I have no desire… to bring the religion or the laws of this country into contempt, although I am a believer in no kind of religion whatever, nor do I like the laws under which I live; but all I wish for on the score of religion is, that it be brought to the touchstone of free discussion, and that there shall be no persecution for matters of opinion.

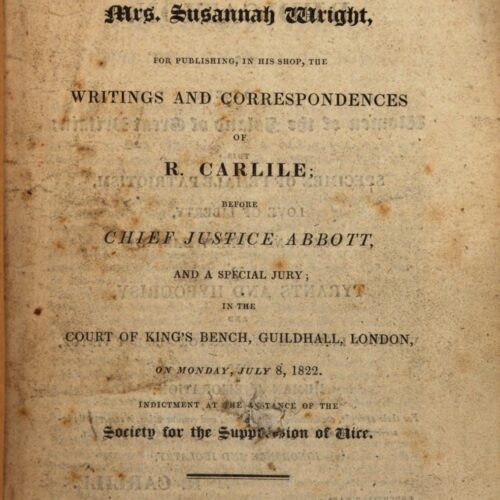

Report of the Trial of Mrs Susannah Wright, 1822

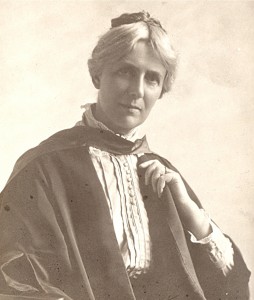

Susannah Wright was an ardent defender of free press and free discussion, who accepted ridicule and imprisonment in the name of upholding these fundamental rights. An involved radical and eloquent speaker in her own defence, Wright was initially imprisoned for her role in selling works from Richard Carlile’s bookshop, and was described by him as ‘by far the most interesting woman in the country.’ Wright’s story is one of the radical and freethinking woman, fostered by a circle of like minded friends and colleagues, who became a noted champion for their shared causes: causes shared by humanists today.

Susannah Wright was born Susannah Godber in the last decade of the 18th century in Nottingham, where she was a lace worker. Influenced by the reformers of her hometown, Susannah’s own spirit of rebellion was ignited long before her move to London, though it was there that she would gain the notoriety she eventually achieved. Susannah married William Wright in 1815, who shared her interest in radical politics, and the two were regular attendees at the gatherings of fellow radicals and other ‘Atheistical friends’.

Following the arrests and imprisonments of Richard Carlile, his wife Jane, and sister Mary-Ann in the early 1820s for selling materials deemed blasphemous and seditious, Susannah responded to requests for help in keeping the Carliles’ radical bookshop open. In 1821, after an agent for The Society for the Suppression of Vice was sold a prison-penned tract by Richard Carlile, Wright herself was charged with blasphemy, appearing for the first of three court appearances in December of that year. Having been released on bail, Wright’s next trial was scheduled for July 1822, enabling time for the preparation of her own vigorous and impassioned defence.

Susannah Wright was charged with ‘unlawfully’ and ‘wickedly’ selling ‘a certain scandalous, impious, blasphemous, and profane Libel, of and concerning the Christian Religion’. To this, she responded:

the conduct of my persecutors is that which brings their religion into contempt, by proclaiming to the people of these realms, through these persecutions, that it cannot stand the test of examination and free discussion… It is a moral impossibility that truth can be brought into contempt by ever so strict a scrutiny, or by sarcasm, or ridicule, however poignant… It is persecution by brute force alone that can impede its progress upon the human mind: to that my persecutors resort to shelter their religion from examination and free discussion, and that strengthens my infidelity towards it.

Wright’s defence lasted almost four hours, and included a warning to judge, jurors, and onlookers that ‘If you, Gentleman, to day, say, that I have published what is blasphemous and profane, you will be despised for it to-morrow.’ Nevertheless, she was pronounced guilty and sentenced (at a further hearing four months later) to ten weeks’ imprisonment in Newgate prison.

Significantly, Wright’s defence highlighted the classism she perceived in this wave of prosecutions for blasphemous libel, arguing:

It is notorious that those who are denominated the higher class or the aristocracy throughout Europe, have boasted of an infidelity towards all religion for more than a century past, and it is only within these few years, since the labouring useful classes have begun to have their eyes opened about the matter, that the clamour about blasphemy and profaneness has been raised by the hypocrites. Infidelity has been viewed as a luxury by this pretended higher order of beings, and which, like all other luxuries, they wish to keep from the useful and productive class of mankind.

Susannah Wright later returned to Nottingham and established her own freethought bookshop. Her date of death is unknown.

‘I look upon her as by far the most interesting woman in the country, and one who has done more public good than any other one.’

Richard Carlile in Republican, 24 September 1825

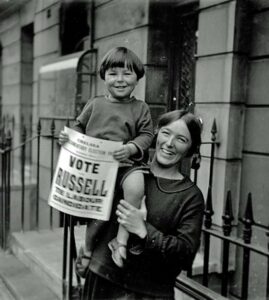

The example of Susannah Wright challenges the commonly held notion that 19th century radicalism was the sole domain of men. In the case of her prosecution, and in the words of her defence, we can see that the causes of free press, free discussion, and the right to religious scepticism were concerns shared by men and women alike, as they continue to be among humanists today.

It is in fact a strength, not a weakness, of a secular morality that it must stand upon its own […]

Our interest, it seems to me, lies with so much of the past as may serve to guide our actions […]

I see this kind of love – the empathy that should be common to all living creatures – rather than […]

Mackenzie Hall is a community space in the village of Brockweir, Gloucestershire, given by Millicent Mackenzie in memory of her […]