The Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK) was formed in 1896, joining together existing ethical societies for fellowship and the furthering of their shared aims. The focus of the Union, as it had been for all of the ethical societies formed since the UK’s first a decade earlier, was the promotion and practice of morality without reference to theological ideas, emphasising a ‘purely human and natural’ basis for ethics and action. The Union would later become the Ethical Union, and later still the British Humanist Association, but its central humanist values of reason, compassion, and living well have remained the same since those earliest days.

From the creation of the West London Ethical Society in 1892, the intention to create a union of ethical societies ‘for the more effective carrying out of objects common to them all’ was written into the group’s aims. On 12 November 1895, at the invitation of the East London Ethical Society, delegates from the North, South, West, and East London Societies gathered at Devonshire House Hotel to discuss the notion of a federation. Four further meetings resulted in a ‘Scheme of a Constitution for an Ethical Federation’, which the Societies approved, and the first meeting of the Council of the Union of Ethical Societies was held on 30 April 1896.

The Union adopted for its aims, with minor adjustments, those of the West London Ethical Society. These were:

The Union then held its first annual Congress on 5 July 1896, presided over by Elizabeth Schwann.

Among the special objects of the Union, were a closer connection between societies, training and payment for ethical teachers and lecturers, the provision of ethical classes for children, and the publishing and distribution of relevant literature. Over subsequent years, amendments and additions were made to the aims and objects, including to explicitly state the development of morality free from theology, and to recognise the international concerns of the Union. The international element, however, was present from the year of the Union’s formation, which also saw the first congress of the International Ethical Union, in Zurich. By 1906, a single ‘General Object’ was adopted: ‘to advocate the supreme importance of the knowledge, love and practice of the right’.

