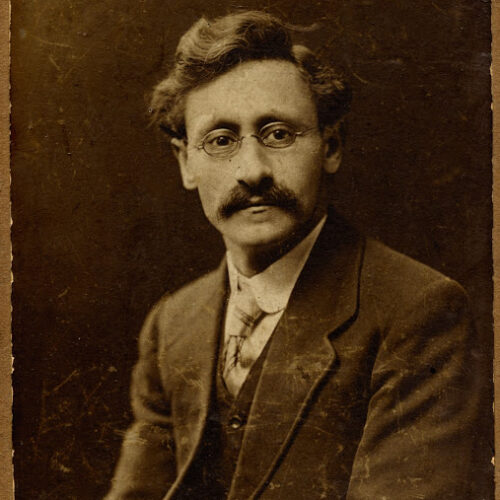

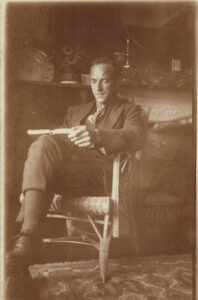

Chapman Cohen was a tireless champion of freethought, and a prolific writer and lecturer for the secularist cause. President of the National Secular Society, and editor of The Freethinker, for over three decades, he was an influential figure in the promotion of humanist values, admired as an eloquent challenger to superstition of all kinds.

Cohen was born on 1 September 1868, in Leicester, to a Jewish family, although his upbringing was remarkably free of religion. As he put it himself, ‘In sober truth I cannot recall a time when I had any religion to give up’. From an early age he was a voracious reader and as a teenager was already familiar with the writings of Spinoza, Locke, Hume and Berkeley. His route to atheism was different from his predecessors. Fierce rejection of religion and criticism of the absurdities and contradictions of The Bible were not for him. His objections were analytical, sociological and philosophical and this was the starting point for his lecturing, debating and writing for the rest of his life.

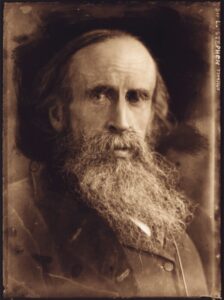

In 1889 Cohen moved to London and was walking in Victoria Park, a venue for open air meetings and speakers, when he witnessed a speaker being opposed by an old man who suffered from a speech impediment. The lecturer replied by mimicking the old man’s speech. When he was finished he invited opposition, an invitation Cohen accepted. Soon afterwards he joined the National Secular Society and became a lecturer. He briefly became editor of the Bradford Truthseeker but by 1897 was writing for George William Foote’s Freethinker. He soon became assistant editor and, as Foote’s health declined, took an increasing responsibility for the newspaper. When Foote died in 1915 it was inevitable that Cohen would succeed him both as President of the National Secular Society and editor of The Freethinker.

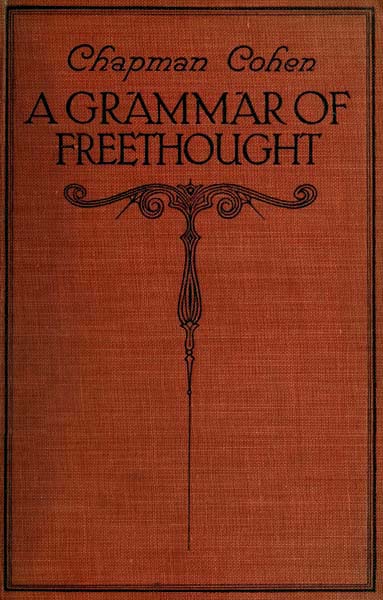

Under Cohen The Freethinker changed. There was less satire and ‘bible bashing’, although Cohen’s comments on religion and the religious were nothing if not caustic. Cohen was a gifted writer with a talent for explaining complicated philosophical ideas and their implications for religion and life to ordinary people. He was also interested in modern science and its implications for religious belief. Although he might not have described himself as a sociologist, he had a talent for understanding and explaining social forces too. His 18 Pamphlets for the People have probably never been bettered as statements of the position of unbelievers. As well as writing much of the 16 foolscap pages of The Freethinker each week, he authored numerous leaflets and pamphlets and more than twenty books.

Cohen was as effective as a lecturer and debater as he was as a writer. Throughout the interwar years, from Autumn until Spring, he travelled the length and breadth of the country at weekends for speaking engagements. When it came to hecklers, he lacked the physical stature of a Bradlaugh but he had the wit and sharp tongue to deal with rowdy opponents. Cohen never gave voice to party political views and during his time as President the NSS moved further away from campaigning on the current political issues. The organisation became increasingly isolated from other radical, campaigning movements.

Cohen’s happy and comfortable family life was marred only by the death of his daughter Daisy at the age of 28 from tuberculosis. It is perhaps no coincidence that his son, Raymond, became a hospital consultant specialising in lung disease.

By 1945 Cohen’s powers were on the wane and his writings had become repetitive. He found it difficult to adapt to a changing world and fashions. Following a stormy NSS Annual Conference he resigned as President of the Society in 1949. Two years later, at the age of 83, he resigned as editor of The Freethinker, a position he had held for 36 years. Unofficially he had been doing the job longer. During a long lifetime he had probably written and lectured more than any other individual ever has.

Chapman Cohen died on 4 February 1954. His successor as editor of The Freethinker, F.A. Ridley, wrote

As the eloquent and acute spokesman of the advanced minority upon whom progress always ultimately depends, Mr Cohen will be long held in honour. His fearless, razor-edged intellect dispelled the dark clouds of superstition wherever it turned its penetrating light.

Cohen is one a of number of secular Jewish people who have exercised significant influence in the development and promotion of secularist and humanist ideals. In his long career as a leading light of the National Secular Society, and a prolific writer on freethought subjects, he was admired as a particularly eloquent voice for rationalism, compassion, and equality.

Alice Woods was an educationist and headteacher; a member of the Hampstead Ethical Institute, and a proponent of moral education. […]

Why not agree to differ about the questions which no one denies to be all but insoluble, and become allies […]

If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, […]

… in broad terms, with our lecturers we attempt to define our intellectual standpoint; with our music we try to […]