of a scrapbook in the attic, that Winton’s humanitarian efforts 50 years earlier came to be recognised. This led to a story in the Sunday Mirror, and a moving episode of Esther Rantzen’s That’s Life, reuniting Winton with many of those he saved, and propelling him into the public eye. He was the subject of a biography and documentary, was knighted in 2003, and nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009. Nevertheless, Winton was always quick to challenge the idea of him as a lone hero, highlighting the efforts of those who had worked alongside him – often at significant personal risk. He described his own contribution, by comparison, as ‘modest’. Winton died in Berkshire in 2015, aged 106.

This is a beautiful story — it radiates with inspiration and proves that much good can still be done on this earth.

Vaclav Havel in a tribute to Nicholas Winton, 1998, in Nicholas Winton and the Rescued Generation by Muriel Emanuel and Vera Gissing (2002)

Nicholas Winton’s efforts, and those of his colleagues, ensured the safety of hundreds of children, among them the humanist politician Alf Dubs. His example is a reminder of the profound impact a single individual can have, as well as of the transformative power of collaboration and compassion, even in the face of humanity’s worst atrocities.

Winton [formerly Wertheim], Sir Nicholas George by Caroline Sharples | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Interview with Nicholas Winton | United States Holocaust Museum

Sir Nicholas Winton obituary | The Guardian

Sir Nicholas Winton | Holocaust Memorial Day Trust

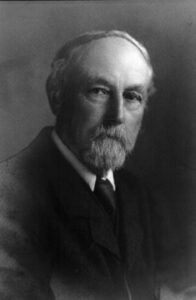

Main image: Nicholas Winton in 1938 by the Associated Press.

Girton College at the University of Cambridge has educated and employed a host of remarkable humanists and freethinkers, many of […]

The obituary reproduced below was written by George Broadhead, and originally appeared in a 1997 issue of The Gay Humanist […]

We have the faculties for gaining knowledge; and Rationalism will always maintain that we are at liberty to use them […]

The Humanitarian League is a Society of thinkers and workers, irrespective of class or creed, who have united for the […]