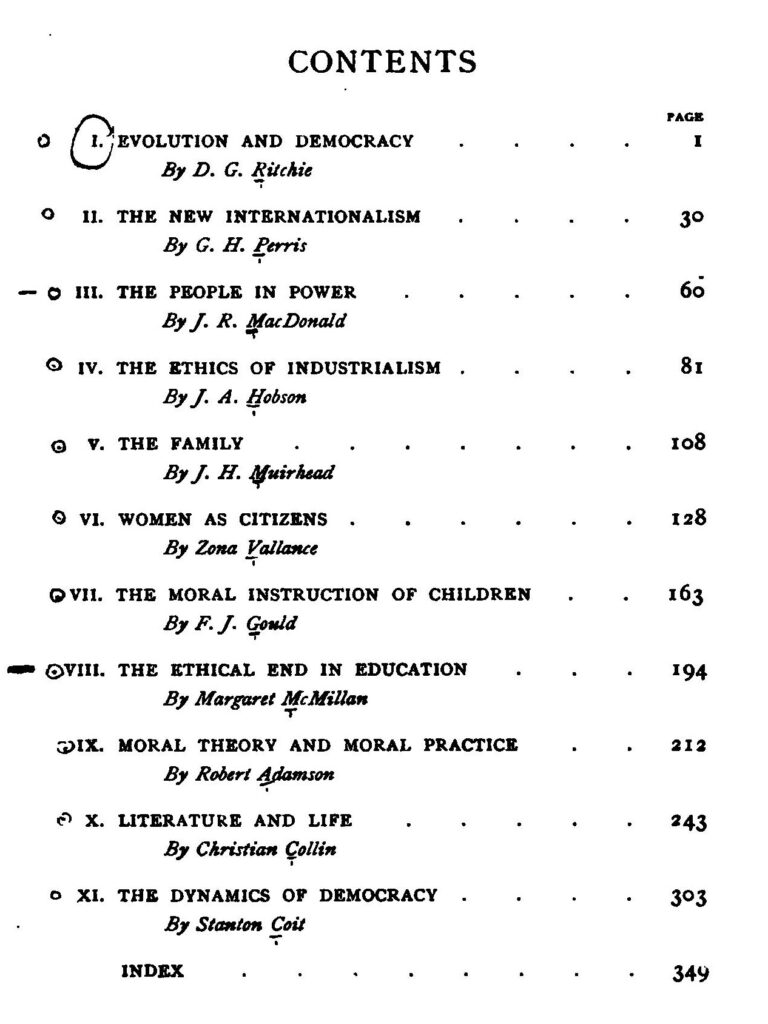

A series of lectures delivered in the first year of the Union’s existence included: Emilie Michaelis, J. J. Findlay, Alice Woods, F. J. Gould, J. H. Muirhead, M. E. Crees, Francis Warner, and Stanton Coit. The central concerns and activities of the Union (as well as many of its prominent figures) can be well summed up by the contents of its 1900 publication Ethical Democracy: Essays in Social Dynamics.

The 1890s saw the creation of the Moral Instruction League, and the Society of Ethical Propagandists, both of which represented the Union’s concern with education and the wider promotion of secular ethics. Zona Vallance was the inaugural Secretary of the Moral Instruction League, which held its first meeting on 26 January 1898. It advocated for non-theological moral education in schools, challenging the use of the Bible, and the assumption that most parents were content with the present system of religious instruction. The Society of Ethical Propagandists, formed by Stanton Coit in 1898, worked to promote the aims of the Ethical movement through lectures and published material, and included leading figures of the Union. Among these were Coit himself, Norwegian literary historian Christian Collin, prominent secularist Joseph McCabe, future Prime Minister Ramsay Macdonald, future Ethical Union President Harry Snell, moral education pioneer F.J. Gould, and Labour politician William Sanders.

The first decade of the 20th century witnessed the growth of the Ethical movement and a continuous increase in new societies. 1906 saw the peak number of societies affiliated with the Union at one time (26), although over 70 individual groups emerged in total, 46 of which were affiliated with the Union. The societies and their members continued to play an active role in progressive causes and social reform, not least in the realm of women’s suffrage. Many members were involved in the Women’s Freedom League, formed in 1907, and the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, two co-founders of which (Laurence Housman and H.N. Brailsford) were leading figures within the Union. Education continued to be at the forefront of the Union’s concerns, and the First International Moral Education Congress took place in 1908, bringing together delegates from across the world to discuss the necessity of non-theological moral instruction in schools.

