If after this survey of the nature of illusions and delusions, we turn again to religious doctrines, we may reiterate that they are all illusions, they do not admit of proof, and no one can be compelled to consider them true or to believe in them… In the long run, nothing can withstand reason and experience, and the contradiction religion offers to both is only too palpable.

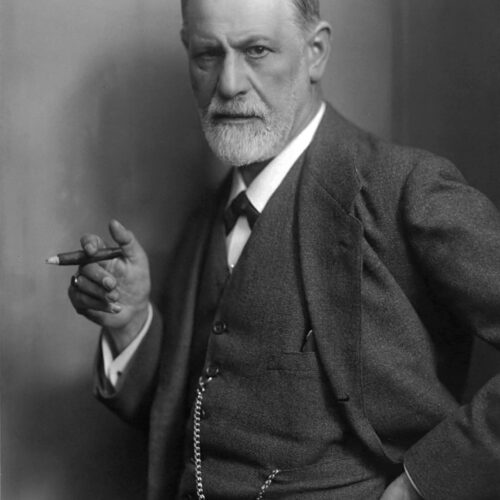

Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion (1927)

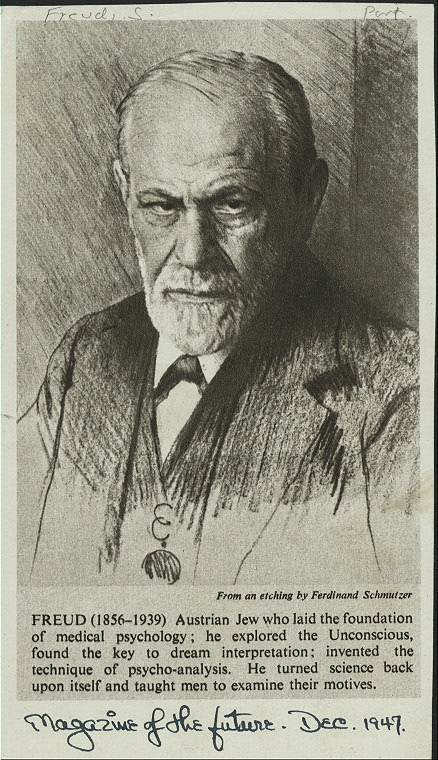

Austrian physician Sigmund Freud remains one of the most recognisable names in psychology: the founder of psychoanalysis, who helped bring the study of mental health to the public eye and mainstream media. Born into a largely non-observing Jewish family, Freud was a lifelong atheist, who wrote of religion as a comforting illusion, and became an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association.

Although aspects of Freud’s work are today considered controversial or outdated, his work profoundly influenced our understanding of the human psyche, and was of notable significance to members of the Bloomsbury Group. Like humanists today, Freud emphasised the ultimate power of careful observation, open discussion, and rational thought, prizing scientific investigation as the path toward truth and understanding.

