I have a strong faith and I love mankind.

Lord Willis, debate on the Broadcasting Bill in the House of Lords, 18 July 1990

I do not believe in God but I believe in good. I believe in God with a double ‘o’.

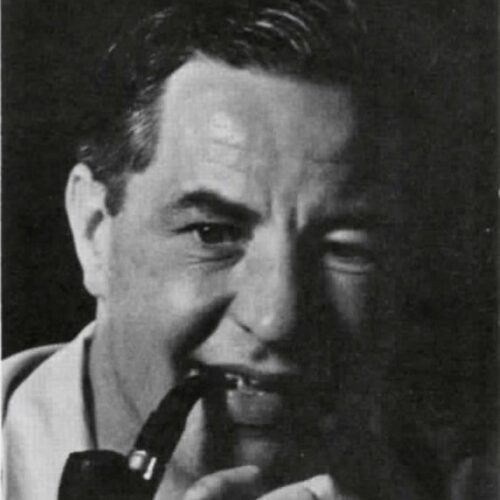

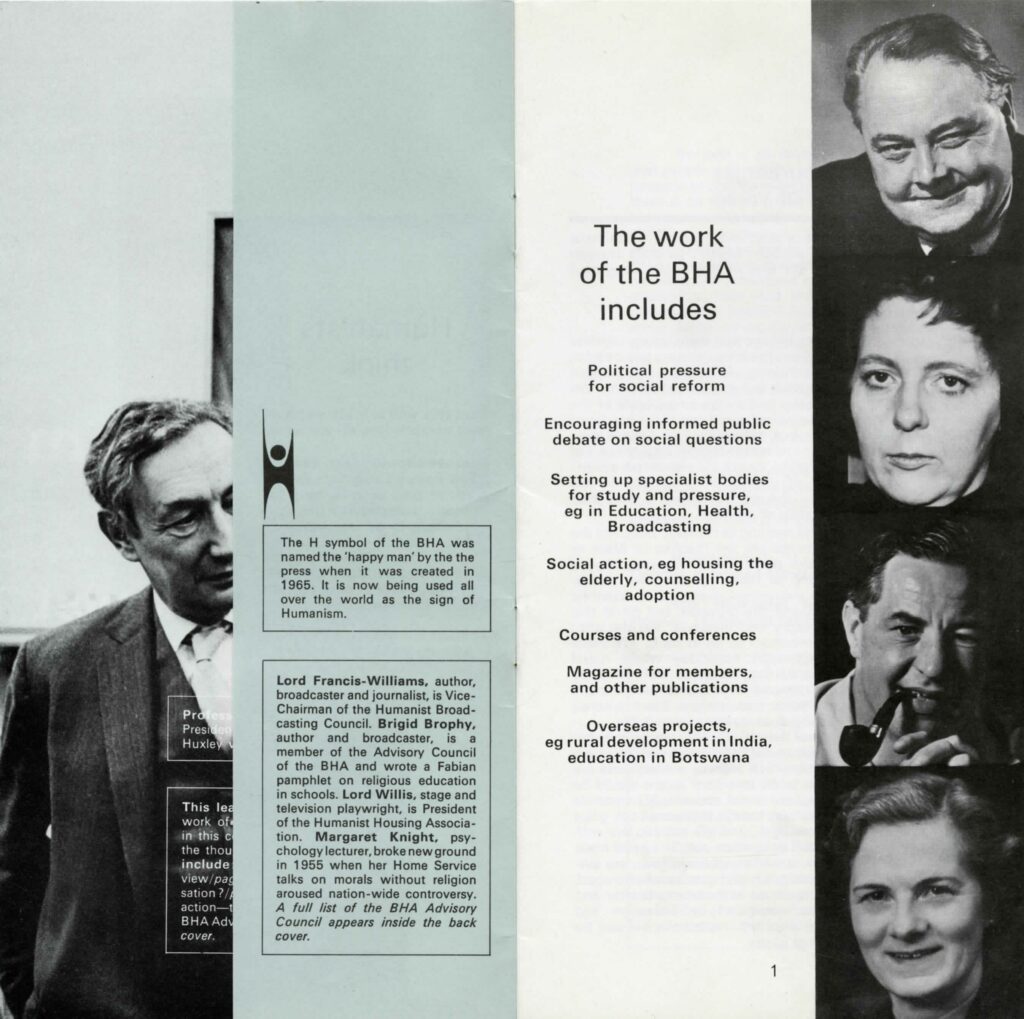

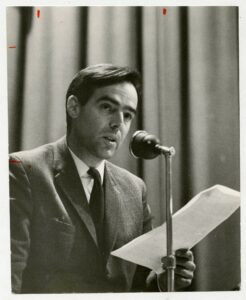

Writer and activist Lord Willis was, in the words of New Humanist magazine, ‘a true humanist immersed in many areas of life’. A member of the Advisory Council of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK), Willis was also an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association, President of the Humanist Housing Association, a member of the Humanist Parliamentary Group, and a campaigner alongside Brigid Brophy and Maureen Duffy to achieve the Public Lending Right. He gave powerful voice to humanist issues in the Lords, speaking against censorship and blasphemy laws, Section 28, and for greater balance of religions and beliefs in broadcasting.

