It is a principle innate and co-natural to every man to have an insatiable inclination to the truth and to seek for it as for hid treasure. So I proceeded until the more I thought thereon, the further I was from finding the verity I desired…

Thomas Aikenhead

Scottish student and freethinker Thomas Aikenhead was the last person in Great Britain to be executed for blasphemy, sentenced to death by hanging in December 1696. His punishment was designed to be ‘to the example and terror of others to committ the lyke in tyme coming’, and acutely represented the dangers of vocal unbelief in 17th century Britain. Aikenhead’s pursuit of truth by way of reason, his belief in speaking freely, and his sense that both were the natural inheritance of humankind helped pave the way for freethinkers and humanists to come.

Thomas Aikenhead was baptised on 28 March 1676 in Edinburgh. He was the son of James Aikenhead, an apothecary, and Helen Ramsay, whose father had been a minister. Aikenhead was in his third year at the University of Edinburgh when, on 10 November 1696, he was called before the Scottish privy council, accused of blasphemy.

Aikenhead’s accusers took pains to outline the perceived outrageousness and extremity of his proclamations, charging him with ridiculing the Bible, denying the divinity of Jesus Christ, refuting the reality of miracles, and rejecting the doctrine of the Trinity. Aikenhead’s indictment read that he had

repeatedly maintained, in conversation, that theology was a rhapsody of ill-invented nonsense, patched up partly of the moral doctrines of philosophers, and partly of poetical fictions and extravagant chimeras.

He was claimed to have said that

the Holy Scriptures were stuffed with such madness, nonsense, and contradictions, that he admired the stupidity of the world in being so long deluded by them.

The trial took place on 23 December 1696, invoking two Scottish parliamentary acts: one from 1661 making blasphemous utterances punishable by death; the second from 1695 suggesting lesser sentences for two offences, before recommending execution on the third strike. In Aikenhead’s case, the former penalty was imposed, in spite of his pleas for leniency. The brutality of his punishment speaks both to the forthrightness of Aikenhead’s rejection of religious teachings, and to the fear among the privy council and religious authorities of the danger of such ideas.

Thomas Aikenhead’s execution took place on 8 January 1697. He was marched from Edinburgh to Leith, guarded by two lines of fusiliers, and hanged. A paper left by Aikenhead outlined his pursuit of truth through examination and questioning, presenting himself as a thoughtful inquirer rather than a remorseless blasphemer. His examinations of religious doctrine, in the light of his own reason, led him to conclude that ‘God, the world, and nature, are but one thing’ and that ‘the world was from eternity’.

Described as being ‘as complete a freethinker as any in early modern Europe’, Aikenhead’s case forms part of a long history of brutal suppression of unbelief, and made use of blasphemy laws the like of which long outlived him. Aikenhead’s punishment divided opinion in Scotland and England, but its intended aim – to serve as a warning to others – was clearly effective. Philosopher and freethinker John Locke, who read reports of the case in the London newspapers, gathered material associated with the case, his papers comprising the fullest collection of related documents. This fear of legal repercussions and reputational damage led many religious sceptics throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, Locke included, to veil their criticisms of religion and disguise any ideas which could be perceived as atheist. Although this can suggest a general absence of humanist thinking during and before this time, prominent examples like that of Thomas Aikenhead serve to prove its very real presence, making clear the reasons for unbelief to go unexpressed and unrecorded.

Organisations like Humanists UK and Humanists International today continue to fight the brutal punishment of blasphemy throughout the world, and have been instrumental in abolishing blasphemy laws in the UK.

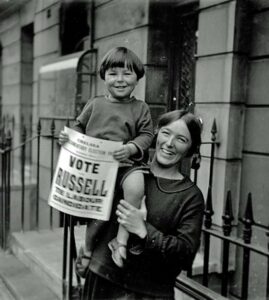

The… women on the early ALRA committee were similar in background and outlook. Most of them were active members of […]

… a man who thinks himself bound to all offices of Humanity. Ephraim Chambers, self-composed epitaph Ephraim Chambers was an […]

I see this kind of love – the empathy that should be common to all living creatures – rather than […]

Indian social and religious reformer Rammohun Roy is sometimes referred to as the ‘father of modern India’: a progressive thinker, […]