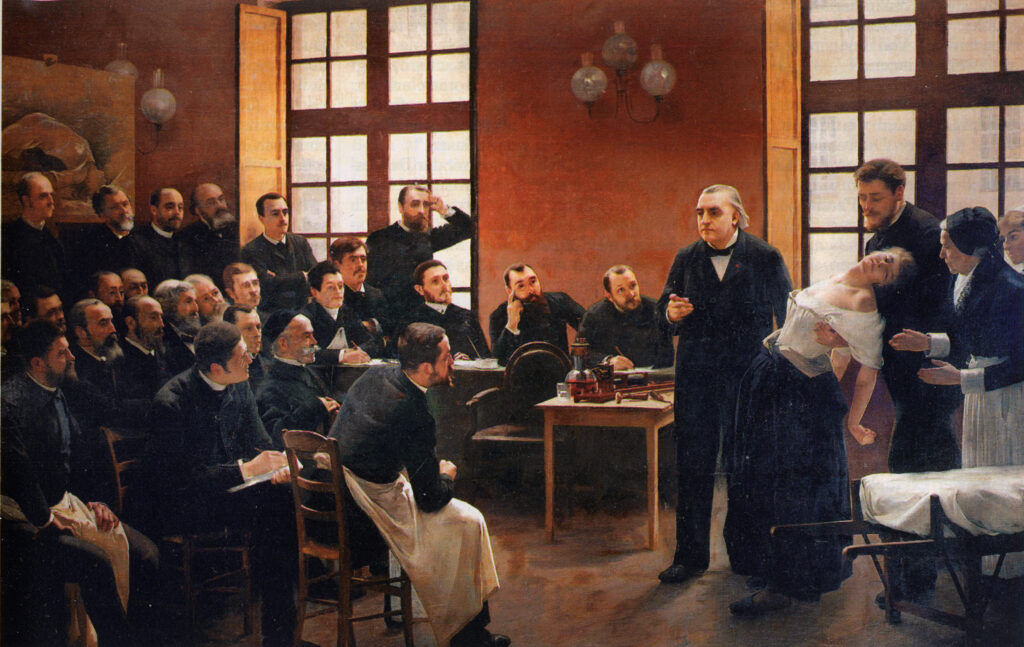

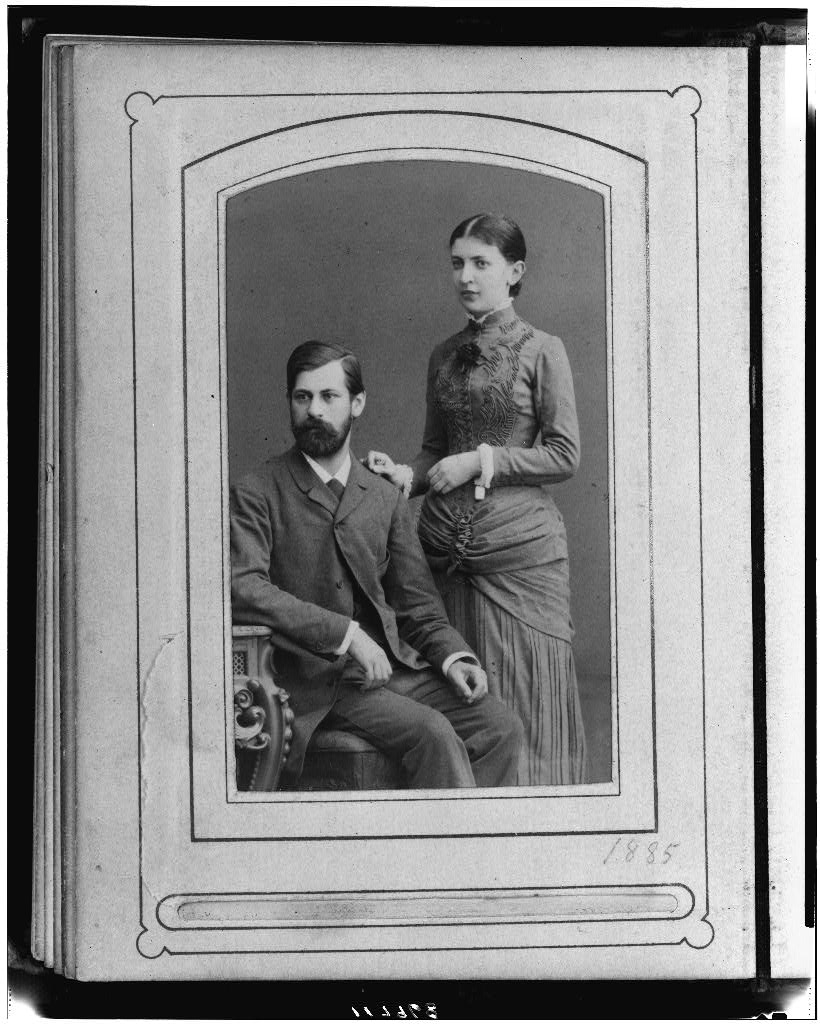

Sigmund Freud was born on 6 May 1856 in Freiberg, in the Austrian Empire (now modern day Czech Republic). Freud’s family were Jewish and in 1860 they moved from Freiberg to Vienna. In 1873 he graduated from Sperl Gymnasium before turning to a career in medicine and taking up study at the University of Vienna. He worked at the University with one of the leading physiologists of the time, Ernst von Bruke. Freud further expanded his medical knowledge and trained as a clinical assistant to psychiatrist Theodor Meynert and Professor Hermann Nothnagel at the Gernal Hospital in Vienna in 1882. In 1885 he was appointed as a lecturer in neuropathology as a result of the important research he conducted on the brain’s medulla. Later in the year he moved to Paris for 13 weeks where he studied at the Salpêtrière clinic. This marked an important turning point in Freud’s career as it was whilst in Paris that he first came across patients who were suffering from what was then described as ‘hysteria’.

