Dare to be free.

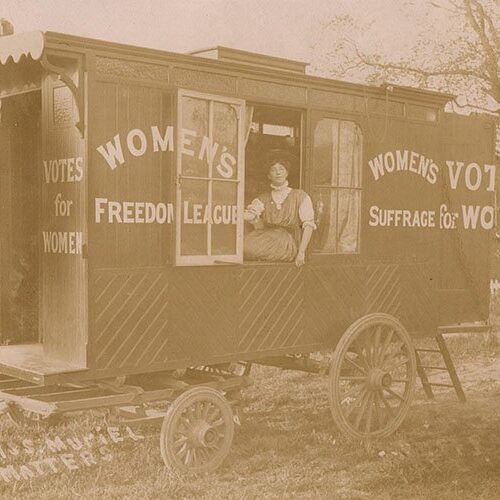

Slogan of the Women’s Freedom League

The Women’s Freedom League (WFL) was a militant suffrage organisation, founded by breakaway members from the more widely known Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Among its key members were many humanists and freethinkers, including members of – and speakers to – the ethical societies. In other ways too, the WFL was closely associated with the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK), including in its founding, which took place at the Emerson Club, on the premises of the Union.

The Women’s Freedom League was formed in 1907 by dissenting members of the WSPU, which had grown increasingly autocratic under the leadership of Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst. This included the rejection of a constitution document drawn up by Teresa Billington-Greig, a socialist and former teacher, who became a founding member of the WFL. All three of the group’s founders, Billington-Greig, Charlotte Despard, and Edith How-Martyn, were freethinkers in religion as well as politics, and a devotion to democracy, dialogue, and cooperation underpinned the early work of the WFL.

As suggested by its name, the Women’s Freedom League envisioned emancipation for women beyond merely gaining the vote. It recognised the wide-reaching disadvantages of a patriarchal society, particularly for working class women, and as such sought sweeping societal reform. In this, the shared sympathies of the ethical societies and WFL in particular are clear. Many women within the early humanist movement combined a rejection of the literal truth of the Bible with new understandings of science, to challenge traditional gender roles and hierarchies, as well as oppressive notions of Christian morality. The writings of the Union’s first chief executive Zona Vallance epitomised this, although she died in 1904 before the WFL came into being. A founding member of the WFL, however, was longtime worker for the Union of Ethical Societies Lillie Boileau.

Though self-defined as militant, the understanding and enactment of this varied over the course of the WFL’s existence, and was interpreted differently among its members and supporters. Its tactics ranged from civil disobedience and public disruption, to attacks on property and window breaking. In efforts to retain an identity and approach distinct from the WSPU, the leadership of the Women’s Freedom League was continually working to establish its own brand of militancy and spectacle, while also retaining the support and unity of its members. It was helped by the many artists, writers, and actors among them, who contributed to the WFL’s attention-grabbing events, publications, and processions.

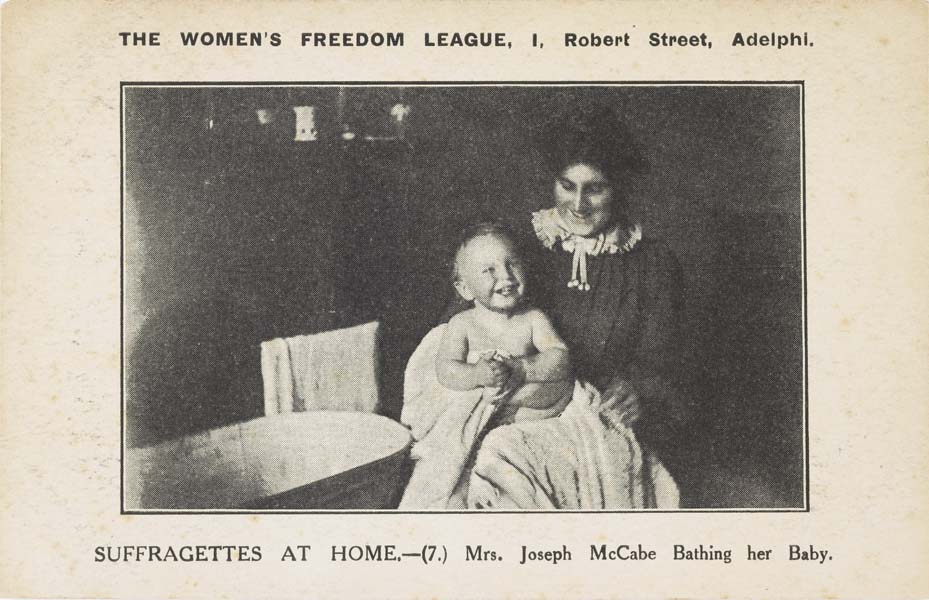

One notable initiative of the Women’s Freedom League was the census boycott of 1911, which encouraged members to refuse to fill in, or to deface, their census sheets. Many did, including a number of women who were also members of the ethical societies. These included lifelong humanist Beatrice McCabe, who listed every member of her household including pets, and West London Ethical Society member Eleanora Maund, whose attempts to write ‘wife away’ were thwarted by her husband. Other forms of civil disobedience were used too, including refusal to pay taxes. Many members – notably Lillie Boileau – were arrested in the course of their activities.

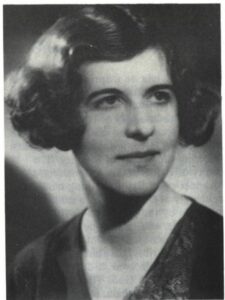

Compared to many of the other suffrage societies, the Women’s Freedom League had an impressively long life. It remained active until 1961, taking part in efforts to achieve fully equal franchise (obtained with the 1928 Representation of the People Act), and latterly to continue working for complete equality in all areas of society. It was dissolved on the death of its final president, Marian Reeves, who had been a part of the League for five decades. Reeves was a devoted feminist, a friend of E.M. Forster, and – according to her friend Kate O’Brien – ‘a walking manifestation of Voltaire’s maxim: “I hate what you are saying, but I will die for your right to say it”.’

The actress turned campaigner and human rights activist Sylvia Scaffardi was a co-founder of The Council of Civil Liberties, along […]

This Society has for its object the promotion of right conduct on a purely natural and human basis and the […]

Throughout his life, Professor of Philosophy, John Muirhead, sought to put his ethical principles into practice. Indeed, whilst philosophers are […]

Elected to Parliament in 1949… and here I am! Where else could I be? The pages of the New Humanist […]