What is this ban on abortion? It is a sexual taboo, it is the terror that women should experiment and enjoy freely, without punishment. It is the survival of the veiled face, of the barred window and the locked door, of burning, branding, mutilation and stoning; of all the pain and fear inflicted ever since the grip of ownership and superstition came down on women, thousands of years ago.

Stella Browne, speech to the Abortion Law Reform Association’s founding conference, Conway Hall, 1936

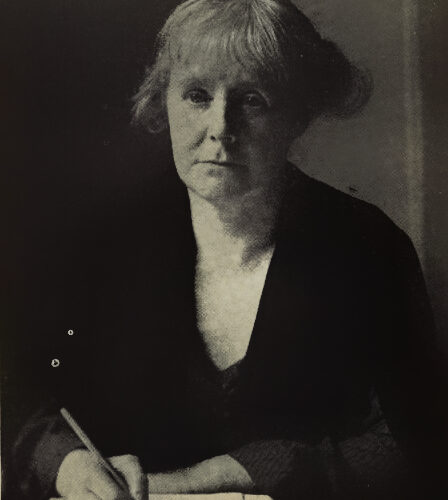

Stella Browne was a humanist, a socialist, and a feminist who campaigned tirelessly for women’s reproductive rights for over thirty years. An authority on human sexuality, she argued for easy access to effective contraception and the right to safe, legal abortion while insisting that the great variety in women’s needs and desires should be acknowledged and respected.

Stella Frances Worsley Browne was born in 1880 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Her father died when she was three and her mother then supported the family by running a small boarding house for single women. Browne was educated in Germany, at St Felix School for Girls, Southwold (where she was encouraged to learn by making her own enquiries and observations), and at Somerville College, Oxford where she absorbed a ‘progressive conception of women’.

After graduating, Browne worked as a teacher, a historical researcher, as the librarian at Morley College, and as a civil servant in the Department of Health. She then supported herself as a freelance book reviewer, work which gave her a deep knowledge of the scientific, medical, and psychological aspects of human sexuality. She joined the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology soon after its formation, and her paper ‘The Sexual Variety and Variability Among Women’, which argued that women’s sexual and maternal feelings could not always be satisfied within marriage, was published by the BSSSP in 1917.

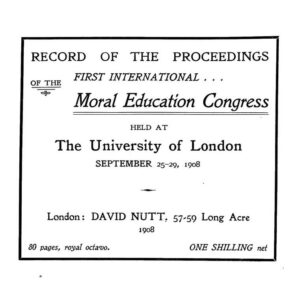

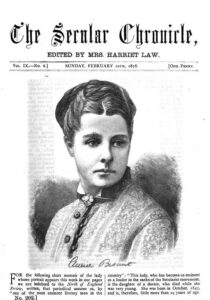

Browne also joined the Malthusian League and became an effective public speaker on its behalf, providing many women’s groups with badly-needed practical advice about birth control. She also addressed Ethical Union (now Humanists UK) and National Secular Society branches on such topics as ‘Birth Control Problems and Humanist Ethics’, and ‘Birth Control and the Right to Abortion’. These talks were so successful that some groups invited her back time and again. Browne’s humanism also led her to become active in the Humanitarian League, the Progressive League, and the Divorce Law Reform Union.

Browne began campaigning for abortion law reform in 1915, but progress was slow. It was not until 1936 that she was able to launch the Abortion Law Reform Association together with Dora Russell, Janet Chance, Alice Jenkins and other freethinking feminists. Despite being routinely denounced as ‘scarlet women’ and ‘village atheists’, the ALRA activists persisted and in 1937 ALRA gave evidence to the Inter-Departmental Birkett Committee on Abortion. ALRA argued for legalised abortion to reduce deaths in pregnancy, but Browne made her own submission to the committee, revealing her own abortion ‘as a matter of public duty’, and insisting that abortion was both an absolute right and an indispensable means of advancing human happiness.

If abortion were necessarily fatal or injurious, I should not now be here before you.

Stella Browne, in her submission to the 1937 Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion

Throughout her campaigning Browne promoted what she saw as a ‘rational humanist attitude’ to marriage and parenthood, for which birth control was essential, implying both responsibility and freedom for both partners. She believed that abortion should be available to any woman in the early stages of pregnancy as an absolute right because ‘our bodies are our own’, and she became convinced that the opposition she encountered was not based on a concern for human well-being but grounded in religious and superstitious beliefs.

Following the outbreak of the Second World War, Browne moved to Liverpool for family reasons. Nevertheless, she kept in close touch with ALRA until her death in 1955. Her obituary described her as having a ‘remarkable blend of moral earnestness, crusading fervour, and a light-hearted determination to get the best out of life’. Alice Jenkins recalled that when Browne first raised the question of abortion at a public meeting she was met with ‘a silence that could be felt’ – a testament to Browne’s boldness and bravery at a time when the subject of abortion remained deeply taboo.

Browne was for twenty years the only person campaigning for the legalisation of abortion in Britain and she never compromised on her core demand: that women should have access to safe, legal abortion by right. ALRA continued to campaign after her death, and was influential in the passing of the Abortion Act 1967, but even this did not provide the absolute right to abortion which Browne had demanded. Nonetheless, alongside other pioneering humanist women of her generation, Browne’s tireless activism had helped to usher in significant reform, even in the face of considerable opposition.

Fellow humanist, activist, and friend Ashton Burell described Browne as ‘tough, humorous, forthright, affectionate, courageous and sincere’, a description which speaks to the combination of fervent feminism, and compassionate humanitarianism, which animated her life. As her biographer, Lesley A. Hall, concluded:

…in spite of all we do not and possibly cannot know, Stella Browne was a remarkable and intriguing woman. She had an impact on other lives which resonates onwards.

Lesley A. Hall, The Life and Times of Stella Browne: Feminist and Free Spirit (2011)

Sheila Rowbotham, A New World for Women: Stella Browne – Socialist Feminist (1977)

By Paul Ewans

…no child should be made ashamed or uncomfortable on account of his father’s opinions, or lack of opinions, on subjects […]

To have thus assuaged the temper of controversy, to have softened much deep-seated prejudice and to have disposed some of […]

Not by the Creed but by the Deed. Motto of the Society for Ethical Culture of New York, founded in […]

The object of Secularism is the promotion of human happiness in this world… [The Secularist] believes the surest way of […]