It was Freud’s study of hysteria that paved the way for psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis refers to the theory of the structure and workings of the mind. He believed that simply by talking to the patient and allowing them to talk about their difficulties, it would cure them of their hysteria. The reason for this was that during his study of hysteric patients, Freud learned many of them had suffered from past traumatic experiences. This led Freud to further study post-traumatic stress.

Freud was not only fascinated by psychoanalysis but also social and cultural studies. In Freud’s later life he wrote various books criticising religion and the way it has impacted civilisation. He considered himself an atheist and wrote several books on the subject; Totem and Taboo (1913), The Future of an Illusion (1927), Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), and Moses and Monotheism (1939). In The Future of an Illusion he examined the origin and pull of religious ideas, concluding that:

…they are illusions, fulfilments of the oldest, strongest, and most urgent wishes of mankind. The secret of their strength lies in the strength of those wishes.

Freud viewed religion as a means of giving structure to social groups and enacting wider control. He believed that religion was an expression of underlying psychological neuroses and distress and the reason for people believing in divinity was their unconscious mind’s need for fulfilment. He saw God as a father-figure, belief in which allowed people to absolve themselves of their own guilt. However he did recognise the impact that religion had on personal identity and culture. Although an atheist, Freud was aware of how his Jewish background and own experience of anti-Semitism had shaped who he was. He said in 1925:

My language is German. My culture, my attainments are German. I considered myself German intellectually until I noticed the growth of anti-Semitic prejudice in Germany and German Austria. Since that time, I prefer to call myself a Jew.

Freud was a heavy smoker from a young age and developed cancer in the jaw in 1923 and although he had surgery he never fully recovered. When the Nazis took control of Germany in 1933, Freud’s work was involved in the Nazi book burnings which were carried out by the German Student Union. The burnings involved books, novels and work which was considered to be ideologically opposed to Nazism and was burnt on mass in public gatherings. Despite this Freud did not leave Vienna and was reluctant to leave mainland Europe. However when the Nazi’s annexed Austria in 1938 and anti-Semitism rose in Vienna, Freud fled the country to England. He settled in London and continued to treat patients and write until he became terminally ill from cancer.

Freud’s ‘stoical humanism’, wrote Humphrey Skelton for The Humanist in 1959, ‘sustained him through years of bitter struggle and physical pain’. At the end of his life, this same philosophy underpinned his decision to die on his own terms. He had, years earlier, requested that Max Schur, his personal physician, not prolong his life when there was no longer any sense in living. As such, at Freud’s request, Schur administered a lethal dose of morphine on 23 September 1939. A simple service took place three days later at Golders Green crematorium.

…if often he was wrong and, at times, absurd,

to us he is no more a person

now but a whole climate of opinion

under whom we conduct our different lives

W.H. Auden, ‘In Memory of Sigmund Freud’, 1940

Sigmund Freud’s theories of the mind helped pave the way for the study and understanding of mental health, and effected a radical shift in our perception of pyschology and behaviour. As Auden suggested in his poem on Freud’s legacy, his influence was so profound as to permeate our lives completely. And as Maria Konnikova has written:

Freud radically altered our self-conception and our relationship to ourselves, by forcing us to acknowledge how much our internal life affects our external one, how great a contribution comes from elements that we don’t understand or know.

Freud’s ideas on the origins of the religious impulse, and the comforting illusion religion provided, were a significant contribution to a tradition of scientific humanist thought, in which research and reason were the means of uncovering truth. They also served to highlight the powerful resonance of childhood influences on adult lives, not least in the realm of religion.

Freud was also a direct influence on members of the Bloomsbury Group, some of whom entered psychoanalysis with him. One of these was James Strachey, whose translations of Freud’s work, published in twenty-four volumes by Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press, remain authoritative. Leonard Woolf would later describe Freud as:

…extraordinarily courteous in a formal, old-fashioned way—for instance, almost ceremoniously he presented Virginia with a flower. There was something about him as of a half-extinct volcano, something sombre, repressed, reserved. He gave me the feeling… of great gentleness, but behind that, great strength.

I had long put on one side the purist pacifist view that one should have nothing to do with a […]

Humanism is less concerned with what to believe than with how to live. The meaning it gives to life lies […]

As well as being home to Conway Hall and its humanist library, Red Lion Square contains statues of two prominent […]

Humanists have principles too, but they are principles which do not refer to the existence of the supernatural. This is […]