The Open University was founded in 1969 with the ambition of providing access to higher education for people who had previously been unable or prevented from attending traditional universities. Prime minister Harold Wilson had spent several years working on the idea of a ‘University of the Air’ which would utilise technological advances to substantially improve educational opportunities for the masses. When Labour came to office in 1964, he appointed Jennie Lee as Minister for the Arts and tasked her with establishing the new university. Lee instilled the new institution with her humanist values of equality, universalism and scientific advancement, and today the OU teaches around 170,000 students, making it the largest HE provider in the UK.

From the 1920s onwards, the idea that radio and television could bring higher education to a wider audience slowly began to gain traction. As leader of the opposition, Harold Wilson had been inspired by the pioneering work of the Advisory Centre for Education and the National Extension College, which had been set up by sociologist Michael Young in 1960. Wilson believed that the ‘white heat of technology’ would provide the impetus for wide-ranging social change in the UK, including a transformation of adult education. After winning the general election of 1964, Wilson identified the best candidate to make this vision a reality.

Jennie Lee had grown up in a working class family in Fife, Scotland. After training as a teacher, she became an MP in 1929, married fellow Labour MP Nye Bevan in 1934 and worked at the Ministry of Aircraft Production during the Second World War. As Minister for the Arts from 1964 until 1970 she would achieve notable success in abolishing censorship and strengthening the arts industry, as well as leading the establishment of the Open University.

Lee showed considerable leadership and persistence to overcome various levels of opposition to the plan. The Ministry of Education and the Treasury provided no initial support, believing the idea to be unnecessary, unfeasible and too expensive. Even members of the cabinet were largely indifferent, or indeed actively hostile. One of her first acts in post was to set up an Advisory Committee, which she chaired, and then to develop plans to establish the university, which were included in Labour’s 1966 manifesto. The cabinet set up a Planning Committee in 1967, which drafted the OU Charter and Statutes and appointed the founding Vice Chancellor, Walter Perry, in May 1968. By insisting she report only to the prime minister and negotiate financing directly with the Treasury, Lee was ultimately able to obtain the funds and backing necessary to see the university created by Royal Charter on 23 April 1969.

The report of the Planning Committee laid out many of the principles that have informed the approach of the OU’s founders. It described the social, economic and political restrictions that prevented the majority of people from higher attainment and expressed a clear desire to open up universities beyond a privileged minority. It had two clear objectives: improving the economic conditions of the country by creating a more educated workforce and ‘the personal fulfilment and happiness of individual citizens’. The new university would complement rather than compete with existing institutions and make no academic compromise while pursuing its vision of widening access.

The creation of the new university coincided with the development of the new city Milton Keynes. It was decided that the synergy between these two new ideas – both projects aimed at building a better future by improving aspirations for the masses – made Milton Keynes the perfect home for the OU and the Walton Hall Campus was completed in October 1969. In its first year the OU enrolled 25,000 students, who were among the first to experience new methods of home study, including via science home experiment kits, television and radio programmes, and printed and posted course materials. In an unfortunate twist of fate, UK postal workers went on strike for a significant part of the first year of operation. Nevertheless this new method of study proved successful and the OU continued to grow over the following decades. Advances in computer technology continued to improve students’ home study experiences throughout the 1980s and 1990s, while courses were also made available to students in other countries around the world. The advance of the internet then transformed the ability of hundreds of thousands of students to study at home, taking the number of students to have received an education from the Open University past the milestone of two million.

The mission that the university has followed for over fifty years was perhaps best described by its first Chancellor Geoffrey Crowther:

We are open, first, as to people…

We are open as to places…

We are open as to methods…

We are open, finally, to ideas…

By Simon Hilditch

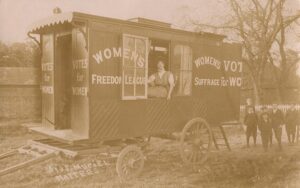

Dare to be free. Slogan of the Women’s Freedom League The Women’s Freedom League (WFL) was a militant suffrage organisation, […]

Girton College at the University of Cambridge has educated and employed a host of remarkable humanists and freethinkers, many of […]

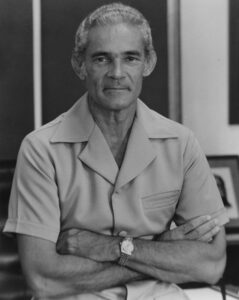

I like life with its mysteries. I don’t need my imponderables filled in for me. Michael Manley quoted by Rachel […]

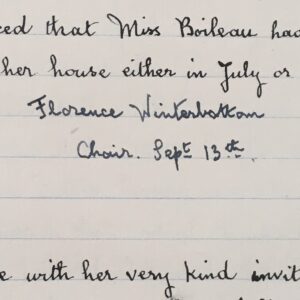

No one who came in contact with her failed to recognize in her fearlessness, honesty for the sake of honesty […]