But this much is certain, that, taking the world as we find it, sympathy, plus a modicum of common sense – in other words, sentiment directed by reason – would appear to be the most practical remedy for human afflictions.

Spirit, Matter and Morals, 1908

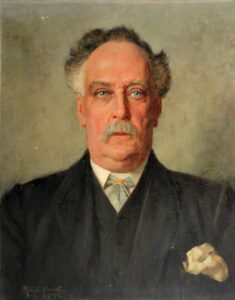

Richard Dimsdale Stocker was an author, lecturer, and significant figure in the 20th century Ethical movement. Little remembered today, Stocker was a prolific and wide-ranging writer, as well as the founder of the Brighton Ethical Society, president of the Hampstead Ethical Institute, and editor of the Ethical Societies’ Chronicle. A prolific writer with a diverse range of interests, Stocker is an intriguing example of the kind of individual drawn to the burgeoning humanist movement in its early years, and of one whose active devotion helped enlarge and promote it.

Richard Dimsdale Stocker was born on 10 May 1877, the son of a physician. His parents were religious – his mother’s family members of the High Anglican Church, and his father Swedenborgian – and he was relatively orthodox into his teenage years. This made the impression of speeches by Morality as Religion author W.R. Washington Sullivan and Stanton Coit especially strong, and after hearing the latter in the late 1890s, Stocker resolved to work for the Ethical movement.

Settling in Brighton in 1903, Stocker founded the Brighton and Hove Ethical Society in 1905. In spite of fluctuating finances and membership, the group continued for many years. Its objects were:

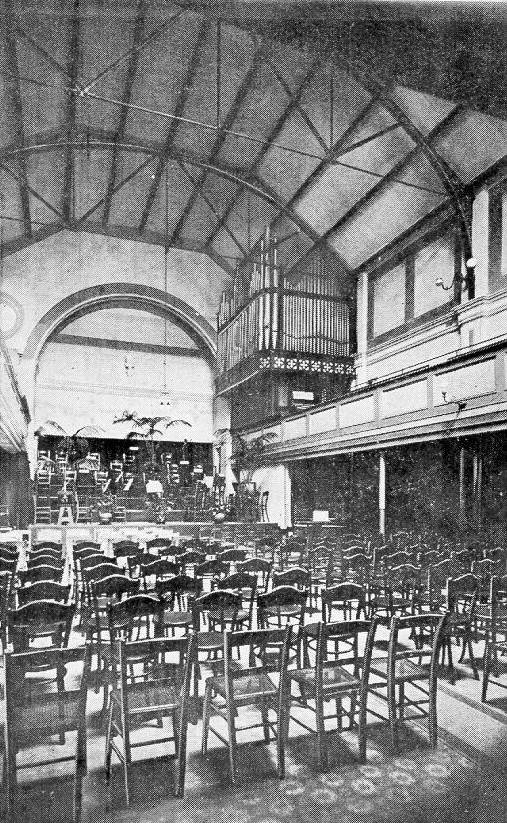

In 1918, Stocker returned to London and began working for the Hampstead Ethical Institute, becoming its president. He joined the council of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK), and edited its paper, The Ethical Societies’ Chronicle, from 1924. Throughout his work for the ethical movement, he lectured regularly, including at South Place Ethical Society and Stanton Coit’s Ethical Church.

In 1908’s Spirit, Matter and Morals, Stocker outlined his concept of ‘Rational Ethicism’, noting its indebtedness to the figures of Thomas Paine, Charles Bradlaugh, and G.W. Foote. In it, he described the role of careful reasoning and reflection in arriving at ideas of morality and integrity:

[W]hilst ethics would seek to inspire man with a love of the good… no less would rationalism arouse in him a reverence for the true, and seek thereby to encourage that strict intellectual sincerity which must lie at the root of all genuine progress, material or otherwise.

Stocker published numerous books on a wide range of subjects, including poetry, graphology, phrenology, philosophy, ethics, and social subjects. His wife, Helen Leslie Stocker (née Cash), was also a writer and ethical society member, and published two volumes of poetry. In a 1922 edition of Notable Londoners, Stocker’s recreations are listed as ‘Music (listening) and literature.’

Richard Dimsdale Stocker died in London on 23 July 1935 at the age of 58, and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium. Stocker had remained editor of the Ethical Societies’ Chronicle until a few months before his death. His obituary, printed in the Ethical Record in September of that year, lauded Stocker for carrying out ‘his work with loyalty and devotion’ and ‘writing every leading article [of the Chronicle] from the first number to May in this year.’

That faith has its legitimate functions and uses, even in this professedly rational era, must be apparent to the average observer. Though supernaturalism may have declined, confidence and trust are still as necessary as every between man and man; indeed, it may be truly affirmed that faith between two human beings is, if anything, a fairer and more beautiful thing than the faith which our forefathers reposed in the supernatural providence.

Spirit, Matter and Morals

Stocker’s work and writings emphasised what he saw as the central role of the Ethical movement: to unite people in pursuing a good and moral life. In Gustav Spiller’s history of the movement, Stocker was described as ’an admirable speaker… [who] often rose to a genuine eloquence’. In his role as founder of the Brighton society, president of the Hampstead group, and occasional deputy for Stanton Coit at the Ethical Church, Stocker occupied a prominent position in the organisation and promotion of the early humanist movement, promoting rationalism and fellowship above all else.

Conscious morality cannot exist in any being except so far as it can look behind, before, and around; and can […]

The difference and variety of our human family more and more seems to me to be a wise provision that […]

Humanism is a philosophy – one which gives us a coherent stance for living. We believe the humanist approach to […]

Avoiding alike mysticism and shallow denial, he was a true Agnostic, anxious not merely to beat down error, but to […]