As well as being home to Conway Hall and its humanist library, Red Lion Square contains statues of two prominent humanists and pacifists: Fenner Brockway and Bertrand Russell.

A lifelong socialist, anti-racist, and peace campaigner, Fenner Brockway (1888-1988) founded the No Conscription Fellowship in 1914 (at the suggestion of his wife, Lilla) to resist compulsory military service. Alongside Bertrand Russell he was a founding member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in 1957 and, aged nearly 90, co-founder of the World Disarmament Campaign in 1979. He was a member of the Advisory Council of Humanists UK. Behind all of this lay a love of, and loyalty to, his fellow human beings:

My loyalties were not to a country, but to the dispossessed of all countries who were denied real life in peace and summoned to die in war for the very system of which they were the victims.

Fenner Brockway

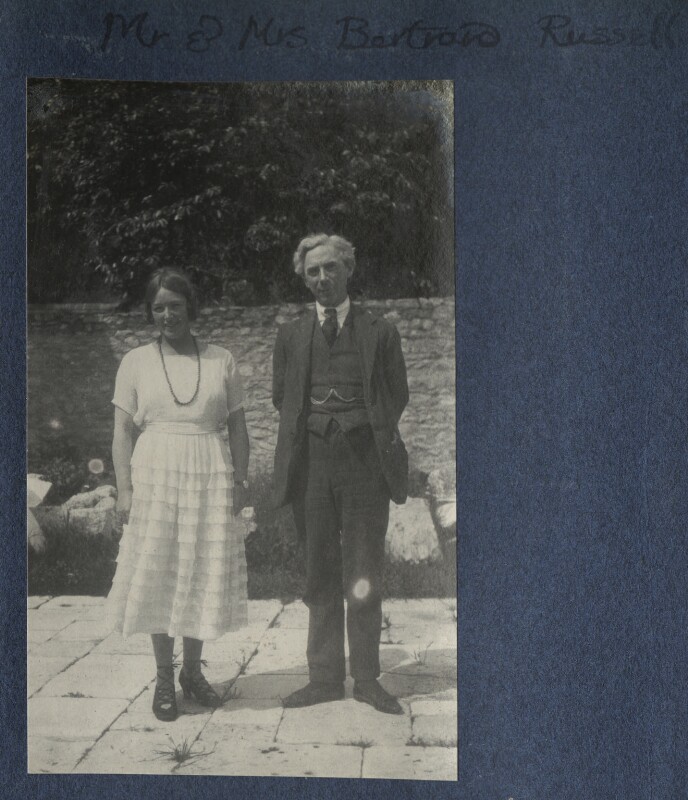

Brockway’s CND co-founder Bertrand Russell (1872-1970), a philosopher and activist, was also a lifelong champion of humankind. In What I Believe (1925), Russell laid out a humanist manifesto for living. ‘The good life,’ he said, ‘is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge.’

To live a good life in the fullest sense a man must have a good education, friends, love, children (if he desires them), a sufficient income to keep him from want and grave anxiety, good health, and work which is not uninteresting. All these things, in varying degrees, depend upon the community, and are helped or hindered by political events. The good life must be lived in a good society, and is not fully possible otherwise.

This concept of ‘the good life’ and the creation of a world that could best enable it was ever present in the principles of the early ethical societies, which later became Humanists UK. Russell was a member of the Advisory Council for Humanists UK for many years, and President of Cardiff Humanists until his death.

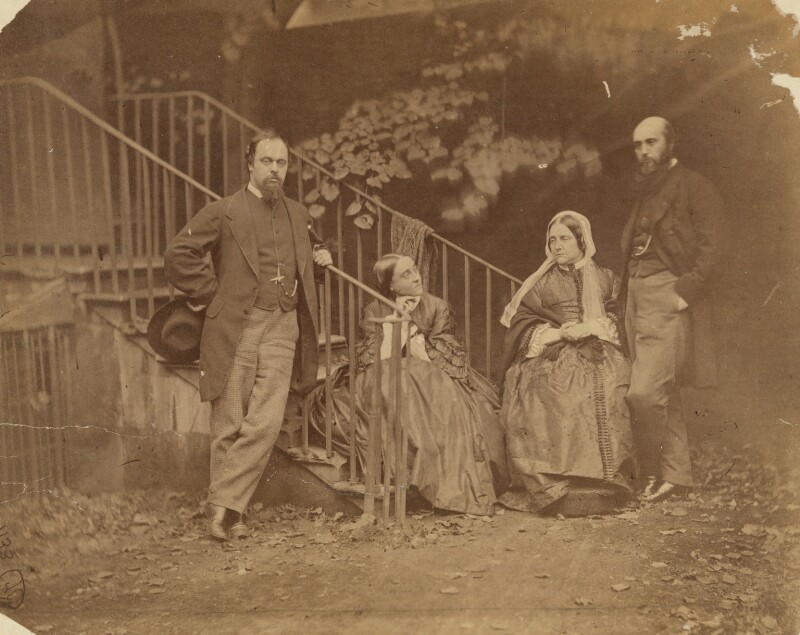

A plaque at number 17 marks a house in which freethinkers Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Morris lived. Poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) was described by ethical society member Ernestine Mills as ‘full blooded, impetuous, Agnostic’. Rossetti’s brother William was also forthright about his own agnosticism:

The term “Agnostic” was not invented in those years. As soon as it got invented, I found it to be the clearest and the simplest definition of my mental position in relation to the supernatural – a position which amounts to this; that a number of things are affirmed by many people concerning matters beyond their observation, and beyond mine; and that, as I know nothing about those things, and am not conscious that anything can be known about them, I likewise profess to know nothing.

The term agnostic (from Greek agnōstos, ‘unknowable’) was coined by T.H. Huxley in 1869 at a meeting of the Metaphysical Society. A word for the concept that we cannot know anything for certain beyond the physical world of our experience was, he said, an answer to those theologians ‘who professed to know so much about the very things of which I was ignorant’.

Designer, poet, and publisher William Morris (1834-1896) was a socialist and freethinker, with a ‘grand and sympathetic view of human potential’. His vision was one of social improvement on earth, and human collaboration as the means to happiness:

Fellowship is heaven, and lack of fellowship is hell.

William Morris

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Red Lion Square was undoubtedly London and the UK’s most prominent hub of humanist and secular activism, home not only to the Conway Hall Ethical Society, but also to the National Secular Society, the British Humanist Association (today’s Humanists UK), and several of the smaller groups. In the early 2000s, Humanists UK moved to Gower Street, to enjoy a decade-long stay as neighbours to UCL, together the ‘Godless of Gower Street’.

About the moral problem there is nothing mysterious; it is simply the old, old question of how best to live […]

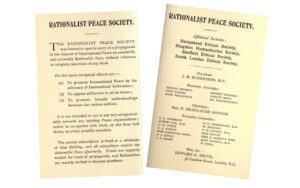

…a slowly growing public opinion in favour of arbitration as the alternative to war… is not in consequence of any […]

I have come to feel that the best proof of the subjection and degradation of my sex lies in the […]

Its aim will be to secularise education and make moral training the chief aim of the school life. A great […]