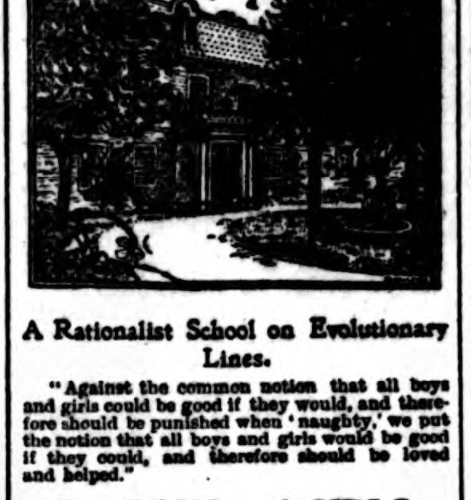

The Ruskin School Home was founded by socialist writer and teacher [Harry] Bellerby Lowerison (1863–1935) in Norfolk in 1900, following his dismissal from a post in a London school after publishing his criticisms of traditional schooling in The Clarion. The progressive and co-educational Ruskin School Home was advertised as being ‘a Rationalist School on Evolutionary Lines’, and focused on the physical and mental wellbeing of its pupils, inspired by the educational ideas of John Ruskin. Dispensing with Bible teaching and religious instruction, Lowerison’s pedagogical approach was notably humanist, emphasising scientific investigation, cooperation, and the development of compassion.

For many years prior to founding the school, Harry Lowerison (who adopted the forename Bellerby in 1910) had been a prolific contributor to the socialist Clarion newspaper. In its pages, in 1899, a letter from Lowerison appeared under the title ‘My Ideal School’, in which he laid out a vision for a school where ‘most of the work could be done in the open air, and sun and air and plain and wholesome food, utter cleanliness and healthful exercise shall be our doctor.’ Lowerison hoped to teach ‘the Laws of Health and the Exercises,’ ‘Habits of Gentleness and Justice,’ and to develop ‘the natural capabilities and talents of each individual child… so that each child may follow, happily and naturally, as far as may be, the calling by which he or she is to live’. Also central to Lowerison’s ideal was his assertion that he would ‘teach the dogmas of no religion.’ As a result of the publication, Lowerison was dismissed from his post as a teacher at Wenlock Road School, Hackney, without a reference.

The following year, with donations from The Clarion’s readers, Lowerison opened his own school in Hunstanton, Norfolk, moving in 1902 to nearby Heacham. Lowerison and his wife, Alice Mabel (née Dutton), ran the school together, combining ‘their great love for children’ with ‘forward looking ideas on education.’ In line with his socialist principles, Lowerison sought to make the school as deinstitutionalised as possible, with plentiful time spent outdoors and a cross-curricular approach to lessons.

Writing of the Ruskin School Home’s success in The Clarion in 1903, Lowerison again placed emphasis on its secular focus:

So the tide has turned, and parents write piteous letters to me, asking if I cannot engage one professing Christian teacher, so that their children may have the benefits of our system without being deprived of systematic Bible teaching. Failing this, they ask if I know of any Christian school run on our open-air lines. To such parents I always reply that my experience of Christians tends to show that they are not better than their neighbours, and that I am quite satisfied with my present staff. To avow oneself an Agnostic or Atheist demands some honesty of mind and firmness of purpose… One clergyman of the Church of England sends us his boy, asking no questions. His confidence will not be abused. I wish there were more as broad-minded as he. All the same, that boy will never believe in the damnatory clauses of the Athanasian Creed. The bogey tale of eternal hell cursed my childhood, and I’d break stones on the road rather than pass the horrible devil-worship on.

Ruskin School Home was at its busiest between 1909-10, with 50 pupils, but its fortunes declined after the First World War, and it closed in 1926. The Scottish educationist and humanist A.S. Neill, who founded Summerhill School in 1924, visited Lowerison’s school, and was likely influenced by what he saw there.

Bellerby Lowerison’s focus on the best development of the child, on free enquiry and natural exploration, and on the absence of religious doctrine in education, echoes that of other humanist educationalists like Alice Woods (1849-1941) and Frederick James Gould (1855-1938), who similarly advocated for progressive, co-educational, and non-religious schooling.

High House (location of Ruskin School Home) | Historic England

Bellerby Lowerison | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Heacham Heritage (for additional photos and information)

She was greatly gifted, and through her genial nature made friends everywhere. To the last she was an enthusiastic Rationalist, […]

I was educated among the Saints; and I now live, thank God, among Sinners. David Williams, Essays on Public Worship […]

[I] feel extraordinarily proud and extraordinarily lucky to be the child of a woman who from her early twenties was […]