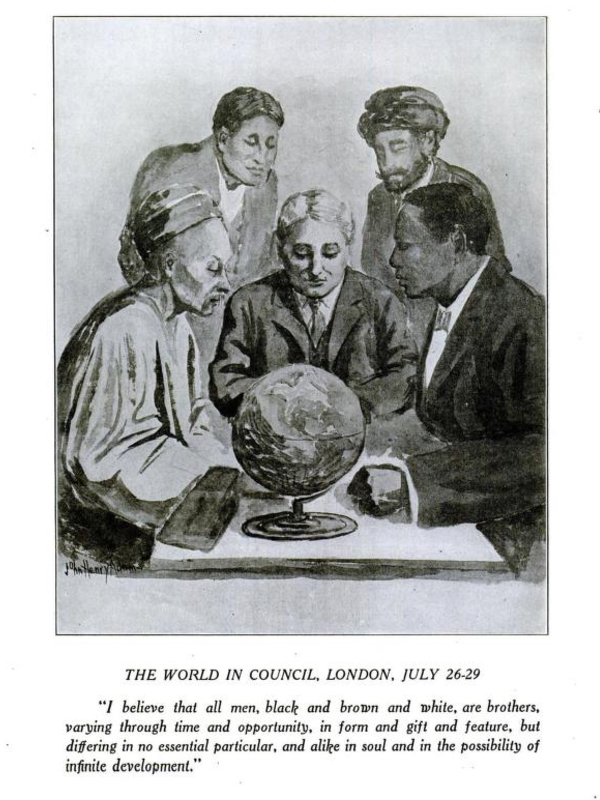

During the 1910s, the Union continued to be actively involved in encouraging international cooperation and efforts toward peace. The First Universal Races Congress of 1911, organised by Gustav Spiller, brought representatives from over 50 countries together to discuss international race relations, and to encourage ‘between them a fuller understanding, the most friendly feelings, and a heartier co-operation’. The outbreak of the First World War meant that the First Universal Races Congress was unfortunately also the last, but the Union of Ethical Societies and its members worked actively to bring about peace both during and after the war. This included providing assistance to refugees fleeing Nazism, prison visits to non-religious conscientious objectors, and active service at home and abroad. Many were closely involved in the League of Nations and its predecessor bodies, notably Gilbert Murray: Vice President of the League of Nations Society from 1916, and Chairman of the League of Nations Union from 1923. Wartime also saw the creation of the Women’s Group of the Ethical Movement, who published a manifesto in 1915 emphasising the role of women, and of humanist values, in bringing about peace.

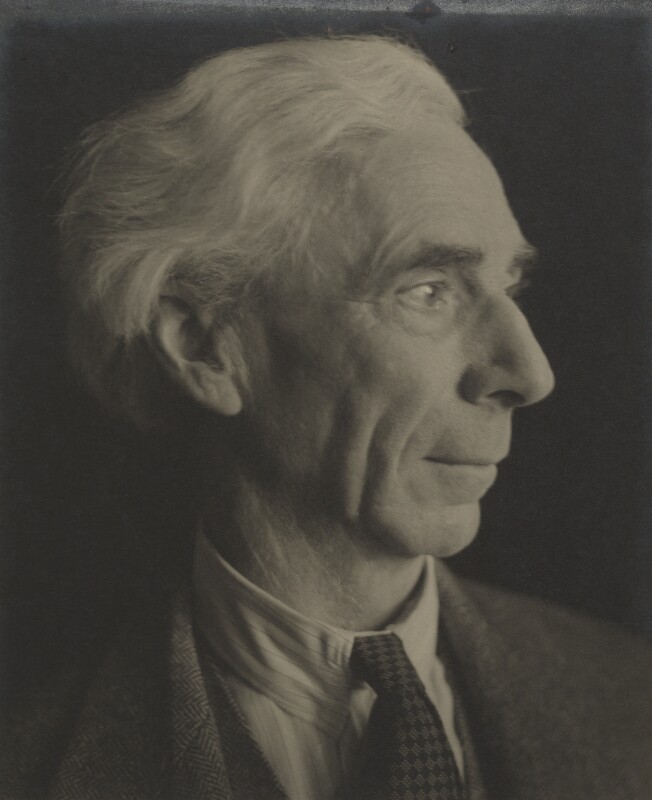

In 1920, the Union of Ethical Societies became The Ethical Union. In 1928, it was incorporated, giving all registered subscribers the rights to vote, and to initiate business for the agenda of Congress (as opposed to just the representatives of individual societies). Bertrand Russell’s ‘Why I am Not a Christian’ speech, delivered in Battersea Town Hall in 1927, gave powerful expression to the central humanist ideals of reason, compassion, and looking honestly at the world as it is and could be. In 1929, the South Place Ethical Society officially opened its new home at Conway Hall, which in 1938 hosted the International Congress of the World Union of Freethinkers.

The 1950s and 1960s were a period of adaptation and evolution for Ethical Union, including collaboration with the Rationalist Press Association and South Place Ethical Society, in which Harold Blackham played a leading role. A Humanist Council was established, and a meeting in 1957 led to the launch of the Humanist Association to investigate amalgamation. The Humanist Association was replaced in 1959 by a coordinating Humanist Council, and in 1963 the RPA and Ethical Union sponsored an ‘umbrella’ British Humanist Association. Its inaugural meeting took place in 1963 at the House of Commons. The Ethical Union’s loss of charitable status forced the RPA to withdraw from this umbrella organisation. The Ethical Union formally changed its name in 1967 to the British Humanist Association , which continues today as Humanists UK.

These two decades also saw the introduction of a variety of efforts to apply humanist values to wider social concerns, including the provision of services for the non-religious in areas unduly governed by religious bodies. The Ethical Union Housing Association, Humanist Broadcasting Council, Humanist Counsellors programme, and the Agnostics Adoption Bureau were all established, demonstrating an ongoing active commitment to social change. The formation of the International Humanist and Ethical Union in 1952 (now Humanists International) also symbolised a continuing commitment to the promotion of humanist values on a global scale. In 1969, the British Humanist Association organised a conference on the Open Society and showed, as described in the annual report, the ‘BHA leading discussion of the issues that face our democracy’.