Reproduced below is the obituary published for Ted Willis in New Humanist magazine, Spring 1993.

TED WILLIS was an immensely successful writer — creating plays for television, cinema and stage. He is best known for his TV series Dixon of Dock Green which lasted 25 years. He also had an impressive political career in the House of Lords.

He was born in Tottenham and was brought up in poverty, met with good spirits and endurance by his indomitable mother. Two aspects of his childhood point to his future career — his ability to make up stories and his love of the cinema. The newsagent with whom he worked on newspaper deliveries was a source of thoughtful conversations and talked to him about Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus, and in his teens he devoured Winwood Reade, Shaw and Wells.

After leaving school at 14, he was unsuccessful at finding a steady job (it was during the Depression years) and became involved in politics. He eventually became the national organiser for the Labour League of Youth and edited their paper Advance. He was involved in disputes with the Blackshirts and regarded a fractured arm as a trophy — he was to hate anti-semitism all his life. He visited Spain three times during the Civil War, being involved in food distribution. He was regarded as an extreme young socialist and in due course became a Communist (which he abandoned when Stalin refused to allow Russian war brides to rejoin their husbands in Britain). He began writing scripts for war propaganda and after the war was involved with the Unity Theatre for which he wrote several plays.

The many plays, scripts and later novels all demonstrate his vitality, forthrightness and ability to capture a wide range of ordinary and extra-ordinary people.

After the war a string of successes included The Blue Lamp and Woman in a Dressing Gown. Dixon of Dock Green was a policeman resurrected from The Blue Lamp to become the star of one of the most successful television series ever produced. It lasted 25 years and Willis continued writing many of the scripts throughout its long stay. It provided a much more benign view of the police than is available on the media today. He was particularly good at documentary-style plays and often travelled to undertake research. Another very successful play was Hot Summer’s Night about a love affair between the daughter of a trade union leader and a black man — one of the first plays to raise such race issues. The many plays, scripts and later novels all demonstrate his vitality, forthrightness and ability to capture a wide range of ordinary and extra-ordinary people.

In 1963, Harold Wilson made him a life Peer and he became Lord Willis of Chislehurst. One of the first issues he spoke on in the House of Lords was the abolition of the Lord Chamberlain and theatre censorship.

His second career was as a politician. He had been offered a safe Labour seat in 1945, but declined it on the grounds that he preferred to continue as a writer. In 1963, Harold Wilson made him a life Peer and he became Lord Willis of Chislehurst. One of the first issues he spoke on in the House of Lords was the abolition of the Lord Chamberlain and theatre censorship. Another service he did to writers was to support the Bill creating a Public Lending Right — a measure due largely to Brigid Brophy and Maureen Duffy. He also stood for authors’ rights as President of the Writers’ Guild from 1958-68 and 1967-79. Among humanist causes he spoke for were reform of Sunday trading law, abolition of blasphemy law and opposition to the anti-homosexual Clause 28. In his last major speech he protested against the decline of the public library — a prescient voice.

In July 1990 he moved an amendment to the Broadcasting Bill proposing that broadcasting should include “the other great religions of the world, in a balanced way and the viewpoint of agnosticism and humanism” (New Humanist, Vol 105, No 3, October, 1990). He spoke of his beliefs:

I happen to be an atheist. I am not an agnostic. An agnostic is simply a shamefaced atheist. I am a total non-believer. I do not apologise to the Committee for that… I lost my faith when I was about 14. I went to the bottom of the garden and said, “If there is a God, please lift that dustbin lid. Let that dustbin lid rise and that will prove him to me.” I am sure we have all done that at some time or another. Of course God ignored me and the dustbin lid did not rise.

More seriously, my faith was lost in the Holocaust during the Second World War. I could not believe that a God could exist who would allow such things to happen…

I have a strong faith and I love mankind. I do not believe in God but I believe in good. I believe in God with a double ‘o’. Therefore, I believe that it would be wrong narrowly to limit television to the Christian religion. There are millions of people in this country who have different views. Even if they have no views they should be exposed to all the great philosophies and the great thinking that goes back for thousands of years.

He described himself as a “first-rate second rate author” — a modest self-appraisal. His friendliness, good humour and forthrightness made him a first-class person.

He wrote two volumes of autobiography: Whatever Happened to Tom Mix (1970) and Evening All: Fifty Years Over a Hot Typewriter (1991).

Willis was a true humanist immersed in many areas of life. He described himself (Evening All) as a “first-rate second rate author” — a modest self-appraisal. His friendliness, good humour and forthrightness made him a first-class person.

Mackenzie Hall is a community space in the village of Brockweir, Gloucestershire, given by Millicent Mackenzie in memory of her […]

Humanists believe that this is our world, our responsibility, our possibility. If you agree, would anyone know? Peter Draper, ‘Values […]

It is with a feeling of considerable deprecating delicacy that I venture to write of this woman, whom I so […]

I am a feminist, a rebel, and a suffragist – a believer, therefore, in sex-equality and militant action. I desire […]