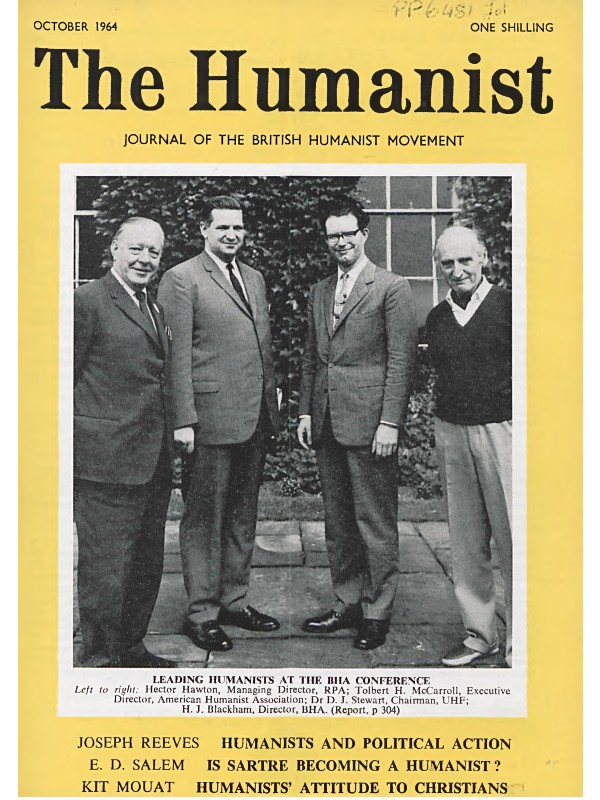

From the early 1960s, with other members of the burgeoning British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK), H.J. Blackham pioneered a humanist counselling service – a direct forerunner of today’s Non-Religious Pastoral Support Network. Blackham and his colleagues felt that the initiation of ‘pastoral humanism’ was key to the development of the humanist movement, and a distinctive offer they might make to the wider community. Humanists in America, and elsewhere in Europe, were already experimenting with the offer of counselling, and these letters between Blackham and his counterpart in the American Humanist Association, Tolbert McCarroll, were part of an ongoing correspondence about the service. Along with these letters, held in the archives of the British Humanist Association at the Bishopsgate Institute, is a document titled ‘The Humanist Concern for Counselling’, which reads in part:

The message of Humanism has [at] its core, an appeal to human possibilities and human solidarity, and does not pride itself therefore on any kind of perfection, but is geared upon a humaneness with all the shortcomings and brokenness which cannot be sidestepped…

In his letter, Blackham expressed gratitude for materials provided by McCarroll concerning the AHA’s counselling programme, and stated his conviction that: ‘this service if properly developed could be one of the most important undertakings of an organised Humanist movement’.