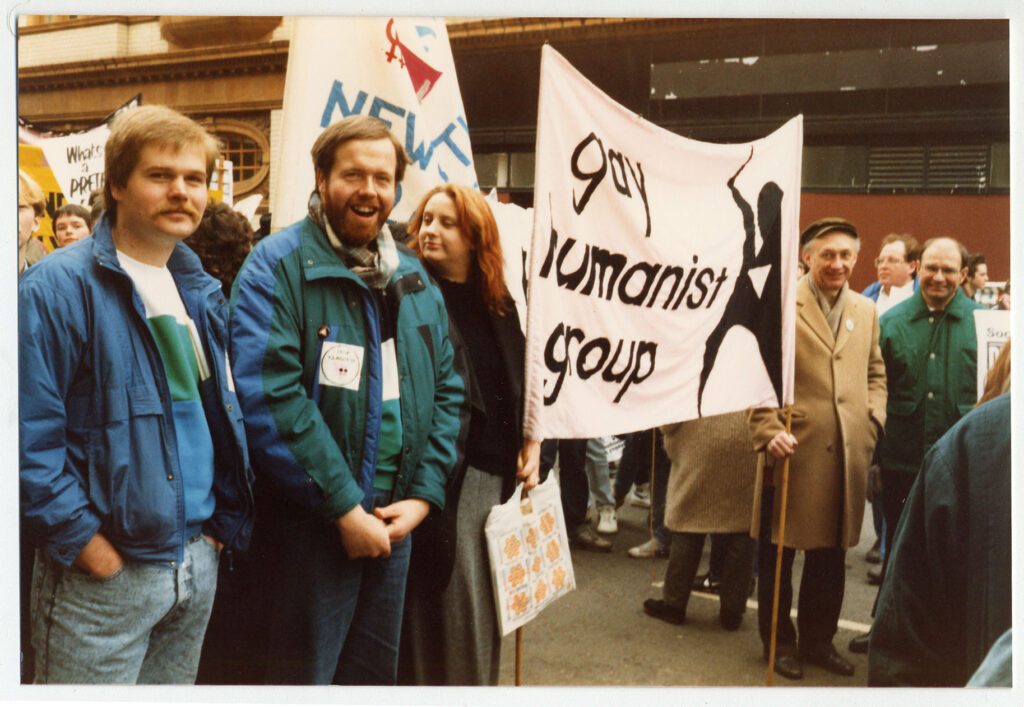

Over subsequent decades, the British Humanist Association tirelessly championed many of the causes still central to the work of Humanists UK for an inclusive, caring, and rational society. They continued to provide a voice for the non-religious in matters of education, including the efforts of Harry Stopes-Roe for the teaching of humanism as a ‘life stance’. The Gay Humanist Group was formed in 1979, fighting discrimination, creating a supportive community, and further developing the humanist provision of ceremonies for LGBTQ people. A network of trained celebrants continued to grow, as did that of non-religious pastoral carers in prisons and hospitals. The BHA were prominent and pioneering voices in women’s rights, including in areas of reproductive health, contraception, and abortion. Many of the more recent campaigning successes, and ongoing efforts for progressive and compassionate change, can be seen on the website of Humanists UK.

Universal rights are exactly that, universal, and one should not suddenly acquire different rights after a certain number of birthdays. […]

The British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology was officially formed in April 1914, ‘for the consideration of problems […]

I have been the more bold in exposing my opinion because I believe it to be the dictates of truth […]

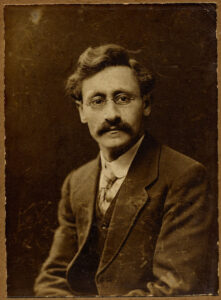

Chapman Cohen was a tireless champion of freethought, and a prolific writer and lecturer for the secularist cause. President of […]